AP Syllabus focus:

‘Policy conflict with Congress’s agenda can push presidents to use executive orders and directives to bureaucracy to advance their own agenda items despite legislative resistance.’

Presidents often face a Congress that will not pass their preferred bills. When legislative bargaining fails, presidents may try to move policy through the executive branch by directing agencies to act within existing legal authority.

Core Idea: Acting Without New Statutes

When Congress blocks, delays, or rewrites a president’s priorities, the president may still influence policy by using unilateral executive action—especially instructions to executive agencies (the bureaucracy). These actions do not create new laws; they attempt to shape how existing laws are administered.

Executive Orders vs. Directives

Presidents use multiple tools to guide bureaucratic behaviour, varying in visibility and formality.

Executive order: A written, formal instruction from the president to executive branch officials that directs how the executive branch will implement or enforce law, grounded in constitutional authority or authority delegated by Congress.

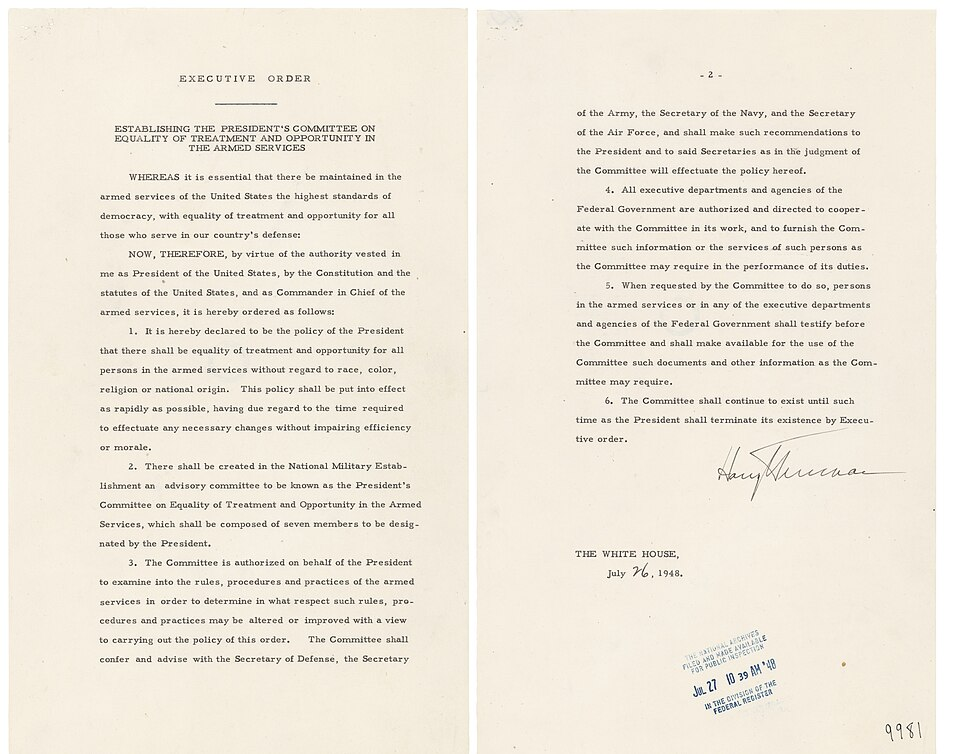

This image reproduces Executive Order 9981 (July 26, 1948), a primary-source example of a presidential order issued to direct executive-branch implementation. Seeing the document’s formal structure (title, authority language, and signature) helps clarify how executive orders function as written instructions to the bureaucracy rather than new statutes. Source

Executive action also includes less formal but still powerful written and verbal instructions.

Directive (to the bureaucracy): A presidential instruction—often issued as a memorandum, guidance, or internal order—telling agencies how to prioritise, interpret, or administer policy within their operational authority.

Why Conflict with Congress Produces Executive Action

Presidents are incentivised to use orders and directives when Congress resists because:

Gridlock and partisan opposition make passing new legislation difficult.

The president can act faster through the executive branch than through the legislative process.

Agencies already possess delegated discretion that can be steered toward presidential goals.

What Presidents Are Trying to Achieve

Orders and directives commonly aim to:

Reprioritise enforcement (e.g., focusing resources on certain violations over others).

Accelerate or slow implementation of existing statutory programmes.

Coordinate agency action across departments to pursue a single agenda item.

Signal commitment to a policy to shape public debate and pressure Congress.

How Directives Work Inside the Bureaucracy

Presidential control depends on the bureaucracy’s role as the implementer of federal policy. Directives typically operate by:

Setting policy priorities for agency leadership.

Instructing agencies to propose, revise, or rescind regulations consistent with the president’s agenda.

Reallocating attention and resources through managerial commands (within legal limits).

Limits and Risks (Why Congress Still Matters)

Even when presidents act unilaterally, constraints remain:

Statutory limits: Agencies must stay within authority Congress granted; actions that exceed that authority can be challenged.

Funding dependence: Congress controls appropriations; resource limits can blunt enforcement and implementation goals.

Administrative friction: Career officials may interpret directives narrowly, delay execution, or raise compliance concerns.

Political blowback: Congress may respond with hearings, restrictive language in bills, or public criticism.

This photograph depicts a congressional committee hearing setting, highlighting the hearing as a central tool of legislative oversight. It visually reinforces how Congress can respond to executive-branch actions by calling witnesses, gathering information publicly, and shaping the political narrative around administration and implementation. Source

Checks and Branch Competition

This subsubtopic centres on interbranch conflict: Congress uses legislation and oversight to set the agenda, while presidents may use executive orders and bureaucratic directives to pursue their own agenda despite legislative resistance. The result is often policy made through administration and management rather than new statutes.

FAQ

Presidents can rely on lower-visibility written instructions (memoranda) and management channels.

This can:

reduce immediate political scrutiny

speed coordination across agencies

still bind agency priorities, depending on internal enforcement

Speed often depends on operational factors.

Key accelerators include:

clear, measurable instructions

alignment with existing agency capacity

support from politically appointed leadership

minimal need for new regulatory procedures

Agencies translate broad goals into workable steps.

Common patterns:

narrowing the directive to fit existing statutory authority

issuing internal guidance to field offices

prioritising “easy wins” that avoid complex procedural hurdles

Legal advisers help reduce vulnerability to challenge.

They typically:

check the statutory basis for action

assess separation-of-powers risks

recommend narrower wording to stay within delegated authority

Enforcement shifts can be administratively simpler.

They may:

require fewer formal procedures

produce faster, visible results

be adjusted as conditions change, though still constrained by law and resources

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one reason a president might use an executive order or directive to the bureaucracy when Congress disagrees with the president’s agenda.

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason linked to congressional resistance (e.g., gridlock, opposition majority, legislative delay).

1 mark: Explains how unilateral action through agencies can advance policy without passing a new law (e.g., changing enforcement priorities or implementation).

(6 marks) Describe how executive orders and directives to the bureaucracy can be used to advance a president’s agenda despite legislative resistance, and analyse two limitations on this strategy.

2 marks (Description): Accurate description of executive orders/directives as instructions to executive agencies shaping implementation/enforcement within existing law.

2 marks (Limitation 1 + analysis): One limitation identified and analysed (e.g., statutory constraints and risk of acting beyond delegated authority).

2 marks (Limitation 2 + analysis): A different limitation identified and analysed (e.g., congressional funding control, oversight pressure, or bureaucratic resistance).