AP Syllabus focus:

‘Stare decisis means courts generally follow prior decisions in cases with similar facts. This doctrine promotes stability and shapes how judges decide new disputes.’

Stare decisis is a core judicial practice that links today’s constitutional disputes to yesterday’s rulings. Understanding how precedent works clarifies why many cases are decided incrementally and why some landmark decisions are difficult to overturn.

What stare decisis requires

Stare decisis guides judges to treat prior decisions as authoritative when later disputes present similar facts and the same legal question, promoting stability and predictability in the law.

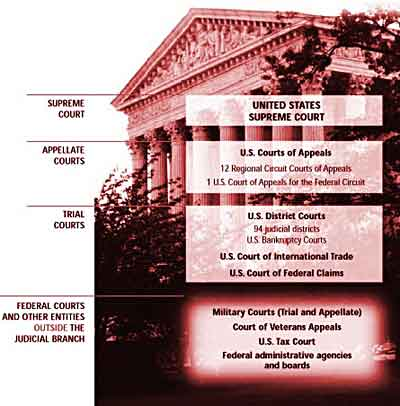

This diagram summarizes the structure of the federal judiciary, highlighting the vertical chain from trial courts to appellate courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. It reinforces the logic of vertical stare decisis: lower courts are expected to follow the constitutional holdings of higher courts in the same system. The tiered layout also helps explain why precedent can promote uniformity and predictability across many cases. Source

Stare decisis: The doctrine that courts generally follow prior judicial decisions (precedents) when deciding cases with similar facts and legal issues.

In practice, stare decisis does not mean “never change.” It means judges start from existing precedent and must justify departures from it.

Precedent and what counts as binding

A past case becomes precedent for later courts, but not every sentence in an opinion has the same force. Courts focus on the part of a decision necessary to resolve the dispute.

Precedent: A prior court decision used as an authority for deciding later cases with similar facts or legal questions.

Key distinctions that shape how strongly precedent applies:

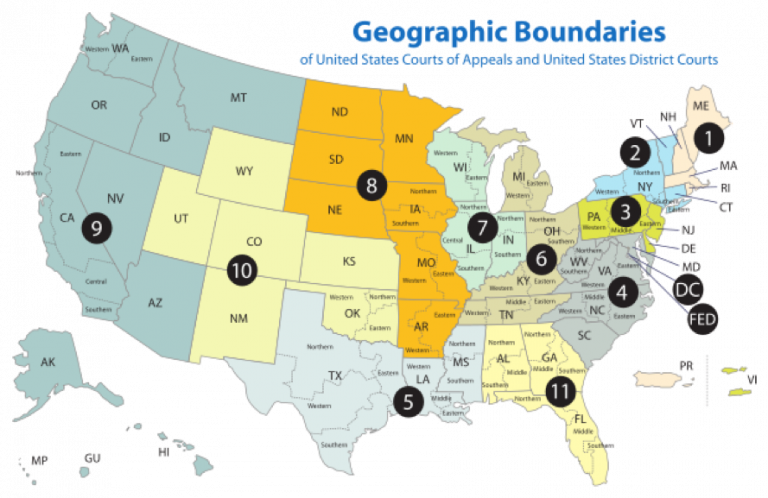

This map shows the geographic boundaries of the federal judicial circuits (U.S. Courts of Appeals). It helps explain why a published circuit court holding is binding on federal district courts within that circuit, but typically only persuasive in other circuits. Seeing the circuit layout makes “binding vs. persuasive precedent” concrete by tying authority to judicial hierarchy and geography. Source

Binding precedent: Must be followed by lower courts in the same judicial hierarchy (e.g., federal district courts follow Supreme Court constitutional holdings).

Persuasive precedent: May influence a court but is not mandatory (e.g., another jurisdiction’s reasoning).

Holding: The legal rule essential to deciding the case; the primary source of precedent.

Dicta (obiter dicta): Comments not necessary to the outcome; often cited but generally not binding.

How precedent shapes judicial decision-making

Stare decisis “shapes how judges decide new disputes” by narrowing the range of legitimate outcomes. Judges often frame decisions as consistent with earlier rulings to strengthen legal legitimacy and reduce disruption.

Common ways courts use precedent:

Analogising: Showing the current facts are materially similar to a prior case, so the same rule should apply.

Distinguishing: Explaining why factual or legal differences make a prior case inapplicable, allowing a different outcome without overruling.

Extending: Applying an established rule to a new but closely related situation, expanding precedent’s reach.

Because many disputes arise from new technology or new political conflicts, courts frequently debate whether differences are “material” enough to distinguish a case.

Why the doctrine promotes stability

The syllabus emphasises that stare decisis “promotes stability.” It does this by:

Encouraging uniformity across cases, so similar parties are treated similarly.

Increasing predictability, helping individuals, interest groups, and governments anticipate how rules will be applied.

Supporting the Court’s institutional legitimacy, since decisions appear grounded in law rather than shifting preferences.

Constraining judges, making outcomes less dependent on any single judge’s policy views.

Stability is especially important in constitutional law, where reversal is hard to fix through ordinary legislation.

When and why courts depart from precedent

Courts sometimes decide that adherence to precedent would entrench error or produce unworkable rules. Departures typically occur through:

Overruling: Explicitly rejecting an earlier holding and replacing it with a new rule.

Narrowing: Keeping the precedent formally intact but limiting it to specific circumstances.

Reinterpreting: Reading earlier holdings in a constrained way to reduce their effect.

Factors judges often weigh when considering overruling include:

Quality of reasoning in the prior decision

Workability of the rule in practice

Reliance interests (whether people and institutions structured behaviour around the old rule)

Consistency with related precedents and constitutional principles

Changed facts or understanding that undermine the old rationale

Limits and controversies

Stare decisis can create tension between stability and constitutional interpretation:

Strong adherence can preserve rules many view as wrongly decided.

Frequent overruling can make constitutional rights feel contingent on Court membership.

Disagreement over what counts as the “same” facts or issue can make precedent seem flexible.

These tensions ensure that precedent remains central to how judges justify decisions—even when they ultimately choose to follow, distinguish, or overturn earlier cases.

FAQ

They assess whether the earlier holding depended on the specific fact at issue.

Courts often ask: if that fact changed, would the legal rule or outcome logically change?

Reliance interests are the ways people, businesses, and governments structure decisions around an existing rule.

The stronger the reliance, the more disruptive overruling may be.

Its constitutional holdings bind lower federal courts and state courts on federal constitutional questions.

Other parts of an opinion may be persuasive rather than binding.

Yes. Courts can narrow a rule to unusual facts, interpret it strictly, or treat later cases as materially different.

This can reduce a precedent’s practical reach over time.

Dicta can signal how judges think about future disputes.

Later courts may adopt dicta’s reasoning, turning it into a holding when the issue becomes necessary to decide.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define stare decisis and explain one way it affects how judges decide a new dispute.

1 mark: Accurate definition of stare decisis (generally following prior decisions in similar cases).

1 mark: Explains one effect (e.g., promotes predictability/stability; constrains outcomes; encourages reliance on holdings).

(5 marks) Explain how precedent can both constrain and enable judicial change. In your answer, distinguish between at least two methods courts use to handle prior decisions.

1 mark: Explains constraint (e.g., binding precedent/legitimacy/predictability narrows outcomes).

1 mark: Explains how change is enabled despite precedent (law adapts through interpretation).

1 mark: Correctly distinguishes two methods (e.g., distinguishing vs overruling; narrowing vs extending).

1 mark: Accurate explanation of first method’s operation.

1 mark: Accurate explanation of second method’s operation.