AP Syllabus focus:

‘Sustainability principles explain how industrialization shapes places and how planning can balance development with environmental limits.’

Industrialization reshapes landscapes, resource use, and settlement patterns, making sustainability principles essential for guiding future development. Spatial planning seeks to balance growth, environmental limits, and human well-being.

Sustainability Principles and Spatial Development

Sustainability in AP Human Geography refers to meeting present needs without undermining the ability of future generations to meet theirs. This idea connects directly to how industrialization transforms spatial patterns of land use, transportation, and resource extraction.

The Three Pillars of Sustainability

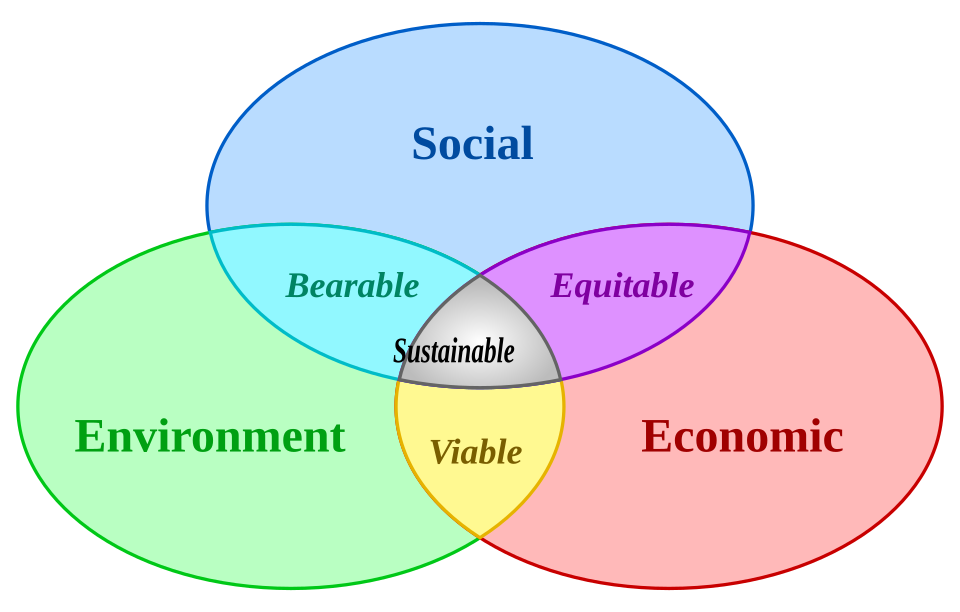

The widely used framework of the three pillars of sustainability—environmental, economic, and social—helps geographers evaluate how development occurs across space.

This diagram shows the three main dimensions of sustainability: environment, society, and economy. The central overlap illustrates that sustainable development requires all three dimensions to be satisfied simultaneously. The diagram includes additional labels beyond the AP syllabus, but it effectively visualizes how sustainability integrates multiple goals. Source.

Environmental sustainability focuses on protecting ecological systems and natural resources so landscapes can support long-term human activity.

Economic sustainability requires stable and efficient economic systems that avoid overuse of finite resources.

Social sustainability emphasizes equity, safety, and quality of life within and among communities.

When applied to spatial development, these pillars guide decisions about where industries locate, how cities expand, and which regions receive investment.

Environmental Limits and Industrialization

Industrialization sharply increases energy use, resource extraction, and waste production. Spatial planners address environmental limits by regulating land use patterns and promoting greener urban forms.

Environmental Limits: The ecological boundaries within which human development must operate to avoid long-term environmental damage.

Planners integrate these limits by:

Directing industrial sites away from sensitive habitats

Establishing greenbelts to manage urban expansion

Promoting mixed-use, compact development to reduce land consumption

These strategies help align industrial growth with ecological capacity.

Spatial Organization and Land-Use Planning

Industrialization reshapes settlement patterns, concentrating economic activity in cities and along transportation corridors. Spatial development planning organizes these changes to ensure efficient and sustainable land use.

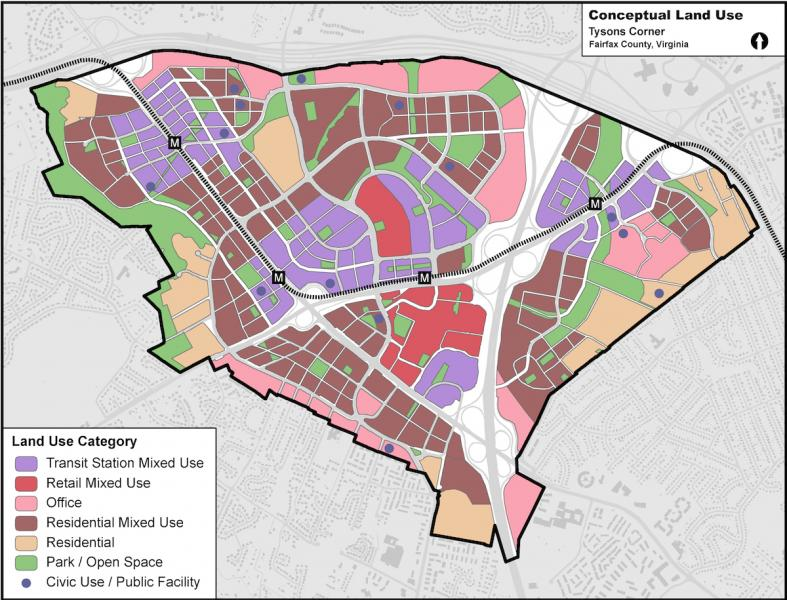

Key planning tools include:

Zoning to separate harmful industrial uses from residential areas

Transportation planning to reduce congestion and emissions

Urban growth boundaries to prevent sprawl

Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) to evaluate development proposals

These tools help coordinate growth and protect communities from environmental burdens.

Zoning maps and comprehensive plans visualize where industrial expansion, housing, greenbelts, and transportation corridors should go.

This map illustrates how planners assign different zones for residential, mixed-use, transit-oriented, and open-space functions. The layout shows how spatial planning shapes density and transportation access while conserving green space. The map contains local details beyond the AP syllabus, but it effectively demonstrates how zoning supports sustainable development. Source.

Urban Form, Density, and Sustainability

Cities built during industrialization often spread outward, creating low-density sprawl that increases resource consumption. Sustainable planning promotes compact urban form, higher densities, and transit-oriented development to reduce ecological footprints.

Ecological Footprint: The amount of land and resources required to support a population’s consumption and waste.

Planners use this measure to compare the sustainability of different spatial patterns. Dense, walkable neighborhoods typically have smaller ecological footprints than dispersed suburban landscapes.

A balanced approach also addresses equity by ensuring access to transportation, services, and green space across neighborhoods.

Energy Use, Infrastructure, and Spatial Patterns

Industrialization historically relied on fossil-fuel-based infrastructure, shaping spatial patterns of factories, power plants, and transportation networks. Sustainable development promotes transitions toward:

Renewable energy installations located near consumption areas

Electrified public transportation systems

Energy-efficient industrial parks

Green building standards in urban centers

These shifts influence where new industries and populations concentrate, altering traditional industrial geographies.

Resilience and Climate-Responsive Planning

Sustainable spatial development increasingly incorporates resilience, defined as the ability of places to withstand and adapt to environmental shocks such as floods, droughts, and heat waves.

Resilience: The capacity of a place or system to absorb disturbances while maintaining essential functions.

Planners enhance resilience through:

Flood-resistant zoning

Coastal setback zones in areas threatened by sea-level rise

Heat-mitigation designs such as urban tree canopies

Diversified economic bases that reduce dependence on single industries

These strategies help communities adapt to climate-related risks connected to industrial and urban development.

Sustainable Transportation and Spatial Connectivity

Transportation is central to industrialization and shapes spatial development by linking factories, labor, and markets. Sustainable planning emphasizes:

Efficient public transit networks

Freight systems that minimize emissions

Walkable and bike-friendly street layouts

Strategic placement of logistics hubs to lower transport distances

Improved connectivity supports economic activity while reducing environmental pressures.

Balancing Development and Environmental Limits

Spatial planning ultimately seeks a balance between promoting industrial and economic development and respecting ecological limits. This aligns directly with the AP syllabus requirement that sustainability principles explain how industrialization shapes places and how planning can balance development with environmental limits.

To manage this balance, planners integrate sustainability goals into regional and urban strategies through:

Long-range comprehensive planning

Cross-regional coordination of transportation and land use

Environmental zoning overlays

Policies encouraging green industrial innovation

These approaches illustrate how sustainability principles guide spatial decision-making and help create environments that support both development and long-term ecological health.

FAQ

Mixed-use development reduces the need for long-distance travel by placing homes, jobs, and services close together.

This supports sustainability by:

Lowering transport emissions

Encouraging walking and cycling

Reducing pressure for outward urban expansion

Climate risk mapping identifies areas vulnerable to hazards such as flooding, heat waves, or coastal erosion. Planners use these maps to steer development away from high-risk zones.

This can involve:

Redirecting growth to safer areas

Implementing building codes that address specific risks

Creating buffers such as wetlands or tree canopies

By integrating risk data, cities build resilience while guiding sustainable spatial patterns.

Planners use long-term monitoring frameworks that track changes in land use, transport behaviour, air quality, and ecological indicators.

These frameworks often include:

Periodic environmental impact reviews

Evaluations of infrastructure efficiency

Surveys of residents’ accessibility to services

By comparing these measures against sustainability targets, planners can adjust policies to reduce negative impacts and reinforce positive trends.

Public participation helps ensure that development reflects the needs and priorities of local communities. It also improves legitimacy and long-term compliance.

Participation may involve:

Community workshops

Online consultations

Citizen advisory committees

These processes allow planners to incorporate local knowledge about environmental risks, cultural landscapes, and neighbourhood needs.

Cities protect biodiversity by mapping ecological assets and incorporating these into land-use decisions.

Common approaches include:

Establishing ecological corridors that connect habitats

Restricting development in areas of high conservation value

Replacing lost habitats through green roofs, tree planting, and restored wetlands

These strategies help maintain ecosystem services while allowing urban growth.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which spatial planning can support environmental sustainability in rapidly industrialising urban areas.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid spatial planning strategy (e.g., greenbelts, zoning, compact development).

1 mark for describing how the strategy operates in practice (e.g., limiting sprawl, separating polluting industries from housing).

1 mark for linking the strategy to improved environmental sustainability (e.g., reduced land consumption, lower emissions, protection of habitats).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how sustainability principles influence decisions about the spatial development of urban regions.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for defining or clearly stating a sustainability principle (e.g., environmental limits, social equity, economic viability).

1 mark for identifying how these principles shape spatial decisions (e.g., compact urban form, transport planning).

1 mark for explaining how environmental sustainability affects land-use choices (e.g., avoiding ecologically sensitive zones).

1 mark for explaining how social sustainability influences spatial development (e.g., equitable access to services).

1 mark for explaining how economic sustainability shapes patterns of development (e.g., efficient resource use, supporting long-term economic growth).

1 mark for using at least one relevant example that strengthens the analysis (e.g., a city implementing transit-oriented development or growth boundaries).