AP Syllabus focus:

‘The impact of polling depends on the reliability and veracity (truthfulness) of public opinion data used to support claims.’

Public opinion claims can sway voters, influence media narratives, and pressure officials. Because polls are estimates, responsible interpretation requires judging whether the data are dependable and whether the conclusions drawn from them are truthful.

Reliability and veracity: what you are evaluating

Reliability focuses on whether a poll’s results are consistent and dependable given how it was conducted. Veracity focuses on whether a polling-based claim is truthful, accurately represented, and supported by the data (not exaggerated or misleading).

Veracity: The truthfulness of a polling claim—whether the data are authentic, presented honestly, and interpreted in a way the evidence justifies.

A poll may be reliable yet still be used to make a low-veracity claim (for example, overstating what the results mean).

Assessing reliability (dependability of the poll)

Reliable polls reduce random error and avoid systematic bias. Key indicators of reliability include transparent methods, a credible sample, and stable procedures.

Major threats to reliability

Sampling problems: a sample that is too small, unrepresentative, or poorly recruited can produce unstable estimates.

Nonresponse bias: if certain groups are less likely to respond, results may skew even if the sample size is large.

Question effects: leading phrasing, confusing wording, or different question order can change answers and reduce consistency.

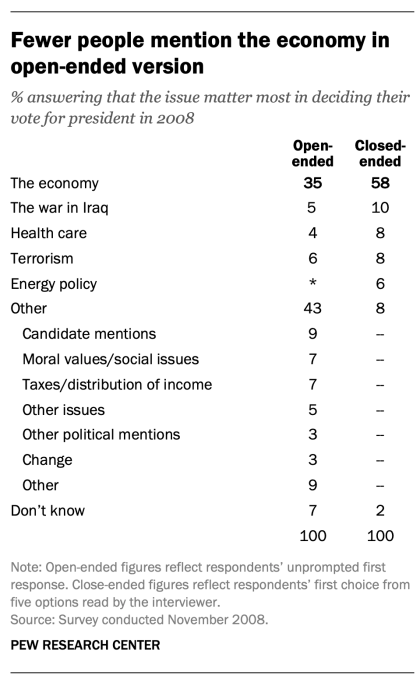

A Pew Research Center chart comparing responses to an open-ended versus a closed-ended survey question about the “most important issue” in the 2008 presidential vote. The figure demonstrates that offering response options (e.g., explicitly listing “the economy”) can substantially shift measured public opinion, underscoring why question format is a major source of measurement error in polling. Source

Timing effects: polls taken immediately after a major event can capture short-term reactions rather than stable attitudes.

Mode effects: phone, online, and text-to-web approaches can yield different response patterns if not carefully adjusted.

Likely voter screens: estimating who will vote can add uncertainty; different models can change toplines.

EQUATION

\text{MOE} n=1000 p \text{MOE} $ = Margin of error at a stated confidence level, in percentage points

Reliability improves when the pollster clearly reports the population, dates, sample size, mode, and method of weighting.

Assessing veracity (truthfulness of the claim made from the poll)

Veracity is about the honesty and logic of the argument built on polling. High-veracity claims match what the poll actually measured and acknowledge uncertainty.

Common ways polling claims become misleading

Cherry-picking: highlighting one favourable poll while ignoring other credible polls showing different results.

Overprecision: treating a small lead within the MOE as definitive proof of who is “ahead.”

False generalisation: using a poll of a narrow group (for example, registered voters in one state) to claim “Americans think…”

Causation claims: asserting a policy “caused” opinion change when the poll only shows correlation or a single time point.

Unreported uncertainty: omitting field dates, sample details, or MOE so readers cannot judge how strong the evidence is.

Sponsor influence and selective release: interest groups may publicise only results that help their position.

A practical checklist for judging polling claims

When you see a headline or a political argument citing a poll, focus on whether the poll is reliable and whether the claim is truthful:

Who conducted and funded it? Look for reputable organisations and full disclosures.

Who was surveyed? Adults vs registered voters vs likely voters; national vs district/state.

When was it fielded? Check whether results might reflect a temporary event-driven spike.

What exactly was asked? The claim should match the question’s wording and scope.

How is the result framed? Watch for language that exceeds the evidence (for example, “mandate,” “landslide,” “most people”).

Are comparisons valid? Trends require consistent question wording and similar methods across time.

Is the full report available? High-veracity use typically links to crosstabs, methodology, and complete question text.

FAQ

Aggregators combine multiple polls to reduce reliance on any one method or house effect.

They can still mislead if they exclude polls selectively or ignore differences in quality and timing.

House effects are consistent skews associated with a particular pollster’s methods.

They matter because two reliable-looking polls may differ systematically, complicating trend claims.

Stronger language is warranted when key methodology is missing, the sample is clearly inappropriate, or the question is manipulative.

Uncertainty alone (e.g., a close result) is not the same as untrustworthiness.

Full question wording and order

Population surveyed and dates

Sample size, mode, and weighting

Clear statement of uncertainty (e.g., MOE)

These allow readers to verify the claim.

Internal polls are commissioned by campaigns and may be selectively released.

A veracious use requires extra transparency, because outsiders cannot easily check withheld findings or full questionnaires.

Practice Questions

Define “veracity” in the context of polling claims and state one reason a veracious claim might still be uncertain. (2 marks)

1 mark: Accurate definition of veracity (truthfulness/accurate representation of polling data).

1 mark: Identifies uncertainty (e.g., sampling error/MOE, timing effects, nonresponse, model uncertainty).

A commentator states: “This new poll proves voters have turned against the policy nationwide, and the election outcome is now clear.” Explain two reliability checks you would apply to the poll and evaluate two ways the commentator’s claim could lack veracity. (6 marks)

2 marks (1+1): Two distinct reliability checks (e.g., sample/population, field dates, method/mode, transparency, weighting, likely voter screen).

4 marks (2+2): Two valid evaluations of low veracity (e.g., overclaiming “proves,” ignoring MOE, false generalisation to “nationwide,” certainty about election outcome, causation claim, cherry-picking).