AP Syllabus focus:

‘Congress’s enumerated and implied powers let it shape policy through fiscal decisions, including passing a federal budget, collecting taxes, borrowing money, and coining money.’

Congress’s fiscal powers are central to national policymaking because controlling money shapes what government can do. Through taxing, spending, and borrowing, Congress sets priorities, influences the economy, and checks the executive branch.

Constitutional basis of Congress’s fiscal authority

Congress’s influence over fiscal policy comes primarily from Article I, Section 8, which lists key legislative powers, and from the flexibility built into the Constitution for carrying those powers out.

Enumerated powers: Specific powers explicitly listed in the Constitution (especially in Article I) that Congress may exercise.

These include the authority to “lay and collect Taxes”, borrow money, and coin money, which together determine the federal government’s capacity to act.

Implied powers: Powers not explicitly listed but reasonably derived from enumerated powers, especially through the necessary and proper clause.

Implied powers matter because modern fiscal governance requires administrative systems (collection, enforcement, budgeting processes) beyond the Constitution’s brief text.

Passing a federal budget: how spending choices become policy

Fiscal decisions are policy decisions because they determine which programmes are funded, expanded, reduced, or eliminated. While the Constitution does not outline a detailed budget process, Congress uses its legislative authority to create and revise budget rules over time.

Core idea: spending requires congressional approval

Congress authorises programmes through statutes, but appropriations determine whether agencies actually receive money to operate.

Budgeting is a recurring way Congress can redirect priorities without rewriting every underlying law.

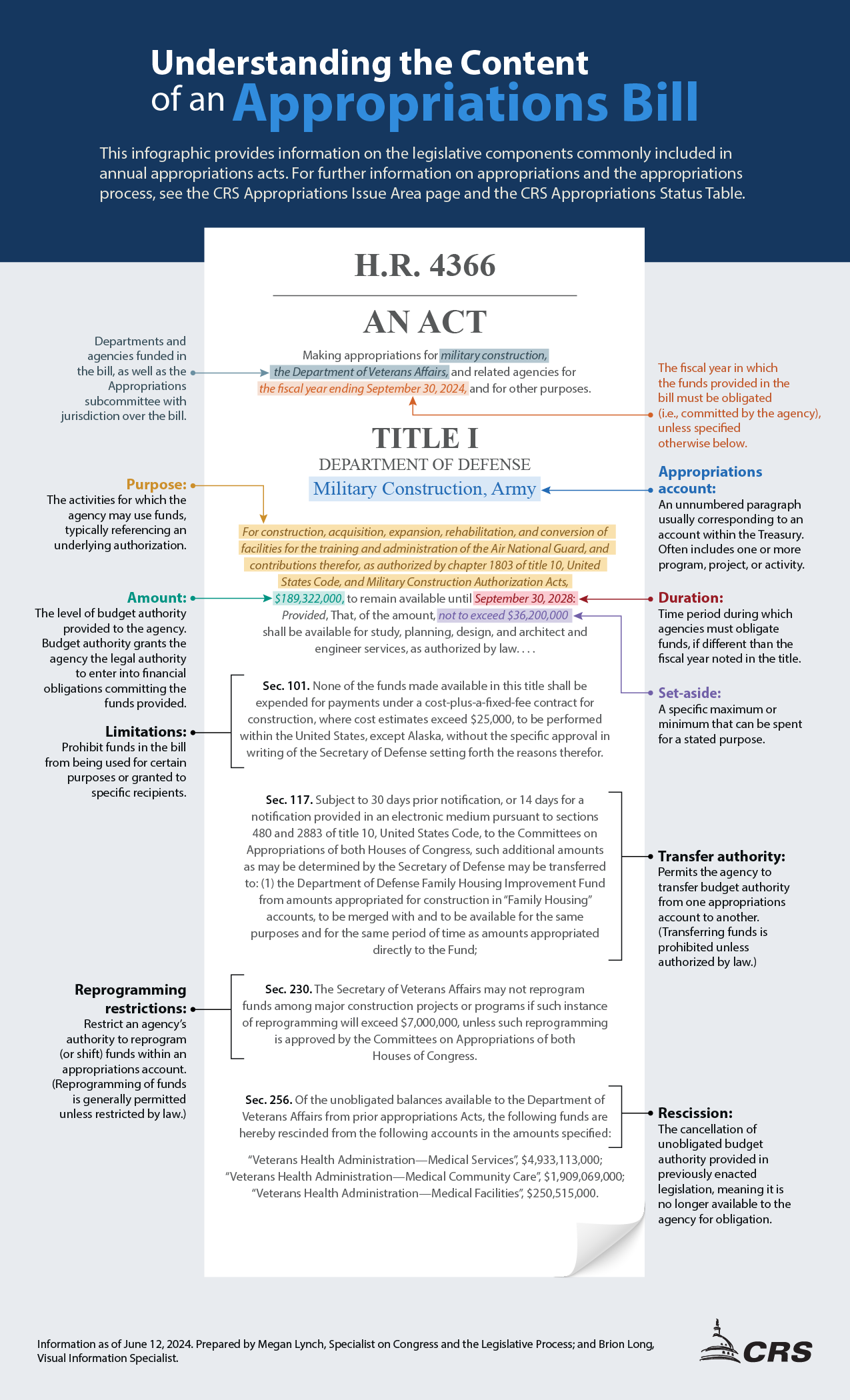

Appropriation: A law passed by Congress that provides legal authority for federal agencies to spend a specified amount for a specified purpose.

Because appropriations are time-limited or conditional, they give Congress leverage over how executive agencies implement policy.

CRS diagram showing the standard building blocks of an annual appropriations act—what is funded, how much budget authority is provided, how long funds remain available, and the legal limits Congress can attach (e.g., transfers, reprogramming restrictions, rescissions). It illustrates how Congress can shape real-world agency behavior through the specific legal text of appropriations, not just broad policy goals. Source

Collecting taxes: revenue power and policy design

Congress’s power to collect taxes allows it to raise revenue and also to influence behaviour and distribution through the structure of tax law.

What Congress controls through taxation

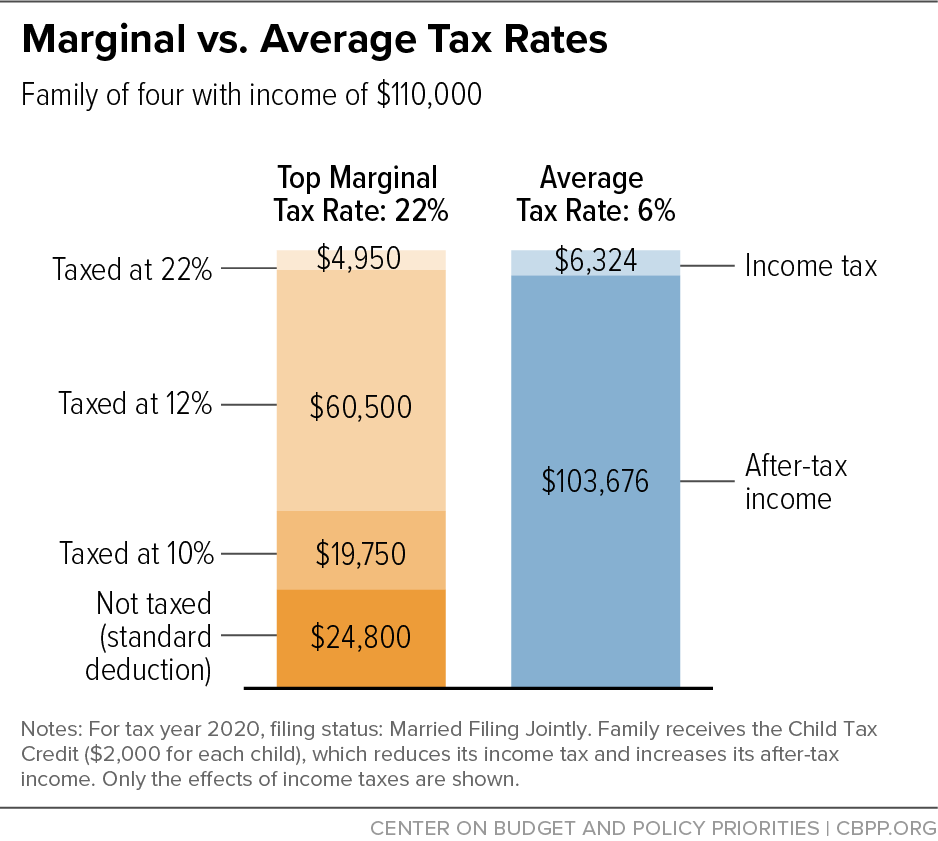

Tax bases: what is taxed (income, payroll, corporate profits, certain transactions)

Rates and brackets: how heavily different amounts or categories are taxed

Credits and deductions: targeted incentives that can encourage or discourage activities

Enforcement capacity: funding and statutory authority for tax administration

Tax policy is therefore both a funding mechanism and a tool for shaping economic outcomes, with political conflict often centred on who bears the burden and what goals tax provisions serve.

Bar-chart explanation of marginal versus average (effective) tax rates for a sample household, showing how income is taxed in layers across brackets while credits and deductions reduce the overall share paid. The visual makes clear why being “in a bracket” does not mean all income is taxed at that rate—only the last dollars are. Source

Borrowing money: deficits, debt, and legislative leverage

Congress’s power to borrow money on the credit of the United States enables the federal government to cover shortfalls when spending exceeds revenue.

Key implications of borrowing authority

Borrowing can finance urgent needs without immediate tax increases, but it increases public debt over time.

Fiscal conflict often arises over whether to prioritise cutting spending, raising taxes, or borrowing to maintain current commitments.

Because borrowing authority is statutory, it can become a bargaining tool in broader legislative negotiations over fiscal priorities.

Borrowing links directly to Congress’s checking role: the executive cannot sustain major initiatives long-term without Congress maintaining the legal framework for federal financing.

Coining money: monetary foundations and congressional power

Congress’s authority to coin money and regulate its value establishes the federal government’s role in defining legal tender and the monetary system’s foundations.

Why coinage power matters for policy

It supports national economic integration by standardising currency and reducing reliance on fragmented state or private alternatives.

It underpins federal credibility in taxation and borrowing by ensuring a stable unit of account for government finance.

While day-to-day monetary policy is typically carried out through institutions created by statute, Congress’s coinage power is the constitutional anchor for those arrangements and for the broader fiscal system.

FAQ

CBO provides non-partisan cost estimates (“scores”) and baseline projections that shape negotiations.

Its analyses influence which proposals are seen as affordable under existing budget rules, even though CBO cannot force Congress to adopt any recommendation.

Authorisation creates or continues a programme and may recommend funding levels.

Appropriation provides the legal permission to spend specific sums; without it, programmes may exist on paper but lack operational funding.

The debt ceiling is a statutory cap on total federal borrowing.

It does not itself create new spending but can constrain Treasury’s ability to finance obligations already enacted, making it a distinct pressure point in fiscal bargaining.

Seigniorage is the difference between the face value of money and the cost to produce it.

It matters because it represents a small source of government revenue and highlights how currency design intersects with fiscal capacity.

Tax expenditures are revenue losses from credits, deductions, and exclusions that function like spending through the tax code.

They can be politically durable because they look like tax cuts rather than direct outlays, yet they still shape policy priorities and the budget outlook.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Describe two fiscal powers of Congress listed in the Constitution.

1 mark for correctly describing the power to levy/collect taxes.

1 mark for correctly describing one of: passing spending/appropriations (budgeting), borrowing money, or coining money.

(6 marks) Explain how Congress’s enumerated and implied powers enable it to shape national policy through fiscal decisions.

1 mark for identifying that enumerated powers include taxation, borrowing, and coinage (any one, accurately stated).

1 mark for explaining that budgeting/appropriations determine which policies are funded and therefore implemented.

1 mark for explaining that tax design (rates, bases, credits/deductions) can shape behaviour or distribution as well as raise revenue.

1 mark for explaining that borrowing authority allows government to fund spending when revenues are insufficient, affecting policy sustainability.

1 mark for defining or accurately applying implied powers via the necessary and proper clause to create fiscal mechanisms/administration.

1 mark for linking fiscal control to inter-branch power (e.g., Congress constrains executive action by controlling revenue/spending authority).