AP Syllabus focus:

“Sustainable development addresses the impacts of climate change by promoting cleaner energy and resilient planning.”

Climate change reshapes environmental and economic systems, and sustainable development responses focus on integrating cleaner energy, adaptive planning, and long-term resilience to support equitable, low-impact human well-being.

Climate Change as a Development Challenge

Climate change creates spatially uneven risks that interact directly with economic development. Rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme events disrupt agriculture, infrastructure, and settlement patterns. These impacts influence where people can live, how economies function, and what types of industries can thrive. Sustainable development responses attempt to balance economic growth with environmental protection while planning for long-term climate stability.

Key Concepts for Understanding Climate–Development Interactions

Climate change pressures include physical, social, and economic dimensions. Human activities such as reliance on fossil fuels intensify greenhouse gas emissions, reinforcing warming trends and heightening the urgency for sustainable responses. Meanwhile, low-income regions face disproportionate climate impacts because they often lack robust protective infrastructure, diversified economies, or resources for adaptation.

Greenhouse Gases (GHGs): Gases such as carbon dioxide and methane that trap heat in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

Climate vulnerability differs across places, making resilient planning a central strategy for sustainable development. Resilience refers to the capacity of a system to absorb disturbances, reorganize, and continue functioning.

Sustainable Development Responses to Climate Change

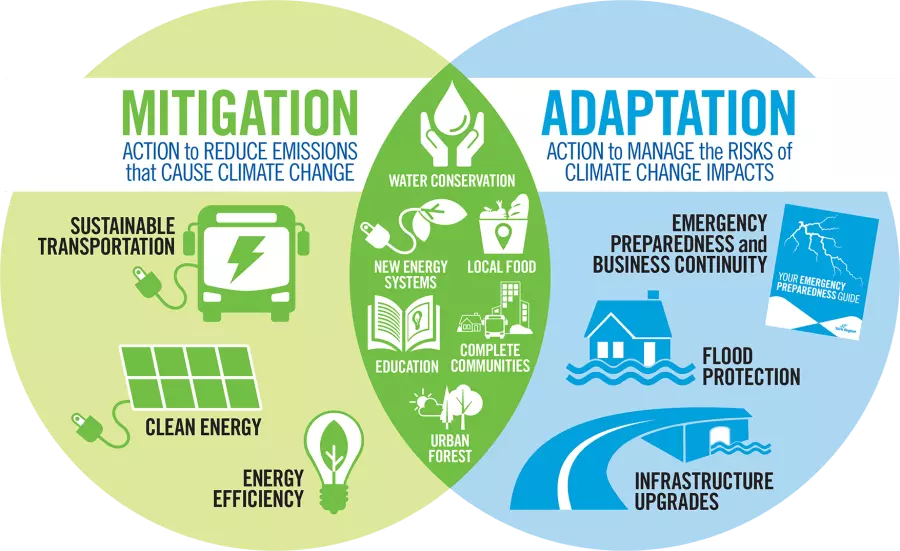

Sustainable development seeks to address climate impacts through mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation limits future warming, while adaptation prepares communities for unavoidable effects. Both approaches shape economic and spatial planning decisions at local, national, and global scales.

This Venn diagram compares climate mitigation actions, which reduce emissions, with adaptation strategies designed to manage climate risks. The overlap highlights shared measures such as water conservation and urban forests that improve resilience. Some examples shown extend beyond the syllabus but illustrate the broader principles of sustainable development responses to climate change. Source.

Mitigation Strategies: Reducing Emissions

Mitigation strategies aim to reduce greenhouse gas outputs and shift economies toward cleaner energy systems

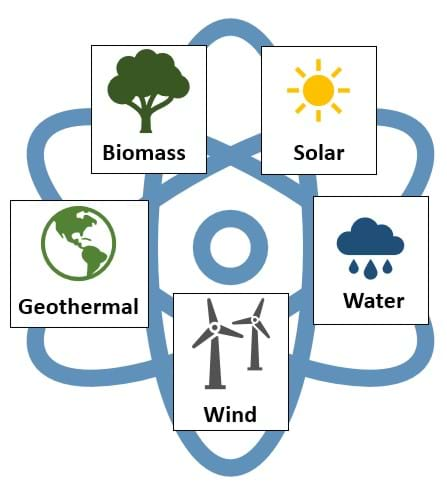

This diagram shows five major renewable energy sources that can replace fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These technologies support sustainable development and vary geographically based on local resource availability. The image includes more specific categories than required by the syllabus but aligns with the broader concept of cleaner energy. Source.

These strategies involve altering production, consumption, and transportation patterns.

Expanding renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, geothermal, and hydropower to replace fossil-fuel-intensive systems.

Implementing energy-efficiency improvements in buildings, transportation networks, and industrial processes to reduce overall energy consumption.

Encouraging compact urban design that reduces car dependency and favors low-emission mobility options.

Supporting reforestation and land-use practices that increase carbon sequestration in vegetation and soils.

Renewable energy development influences spatial patterns. Wind farms, solar arrays, and hydroelectric facilities require specific geographic conditions, creating new economic landscapes and employment opportunities in regions with favorable natural resources.

Adaptation Strategies: Building Resilience

Adaptation addresses the consequences of climate change that cannot be prevented through mitigation alone. Resilient planning is essential for communities exposed to sea-level rise, heat waves, drought, or stronger storms.

Constructing climate-resilient infrastructure such as elevated roads, storm-resistant buildings, and improved drainage systems.

Developing disaster-risk-reduction plans that coordinate emergency responses and community preparedness.

Promoting climate-smart agriculture, including drought-tolerant crops and efficient irrigation systems, to stabilize food supplies.

Relocating populations from high-risk coastal or flood-prone areas when protective measures are insufficient.

Adaptation also requires social strategies such as strengthening healthcare systems, improving public education on climate risks, and ensuring that vulnerable populations receive targeted support.

Cleaner Energy and Spatial Development

The shift toward cleaner energy reshapes global economic geography. Renewable energy investments create new industrial hubs, supply chains, and labor markets. Countries with abundant sunlight, wind corridors, or geothermal reserves gain comparative advantages in energy production.

Energy Transition and Economic Transformation

The transition requires large-scale infrastructure development, from national grids that support variable electricity supplies to local microgrids for rural areas. As economies move away from fossil fuels, traditional coal or oil-producing regions may experience economic decline unless supported by diversification strategies.

Energy Transition: The long-term shift from fossil-fuel-based systems to renewable and low-carbon energy sources.

The spatial distribution of renewable resources influences regional planning. For example, solar energy development often concentrates in arid or semi-arid regions, while wind infrastructure clusters in coastal zones or highland areas. These patterns reinforce the importance of integrating climate considerations into national development strategies.

Resilient Planning and Long-Term Development

Resilient planning integrates climate projections into decisions about housing, infrastructure, and economic development.

This approach helps ensure communities remain functional even as environmental conditions shift.

Planning Tools for Resilience

Planners use vulnerability assessments, environmental impact studies, and zoning strategies to guide development away from high-risk areas.

Updating building codes to withstand extreme weather.

Designing green infrastructure—such as wetlands, permeable surfaces, and urban forests—that buffers against flooding and heat.

Strengthening transportation networks to maintain mobility during climate disruptions.

Resilient planning emphasizes long-term sustainability by ensuring development does not worsen future climate risks or exceed ecological limits.

International Cooperation and Policy Frameworks

Because climate change affects all regions, effective sustainable development responses require multiscale governance. International agreements encourage countries to reduce emissions, share technology, and support adaptation in lower-income regions.

Global Commitments and Local Action

National policies align with global goals but must be implemented locally. City governments often lead in climate innovation through clean-energy initiatives, green-building programs, and community-based adaptation projects. Collaboration among governments, private sectors, and civil society strengthens the overall capacity to respond to climate impacts.

Sustainable development responses reflect the need to harmonize economic growth, environmental protection, and social well-being, ensuring that communities can thrive in the face of a changing global climate.

FAQ

International agreements provide frameworks, funding, and shared targets that encourage national governments to prioritise climate actions.

Local authorities benefit through:

• Access to climate finance for adaptation projects

• Technical guidance on mitigation strategies

• Collaborative networks for sharing best practices

• Policy alignment that supports long-term planning stability

Although implementation occurs locally, international commitments help ensure sustained political and financial support for climate resilience initiatives.

Coastal regions face risks such as sea-level rise, storm surges, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion, requiring adaptation measures like sea walls, managed retreat, and resilient port infrastructure.

Inland regions more commonly experience heatwaves, drought, and altered river flows, which demand different strategies including water-management planning, heat-resilient infrastructure, and land-use adjustments.

Understanding these spatial differences ensures that sustainable development planning aligns with the specific environmental pressures each region faces.

Renewable resources such as solar and wind produce variable outputs that do not always match demand. Energy storage systems help balance this mismatch.

Technologies including batteries, pumped hydro, and thermal-storage facilities allow communities to stabilise supply, reduce reliance on fossil-fuel backups, and increase the viability of renewables at larger scales.

Without adequate storage, regions may struggle to integrate renewable energy into grids, limiting long-term mitigation efforts.

Implementation depends on a combination of governance capacity, financial resources, local knowledge, and public engagement.

Key factors include:

• Availability of funding for infrastructure upgrades or green-infrastructure projects

• Technical expertise to interpret climate projections

• Strong coordination between local authorities, planners, and emergency responders

• Public support for zoning restrictions or relocation efforts

Communities lacking these resources often struggle to adopt long-term climate resilience strategies.

Climate-smart agriculture improves resilience while also contributing to reduced emissions, making it a dual-purpose strategy.

Adaptation benefits include:

• Greater tolerance to drought and heat

• Stabilised yields during climate variability

• Improved water efficiency

Mitigation benefits include:

• Enhanced soil carbon storage

• Reduced fertiliser emissions

• Opportunities for low-emission livestock systems

These combined effects strengthen sustainable development pathways for rural economies.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which sustainable development responses help reduce the impacts of climate change on urban areas.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid sustainable development response (e.g., green infrastructure, clean energy, resilient planning).

• 1 mark for describing how it operates (e.g., reduces emissions, manages runoff, lowers heat).

• 1 mark for explaining its effect on reducing climate impacts in urban areas (e.g., less flooding, reduced heat island effect, improved resilience).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how both mitigation and adaptation strategies contribute to sustainable development in regions vulnerable to climate change.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for defining or clearly describing mitigation.

• 1 mark for defining or clearly describing adaptation.

• 1 mark for explaining how mitigation contributes to sustainable development (e.g., cleaner energy, reduced emissions, long-term environmental stability).

• 1 mark for explaining how adaptation contributes to sustainable development (e.g., infrastructure resilience, protection of communities, maintaining economic function).

• 1–2 marks for evaluation of how the two approaches complement each other or vary in effectiveness depending on regional vulnerability (e.g., mitigation tackles root causes but takes time; adaptation provides immediate protection; both needed for comprehensive sustainability).