AP Syllabus focus:

‘Supreme Court decisions declared that race‑based school segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.’

Race-based school segregation became a central constitutional conflict because education shapes citizenship and opportunity. Supreme Court rulings transformed the meaning of equality, expanded federal judicial authority, and forced states to dismantle segregated public school systems.

Constitutional foundation: equality and state action

Equal protection and segregation

The Court’s anti-segregation rulings rest on the idea that state-sponsored separation by race is inconsistent with constitutional equality, even when facilities appear comparable.

Equal Protection Clause: The Fourteenth Amendment requirement that states provide equal protection of the laws, restricting states from treating people differently without sufficient constitutional justification.

What the Court was addressing

De jure segregation (segregation by law) in public schools, enforced through state constitutions, statutes, and local policies

The constitutional question: whether state-mandated separate schooling can ever satisfy equal protection

Key rulings that ended race-based school segregation

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): “Separate” is inherently unequal

Brown v. Board of Education overturned the logic that separation could be constitutional if resources were equal.

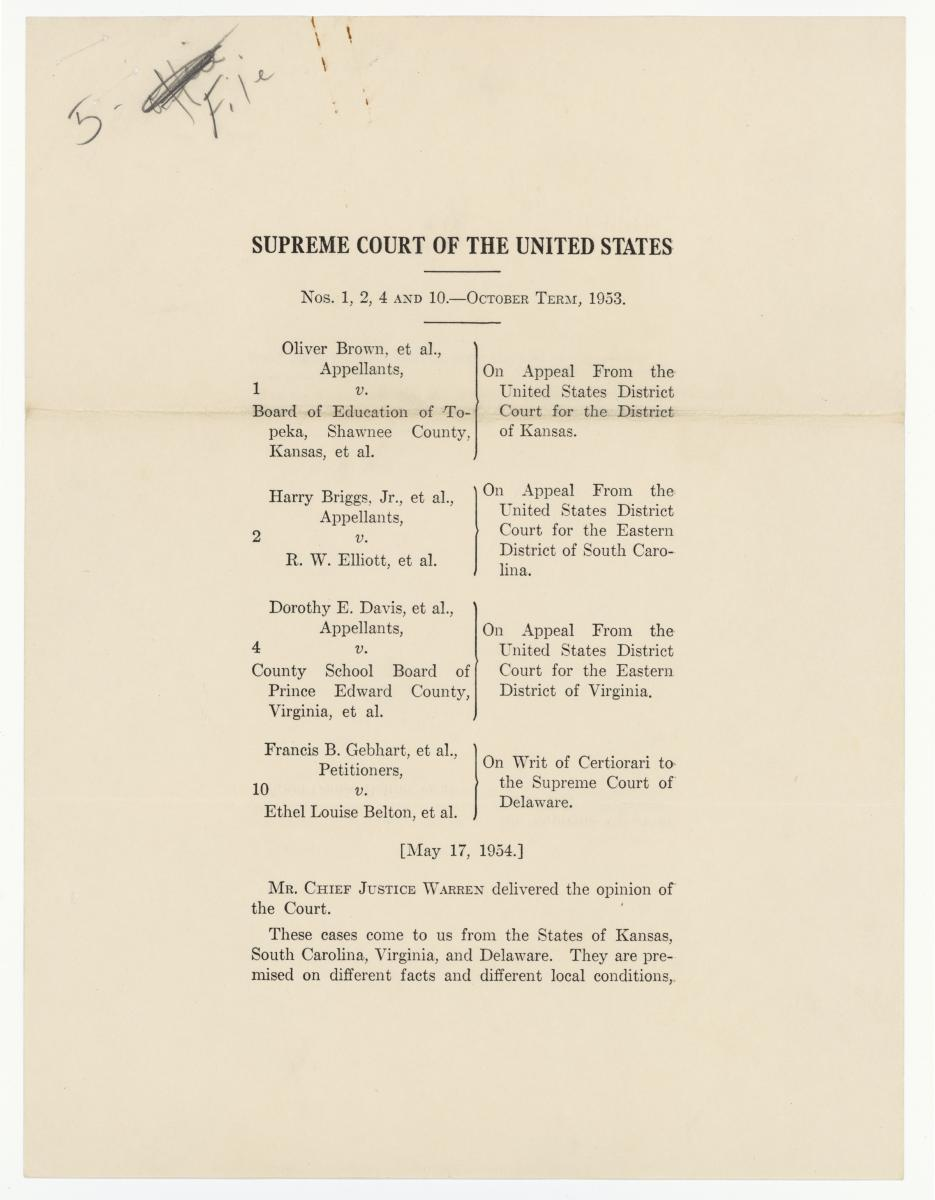

First page of the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), as preserved by the National Archives. Using this document helps students connect the course theme (Equal Protection) to the Court’s authoritative written ruling rather than a secondary summary. Source

The Court held that segregated public education violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause

Core reasoning focused on education’s central role and the harms imposed by state-enforced racial separation

Practical impact: Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” framework became unconstitutional in public schooling

Brown II (1955): implementation and “all deliberate speed”

A year later, the Court confronted how to enforce desegregation.

Ordered districts to desegregate with “all deliberate speed”

Assigned federal district courts oversight of local compliance

Result: gradualism, delays, and extensive litigation as states and districts resisted or minimized change

Bolling v. Sharpe (1954): applying anti-segregation principles to the federal government

Segregation in Washington, D.C. implicated federal rather than state authority.

The Court used Fifth Amendment due process reasoning to reach a parallel anti-segregation result for federally controlled schools

Significance: reinforced a national constitutional commitment against government-sponsored school segregation

Enforcing desegregation: federal supremacy and remedial power

Cooper v. Aaron (1958): states must obey Supreme Court interpretations

When state officials attempted to block desegregation, the Court strengthened judicial authority.

Held that states are bound by the Supreme Court’s constitutional rulings

Reinforced federal supremacy in constitutional interpretation, limiting interposition/nullification strategies

Green v. New Kent County (1968): ending “freedom of choice” evasions

Districts sometimes adopted nominally neutral plans that preserved segregation.

The Court required meaningful movement toward dismantling segregated systems

Emphasised an affirmative duty to eliminate segregation “root and branch,” not merely remove explicit racial assignment rules

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971): remedies including busing

The Court addressed what tools judges could use to convert segregated systems into integrated ones.

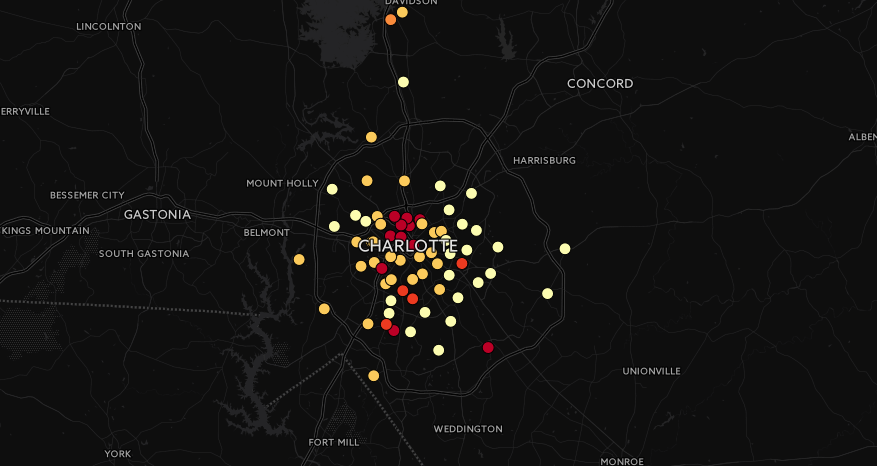

Map visualization of Charlotte’s school racial composition around 1970, showing a concentrated core of predominantly Black schools surrounded by whiter suburban schools. This spatial pattern helps explain why Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971) upheld robust remedial tools—like re-zoning and busing—to convert legally segregated systems into integrated ones. Source

Approved broad remedial authority for federal courts where de jure segregation had been proven

Permitted race-conscious measures (including busing and redrawn attendance zones) as tools to cure constitutional violations

Limited by purpose: remedies must be tied to correcting state-created segregation

What these rulings changed (and why it matters for AP Gov)

Legal rule students should be able to state

Supreme Court decisions declared that race‑based school segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Ongoing constitutional themes tested in desegregation cases

Judicial review and legitimacy: the Court interpreting equality beyond formal resource comparisons

Federalism: tension between state control of education and federal constitutional limits

Compliance and capacity: courts relying on district judges, monitoring, and tailored remedies to turn constitutional principle into practice

Line between principle and remedy: declaring segregation unconstitutional (Brown) versus designing enforceable solutions (Green, Swann)

FAQ

Because education was framed as foundational to civic participation and life chances, making unequal access especially damaging.

The Court relied on the real-world role of schooling, not just formal legal categories.

They combined legal arguments about state classification by race with factual records about harms.

Evidence often included:

inequality in opportunities and curricula

impacts on students’ status and treatment within the community

They used ongoing jurisdiction: approving plans, setting deadlines, requiring reports, and responding to motions alleging noncompliance.

This could involve multiple rounds of plan revisions over years.

The key distinction was whether a remedy was narrowly connected to curing proven government-caused segregation.

Remedies were more defensible when tailored to identified constitutional violations within a district.

Resistance, administrative complexity, and demographic shifts made implementation difficult.

Additionally, litigation often turned from the constitutional rule to the scope, duration, and limits of judicially supervised remedies.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify the constitutional provision the Supreme Court relied on to hold that race-based school segregation in state public schools is unconstitutional.

1 mark: Identifies the Fourteenth Amendment.

1 mark: Specifies the Equal Protection Clause (or “equal protection of the laws”).

(6 marks) Explain how Supreme Court rulings both (a) declared school segregation unconstitutional and (b) strengthened the federal judiciary’s ability to enforce desegregation against resistant states and districts.

2 marks: Explains Brown v. Board of Education: segregation in public education violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause; “separate” schooling is inherently unequal.

2 marks: Explains an enforcement-focused ruling (e.g., Green requiring effective desegregation beyond token plans, or Swann approving robust remedies like busing/rezoning tied to de jure segregation).

2 marks: Explains federal judicial supremacy/compliance (e.g., Cooper v. Aaron: states are bound by Supreme Court constitutional interpretations; federal courts can supervise implementation).