AP Syllabus focus:

‘Access to health care and literacy rates are social measures used to compare quality of life and human well-being.’

Health and education indicators help geographers assess human well-being by showing how access to medical services and literacy levels shape development patterns, opportunities, and spatial inequalities worldwide.

Access to Health Care and Literacy as Social Development Indicators

Health and education are core dimensions of human development because they reflect how effectively a society invests in its population’s well-being. Access to health care refers to the ability of people to obtain necessary medical services, while literacy represents the capacity to read and write at a basic level. These indicators reveal disparities within and among states and help explain uneven development outcomes.

Why Social Indicators Matter in AP Human Geography

Social indicators provide insight that economic indicators alone cannot capture. Two places with similar income levels may differ greatly in health outcomes or educational access. By examining access to health care and literacy rates, geographers identify how infrastructure, government policy, and social norms shape daily life and opportunities.

Access to Health Care

Access to health care varies widely across regions due to differences in infrastructure, government investment, and socioeconomic conditions. This indicator reflects not only the presence of facilities but also their affordability, quality, and cultural accessibility.

Primary health care is the first point of contact people have with the medical system and often determines long-term health outcomes.

Primary Health Care: Basic medical services including prevention, treatment of common illnesses, and maternal-child health support.

Countries with strong primary health systems tend to experience lower mortality rates, better disease prevention, and improved life expectancy. This demonstrates the strong link between health access and broader development patterns.

Access to health care involves multiple components that geographers analyze:

Availability: Number and distribution of hospitals, clinics, and trained medical professionals.

Accessibility: Physical or geographic ease of reaching medical services, often influenced by transportation networks.

Affordability: Whether populations can pay for services, shaped by insurance systems and income levels.

Acceptability: Cultural compatibility between providers and patients, including gender norms and language barriers.

Quality: The reliability, safety, and effectiveness of medical services.

Spatial Patterns of Health Access

Geographers observe significant core–periphery differences in health care distribution:

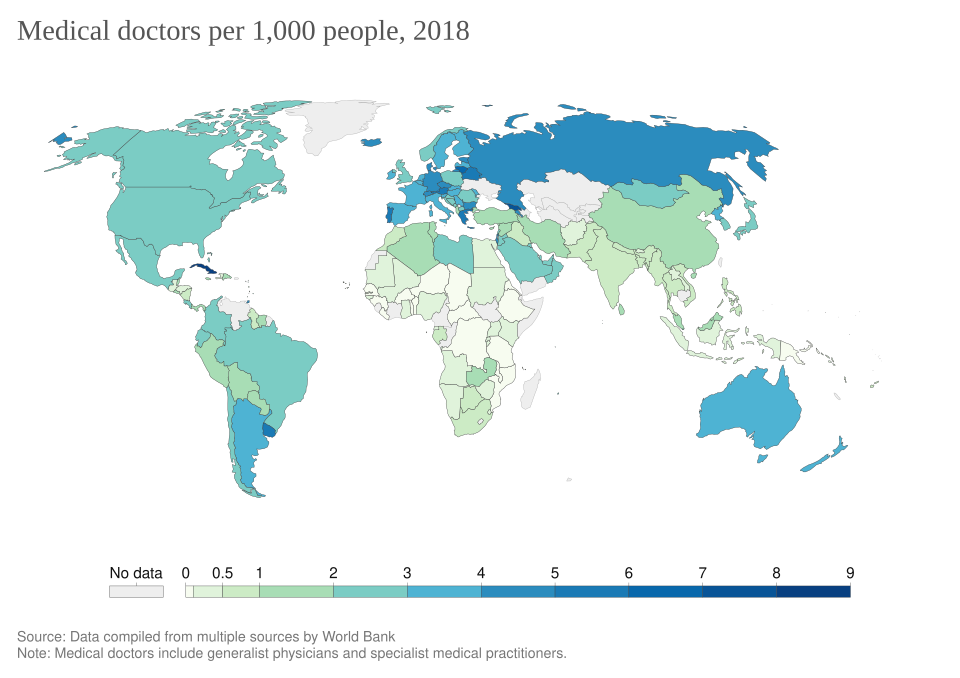

World map showing countries shaded by the number of medical doctors per 1,000 people, with darker shades representing higher doctor density. The map illustrates spatial inequalities in physician availability, highlighting disparities between core and peripheral regions. The precise 2018 values and full legend exceed syllabus requirements but reinforce the concept of health-care access as a development indicator. Source.

Core states often have dense medical networks, better funding, and advanced technologies.

Many periphery and some semiperiphery states face shortages of doctors, limited rural services, and aging or inadequate infrastructure.

Within countries, urban areas typically enjoy better access than rural, remote, or marginalized regions.

These disparities contribute to uneven health outcomes such as varying infant mortality rates and life expectancies.

Education and Literacy

Literacy is a foundational indicator of educational attainment and human capital. It enables people to participate fully in economic and civic life and strongly correlates with employment opportunities, income levels, and social empowerment.

Literacy Rate: The percentage of people in a population who can read and write at a basic functional level.

A wide sentence is needed here to maintain spacing before any other block and to connect literacy to broader development outcomes in a coherent way that supports geographic analysis.

Gender differences in literacy offer especially important insight. In some regions, girls face barriers such as school fees, household labor expectations, or safety concerns. These obstacles limit female participation in education and reinforce structural inequalities.

Components Shaping Literacy Outcomes

Literacy patterns result from the interaction of several factors:

School infrastructure: Adequate buildings, electricity, sanitation, and classroom resources.

Teacher training and staffing: Availability of well-prepared instructors and manageable class sizes.

Economic stability: Families with constrained resources may keep children out of school to work.

Government policy: Investment in compulsory education and adult literacy programs.

Cultural and gender norms: Societal expectations that influence who is encouraged or permitted to attend school.

Spatial Patterns of Literacy

Geographers identify clear global trends related to literacy:

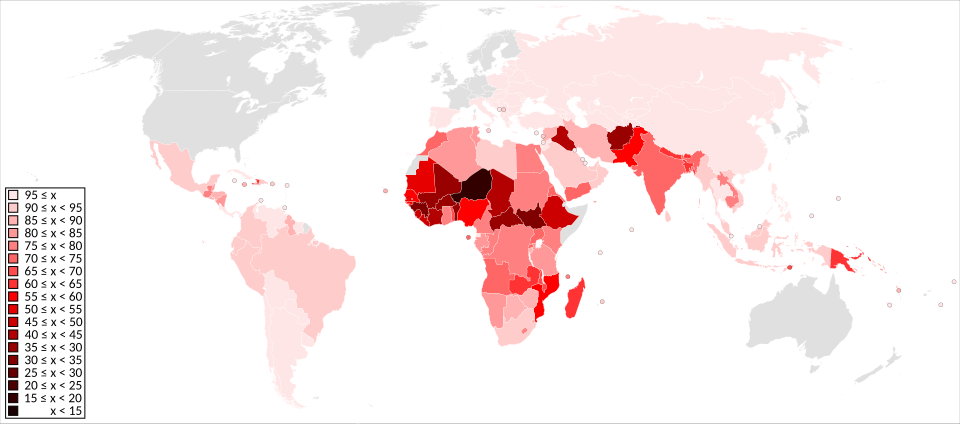

World map illustrating literacy rates by country, with darker shades representing higher national literacy levels. The map highlights major spatial patterns in educational attainment, including strong regional contrasts between core and peripheral areas. The exact numerical ranges and legend exceed syllabus needs but deepen understanding of literacy as a development indicator. Source.

Core regions typically show near-universal literacy due to compulsory schooling and strong educational funding.

Semiperiphery states vary widely, with rapid improvement in some (e.g., emerging industrial economies) and persistent challenges in others.

Periphery regions often face lower literacy levels, particularly among women and rural populations, due to limited infrastructure and social inequalities.

These spatial patterns reveal how education mirrors broader development divides and often reproduces them across generations.

Linking Health Access and Literacy to Development

Health and education indicators are deeply interconnected. Literacy improves health outcomes by enabling individuals to read medication instructions, understand health information, and access employment that provides insurance or stable income. Meanwhile, good health supports school attendance and cognitive development.

Geographers analyze these indicators together because:

They reflect quality of life, one of the central concerns of human development.

They measure human capital, influencing a region’s economic productivity.

They help explain spatial inequality, showing how investment—or lack of it—shapes geographic patterns of opportunity.

Understanding access to health care and literacy allows AP Human Geography students to evaluate development not only through economic statistics but also through lived human experiences that define well-being across different places.

FAQ

Cultural norms can shape whether individuals seek medical care, the types of providers they trust, and the treatments they consider acceptable.

In some societies, traditional healers are preferred over formal medical systems, which can delay treatment.

Gender norms may restrict women’s mobility or decision-making power, limiting their ability to access clinics independently.

Language barriers can also discourage people from visiting health facilities if providers do not speak local or minority languages.

Raising literacy levels strengthens human capital and expands the skilled workforce.

It supports economic diversification, allowing countries to shift towards higher-value sectors.

Improved literacy also enhances civic participation, enabling citizens to engage with public services, understand rights, and hold governments accountable.

Governments may prioritise adult literacy programmes in regions with persistent educational disadvantages to reduce long-term inequality.

Key infrastructure extends beyond hospitals and clinics.

Reliable road networks that connect remote settlements to health facilities

Transport options such as buses or community ambulances

Electricity and clean water systems that ensure safe medical environments

Digital connectivity that supports telemedicine, appointment management, and health education

These improvements collectively reduce travel time and widen access to essential services.

Higher literacy levels, especially among women, tend to correlate with shifts in demographic behaviour.

Educated individuals are more likely to access information about family planning and child health, contributing to lower fertility rates.

Literacy can also encourage delayed marriage and greater workforce participation, which influences population structure over time.

These demographic effects vary by region depending on economic conditions, cultural expectations, and government policy.

Urban growth often outpaces the capacity of public services.

New informal settlements may lack clinics, schools, sanitation, and transport links.

Rapidly increasing populations strain existing facilities, leading to overcrowded classrooms and long waiting times at clinics.

Governments must coordinate land-use planning, infrastructure expansion, and social programmes to meet the needs of diverse and expanding urban populations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which limited access to health care can hinder a country’s social development.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid impact (e.g., higher infant mortality, increased disease burden, reduced life expectancy).

1 mark for explaining how this impact affects social development (e.g., poorer health reduces workforce productivity).

1 mark for linking the consequence to broader well-being or quality of life (e.g., communities experience long-term inequality as preventable illnesses persist).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how variations in literacy rates can contribute to spatial inequalities within a country.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that literacy rates vary spatially (e.g., urban vs rural, gender differences).

1 mark for explaining how low literacy can limit access to skilled employment.

1 mark for explaining how high literacy can enhance economic opportunities and mobility.

1 mark for linking literacy disparities to uneven development or human capital differences.

1 mark for providing a relevant example (named country, region, or social group).

1 mark for overall analytical depth showing how literacy gaps reinforce spatial inequality patterns.