AP Syllabus focus:

‘Congress must produce a budget with mandatory spending for entitlement programs and discretionary spending approved annually. Rising entitlement costs can squeeze discretionary spending unless revenues rise or deficits grow.’

The federal budget is Congress’s central tool for turning policy goals into action. Understanding the difference between mandatory and discretionary spending explains why some programmes grow automatically while others face yearly political fights.

Core idea: one budget, two major spending types

Congress authorises and funds federal activity through the annual budget process, but not all spending is decided the same way. The key distinction is whether spending occurs automatically under existing law or must be renewed through yearly appropriations.

Mandatory spending (entitlements)

Mandatory spending flows from laws that set eligibility rules and benefit formulas, so funding adjusts automatically based on who qualifies and what benefits cost.

Mandatory spending — federal spending required by existing law, largely for entitlement programmes, that occurs automatically without annual appropriations decisions.

Mandatory programmes are politically “sticky” because cutting costs often means changing eligibility, benefits, or the underlying statute—choices that can impose visible costs on large constituencies.

Discretionary spending (appropriations)

Discretionary spending is set through the annual appropriations process, so Congress revisits totals and priorities each year and can more readily increase, freeze, or cut funding.

Discretionary spending — federal spending that must be approved through annual appropriations acts and is therefore decided each fiscal year.

Because discretionary accounts require repeated votes, they are more exposed to partisanship, bargaining, and short-term political pressures.

How mandatory and discretionary spending shape Congress’s choices

Why the split matters for policymaking

Mandatory spending limits how much of the budget is “available” for new priorities because large portions are committed by law.

Discretionary spending is where Congress most visibly sets annual priorities, since amounts are revisited and debated each year.

The mix influences agenda-setting: lawmakers often fight hardest over the smaller share of spending that is truly negotiable annually.

Entitlements and the “squeeze” described in the syllabus

The syllabus emphasises that rising entitlement costs can squeeze discretionary spending unless revenues rise or deficits grow. This describes a structural budget pressure:

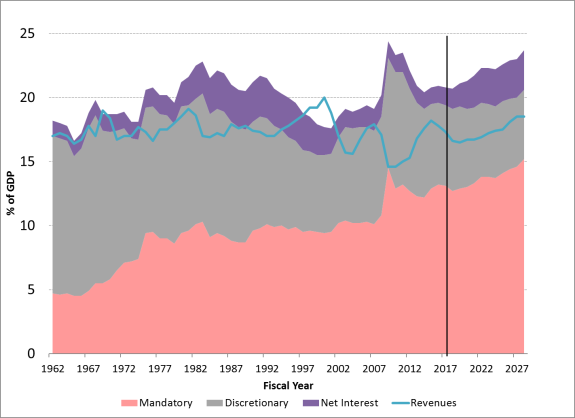

This stacked chart breaks total federal outlays into mandatory, discretionary, and net interest components, with a separate line showing revenues (all as a share of GDP). As the mandatory portion grows, the discretionary portion becomes a smaller and more contested slice of the budget unless revenues rise or borrowing expands. The visualization clarifies why entitlement-driven growth can create a long-run “squeeze” on annually appropriated programs. Source

If mandatory spending increases (for example, due to demographics or health-care costs), then—holding revenues constant—Congress faces fewer dollars for discretionary programmes.

Congress can respond by:

increasing revenues (raising taxes or broadening the tax base), or

accepting larger deficits, which increases borrowing, or

reducing discretionary spending (or changing mandatory laws, which is often politically difficult).

Revenues, deficits, and the basic budget identity

Budget debates often turn on whether Congress will match spending to revenues or borrow to cover the gap.

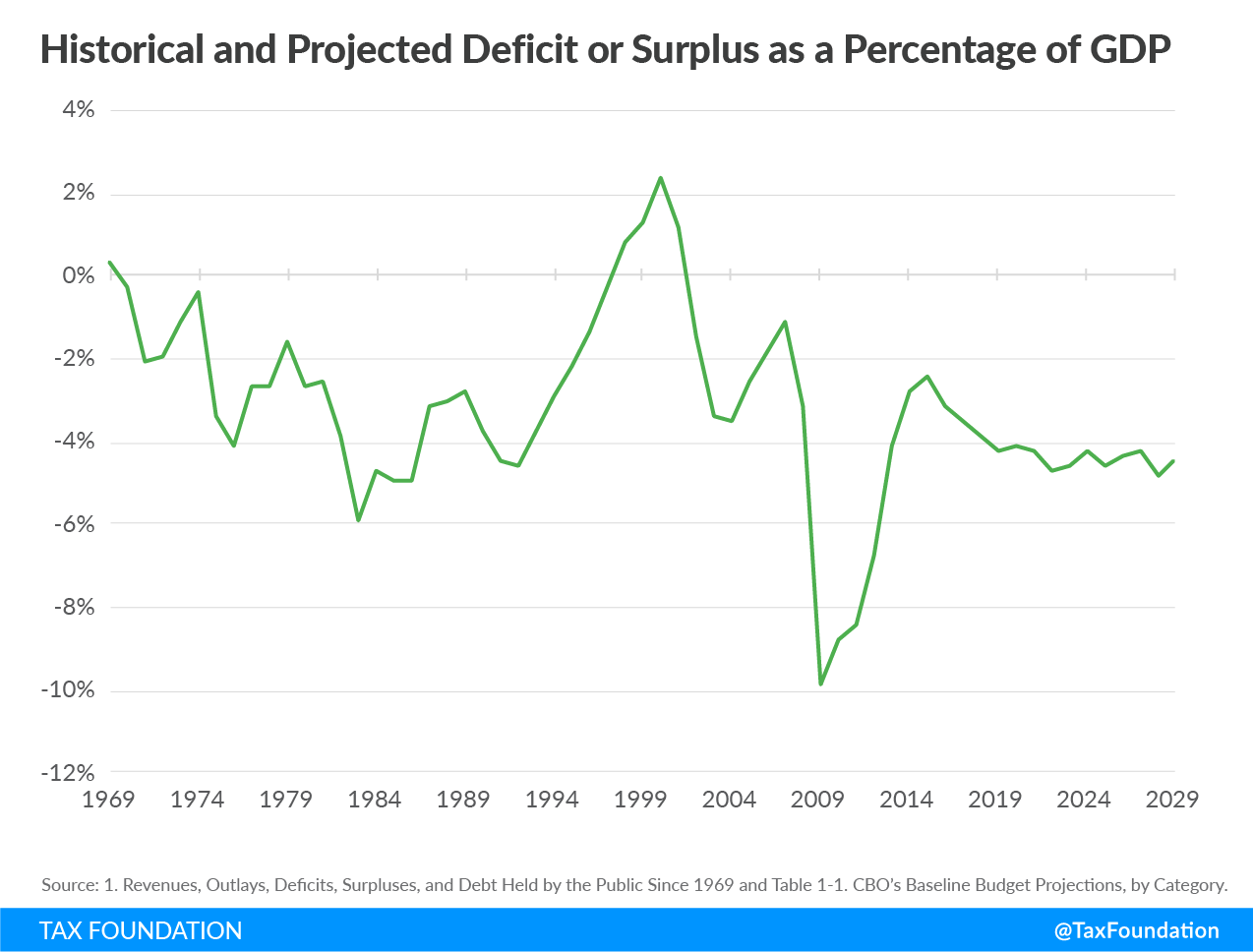

This chart summarizes long-run federal revenues, outlays, and the resulting deficit/surplus as shares of GDP using CBO-based data. It shows how fiscal balance changes over time and helps students connect political debates (taxing, spending, borrowing) to a persistent empirical pattern. Reading it alongside the identity makes the deficit concept visually concrete. Source

EQUATION

= Annual deficit, in dollars

= Total federal spending in a fiscal year, in dollars

= Total federal revenue collected in a fiscal year, in dollars

When outlays exceed revenues, Congress authorises borrowing to finance the difference; persistent deficits can change the politics of both mandatory reforms and annual discretionary allocations.

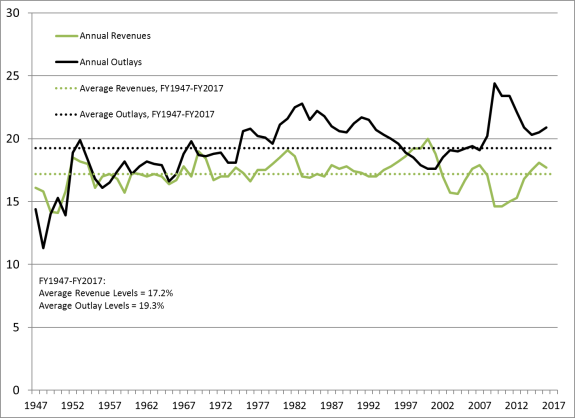

This figure plots federal outlays and revenues as a percentage of GDP over time, making it easy to see when the two lines diverge. The vertical gap between outlays and revenues corresponds to the annual deficit (or surplus when revenues exceed outlays). By expressing values as a share of GDP, the graph highlights how budget imbalance can persist even as the economy grows. Source

Practical implications for AP-level analysis

What Congress “must” do versus what it “chooses” to do

Congress must produce a budget that accounts for mandatory commitments and sets annual discretionary levels.

Congress has more routine control over discretionary spending approved annually, because it is revisited in appropriations bills.

Congress’s control over mandatory spending is more indirect: it requires changing the underlying entitlement laws rather than simply adjusting an annual funding line.

How the distinction affects conflict and compromise

Budget conflict often intensifies when lawmakers disagree about:

whether to protect or expand entitlement programmes,

whether to prioritise particular discretionary areas,

whether to raise revenues or tolerate higher deficits.

The “squeeze” dynamic helps explain why some discretionary areas face recurring pressure even when overall federal spending is rising.

FAQ

Entitlements are driven by statutory rules rather than annual appropriations.

Increases can come from more eligible recipients, higher per-person costs, or automatic adjustments written into law.

A continuing resolution temporarily extends prior funding levels when new appropriations are not enacted.

It matters mainly for discretionary programmes because they depend on annual appropriations to keep agencies operating at funded levels.

Some mandatory programmes use trust-fund accounting tied to dedicated revenue streams.

However, trust-fund balances and projected inflows can constrain policy options, prompting debates about benefit formulas, eligibility, or revenue sources.

Baseline projections estimate future spending under current law.

They often show mandatory spending rising automatically, which can shape perceptions of what counts as a “cut” versus slower growth.

Discretionary cuts can be made through annual appropriations with fewer statutory changes.

Mandatory reforms usually require rewriting benefit or eligibility rules, which can mobilise broad and organised opposition from affected beneficiaries.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain the difference between mandatory spending and discretionary spending in the US federal budget.

1 mark: Defines mandatory spending as required by existing law (often entitlements) and not needing annual approval.

1 mark: Defines discretionary spending as set through annual appropriations and requiring yearly approval.

(6 marks) Using the concept of mandatory versus discretionary spending, analyse how rising entitlement costs can affect Congress’s annual budgeting choices. In your answer, refer to revenues and/or deficits.

1 mark: Identifies that entitlement programmes are a major component of mandatory spending.

1 mark: Explains that mandatory spending rises automatically under existing law when costs/eligibility increase.

1 mark: Explains the “squeeze” on discretionary spending because less budget capacity remains for annually appropriated programmes.

1 mark: Explains one response: increase revenues (e.g., higher taxes) to accommodate higher mandatory costs.

1 mark: Explains an alternative response: allow larger deficits/borrowing when outlays exceed revenues (can be stated as ).

1 mark: Develops analysis by linking the trade-off to congressional choice/conflict (e.g., prioritisation, difficulty of changing entitlement laws versus cutting discretionary items).