AP Syllabus focus:

‘A city’s infrastructure includes transportation, water, sanitation, energy, and communication systems that support daily life and economic activity.’

Urban infrastructure forms the essential physical and organizational foundation that allows cities to function, shaping daily life, economic opportunity, and spatial development while determining a city’s capacity to grow sustainably.

Understanding What Urban Infrastructure Includes

Urban infrastructure refers to the interconnected systems that enable a city to operate efficiently and support its population. These systems form the backbone of urbanization, influencing patterns of movement, resource distribution, and economic productivity. Infrastructure also acts as a key indicator of development because well-planned networks reduce transaction costs, improve quality of life, and strengthen resilience. Urban geographers study these systems to understand how physical networks shape social and economic outcomes.

Core Categories of Urban Infrastructure

Urban infrastructure can be grouped into several major components, each fulfilling specific urban functions. While they operate independently, they are highly interdependent, meaning the failure or weakness of one system can disrupt others.

Transportation Systems

Transportation infrastructure provides mobility for people, goods, and services across the urban landscape. It determines accessibility, commute patterns, and economic linkages within a metropolitan area.

Key components include:

Road networks such as highways, arterial roads, and local streets that support private vehicles, freight, and public buses.

Public transit systems including subways, buses, light rail, and commuter trains that reduce congestion and connect residential areas to employment centers.

Airports and seaports that make global and regional trade possible by facilitating the movement of goods and travelers.

Accessibility: The ease with which people or goods can reach desired destinations, influenced by travel time, cost, and network efficiency.

Transportation networks strongly influence urban spatial structure, often shaping where businesses locate and how neighborhoods develop. For example, major highways can encourage suburbanization by providing faster access between central cities and peripheral areas. These systems are highly interdependent; a disruption in one network often affects others, which is why planners think about infrastructure as a connected system rather than isolated parts.

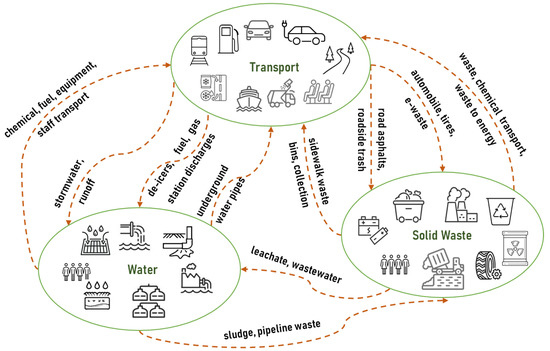

This diagram illustrates interdependencies among urban transport, water, and solid waste systems using labeled icons and directional arrows. It highlights how flows such as stormwater, fuel, and waste link multiple types of infrastructure. The image includes more detail on solid waste than the syllabus requires but effectively shows how sanitation fits within the broader infrastructure network. Source.

Water Systems

Water infrastructure ensures reliable access to clean water—a critical prerequisite for public health and urban growth. These systems include:

Water supply networks that extract, treat, and distribute potable water to households and businesses.

Reservoirs and aqueducts that store and transport water across long distances, especially for cities located in arid regions.

Stormwater systems such as drains, culverts, and retention basins that minimize flooding and protect property.

Water-supply infrastructure includes reservoirs or wells, treatment plants, and pipe networks that deliver safe drinking water to households and businesses.

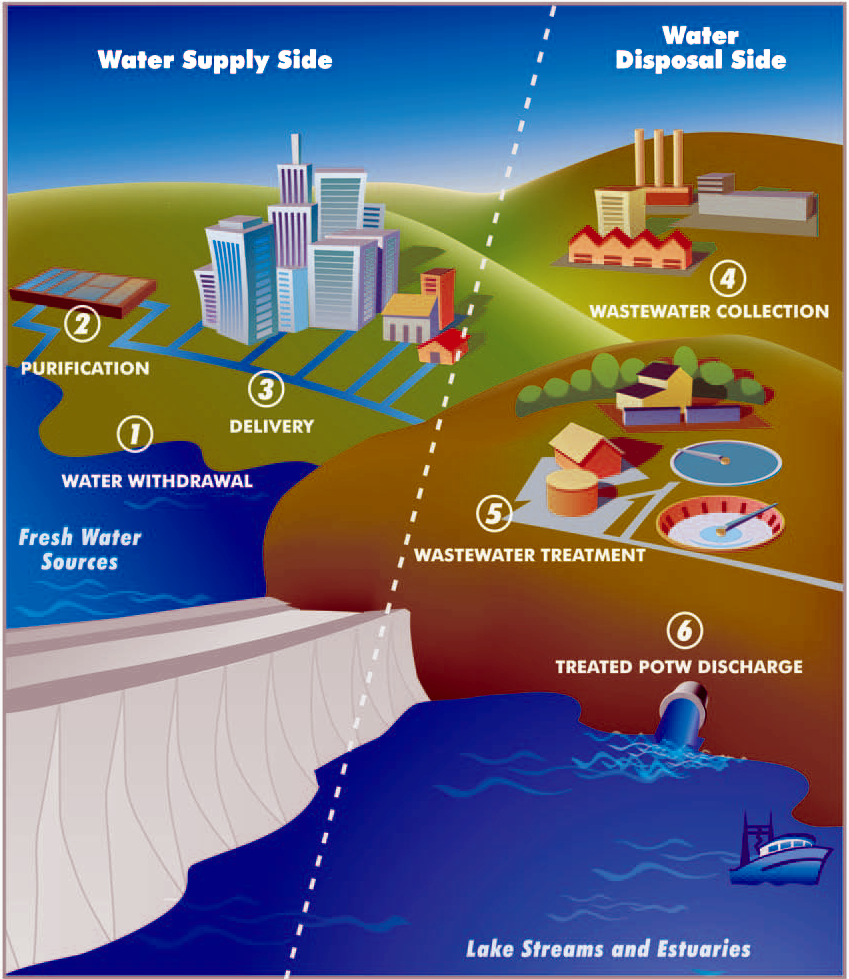

This illustration depicts a typical urban water cycle, including drinking-water intake, treatment, storage, distribution, sewage collection, and wastewater treatment. It clarifies how potable water systems connect with sewer networks and stormwater pathways. The diagram includes additional natural hydrologic details not required by the syllabus, but they help contextualize water and sanitation systems within the broader environment. Source.

Potable Water: Water that is safe for human consumption, meeting health and safety standards for contaminants.

Water systems must be constantly maintained because leaks, contamination, or shortages can affect millions of urban residents. These infrastructures also reflect inequalities, as access varies across neighborhoods based on investment and governance.

Sanitation and Waste Management

Sanitation systems protect environmental and human health by removing and treating waste. In rapidly growing cities, the strain on sanitation infrastructure is one of the most visible challenges of urbanization.

Key sanitation components include:

Sewer networks that transport wastewater to treatment facilities.

Wastewater treatment plants that remove pollutants before water is released back into rivers or oceans.

Solid waste systems that collect, recycle, and dispose of household and industrial waste.

Improper sanitation can lead to disease outbreaks, degraded urban environments, and long-term ecological damage. Cities in the periphery and semiperiphery often struggle with informal or insufficient sanitation systems, contributing to uneven development.

Energy Infrastructure

Energy systems provide the power needed for residential, industrial, and commercial activities. A stable supply enables economic growth and supports modern lifestyles.

Energy infrastructure includes:

Electrical grids that generate, transmit, and distribute electricity.

Power plants using resources such as coal, natural gas, hydroelectricity, solar, or wind.

Fuel distribution networks supplying gas and petroleum for transportation and heating.

Grid Reliability: The ability of an electrical system to deliver uninterrupted power despite fluctuations in demand or failures in equipment.

Energy systems are often spatially uneven, with some neighborhoods experiencing outages or limited access due to aging infrastructure or underinvestment.

Communication Networks

Communication infrastructure supports the flow of information, enabling economic activity, education, and governance. Modern cities rely heavily on these interconnected digital and physical networks.

Key communication components include:

Wired networks such as fiber-optic and cable systems that provide internet and phone services.

Wireless networks including cellular towers and satellite links supporting mobile communication.

Broadcast infrastructure that transmits television and radio signals.

These networks link cities to global systems of trade and information, reinforcing their position in the urban hierarchy. High-quality communication infrastructure is essential for advanced services, business operations, and civic participation.

Interdependence of Infrastructure Systems

Urban infrastructure functions as a complex system where each component depends on others to operate effectively. For example:

Transportation requires energy for vehicle operation and lighting.

Water treatment facilities need electricity and communication systems to coordinate distribution.

Communication networks require stable power supplies to maintain connectivity.

Many of these facilities are underground, especially pipes and cables, which must share limited space beneath streets and sidewalks.

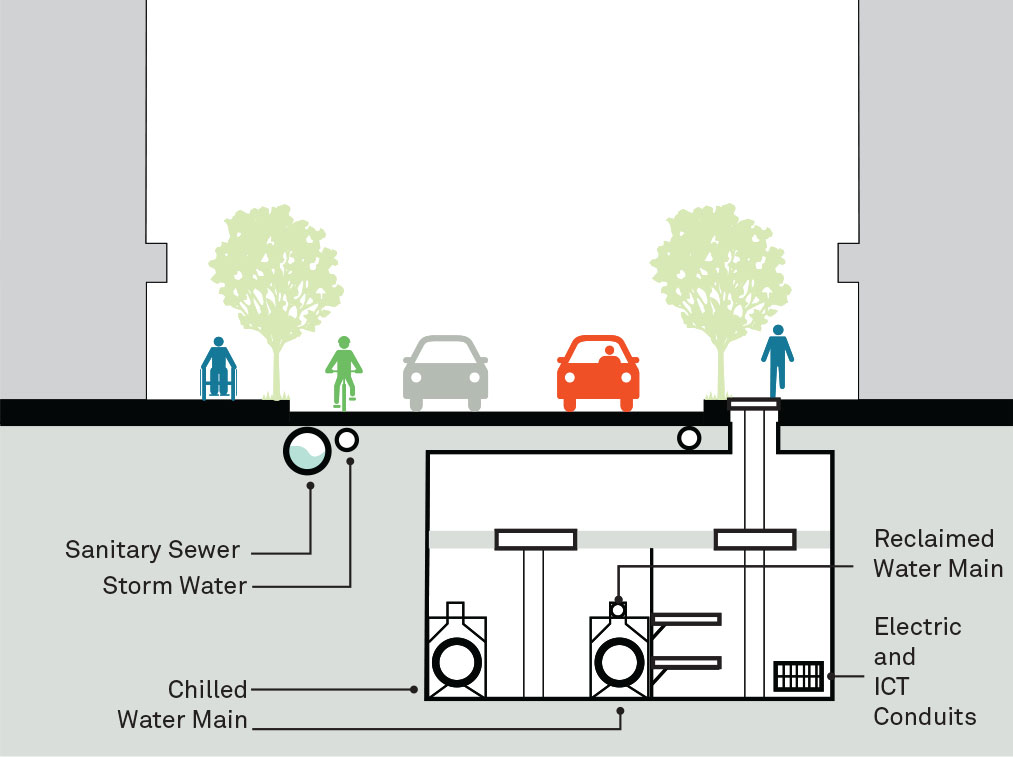

This cross-section shows how sanitary sewer, stormwater, water, electric, and ICT lines can be co-located in a single underground utilities corridor. It illustrates how multiple infrastructure systems share constrained subsurface space beneath streets. Extra details, such as chilled water lines, extend slightly beyond the syllabus but help depict real-world utility configurations. Source.

This interdependence means disruptions—such as power failures, aging pipes, or damaged roads—can cascade across the urban system. Urban planners must account for these relationships to ensure redundancy and resilience.

Infrastructure and Daily Urban Life

Infrastructure shapes almost every aspect of daily life, from commuting and communication to hygiene and energy consumption. These systems support economic activity by enabling firms and workers to function efficiently. They also influence social equity because uneven infrastructure investment can create disparities in health, access, and opportunity. Understanding what urban infrastructure includes provides a foundation for analyzing how cities grow, compete, and respond to change.

FAQ

Cities typically use spatial planning tools, including land-use maps, population projections, and engineering assessments, to determine where infrastructure should be installed.

Decisions often depend on:

Demand from new housing or commercial development

Safety regulations and environmental constraints

The cost and feasibility of construction

The ability to connect with existing networks

Infrastructure placement also reflects political priorities, which can influence which neighbourhoods receive upgrades first.

Ageing pipes, cables, and transport systems often operate beyond their intended lifespan, leading to leaks, power failures, or service disruptions.

Older infrastructure is harder and more expensive to repair because:

Replacement requires digging up streets or disrupting traffic

Materials and designs may no longer meet modern standards

Systems built decades ago were not designed to support current population sizes

These challenges create a backlog of maintenance that many cities struggle to fund.

Communication networks—especially digital systems—coordinate the operation of other infrastructure.

Examples include:

Real-time data for traffic signals, improving transport flow

Automated monitoring of water pressure or leakage

Smart grids that adjust electricity distribution based on demand

These systems reduce energy waste, improve safety, and help authorities respond quickly to breakdowns.

Infrastructure costs vary widely depending on materials, scale, local geography, and labour requirements.

Key cost drivers include:

Whether infrastructure is above or below ground

Distance from water sources, power plants, or fibre-optic nodes

The need to retrofit old networks rather than build new ones

Local climate, which affects durability and maintenance schedules

Dense cities often face higher costs due to limited construction space.

Climate influences what materials and designs are suitable for long-term functionality.

For example:

Cities in hot climates may require heat-resistant road surfaces or insulated cables

Coastal cities need drainage systems that cope with heavy rainfall and storm surges

Areas prone to freezing require deeper water pipes to prevent bursting

Infrastructure planning must anticipate long-term climate trends, not just present conditions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain one way in which urban water infrastructure supports daily urban life.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a correct function of urban water infrastructure (e.g., providing potable water, enabling sanitation, supporting public health).

1 mark for explaining how this function supports daily life (e.g., access to safe drinking water prevents disease; water supply enables household tasks and commercial activity).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Using an urban area you have studied or a general example, explain how different types of urban infrastructure are interdependent. Refer to at least two types of infrastructure in your answer.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least two types of urban infrastructure (e.g., transport, energy, water, sanitation, communication).

1 mark for explaining how the first infrastructure type depends on another (e.g., transport systems require energy for lighting, signals, and operations).

1 mark for explaining how the second infrastructure type depends on another (e.g., water treatment facilities need electricity to operate pumps).

1 mark for providing a clear example that illustrates interdependence (e.g., a blackout causing disruptions to water supply or transit).

1 mark for demonstrating understanding of the wider implications of interdependence (e.g., cascading failures, resilience planning, coordinated infrastructure investment).