AP Syllabus focus:

‘Campaign finance laws and court cases reflect an ongoing debate about money in politics and free speech under the First Amendment.’

Modern U.S. elections depend heavily on fundraising and political spending. Campaign finance rules attempt to prevent corruption and preserve political equality, while critics argue that limiting spending restricts constitutionally protected political expression.

Core tension: regulation vs. free speech

Why money matters in elections

Political campaigns require funds to communicate with voters and compete effectively (advertising, staff, data, travel, voter outreach). Because spending can amplify political messages, rules about money shape who can participate and whose voices are heard.

Higher costs can advantage candidates with:

Wealthy donors or self-funding capacity

Strong party networks and established name recognition

Connections to organised donor communities

The constitutional argument

Debates are rooted in the First Amendment, especially protections for political speech and association.

First Amendment: The constitutional protection of freedoms of speech, press, assembly, petition, and religion; central to arguments that political spending and fundraising involve protected political expression and association.

Supporters of broad First Amendment protection argue that spending is a tool for distributing ideas (e.g., buying airtime, printing materials) and that the government should not decide which voices may speak most effectively.

The anti-corruption rationale for campaign finance laws

What government tries to prevent

Pro-regulation arguments stress that unregulated money can undermine democratic responsiveness by encouraging corruption or the appearance of corruption.

Key concerns include:

Quid pro quo exchanges (money traded for official action)

Preferential access to officeholders for major donors

Policy responsiveness skewed toward large contributors rather than average constituents

A major goal of campaign finance law is to protect public trust so that elected officials appear accountable to voters rather than financial backers.

Limits as a balancing tool

In practice, the debate often turns on what kinds of limits are justified:

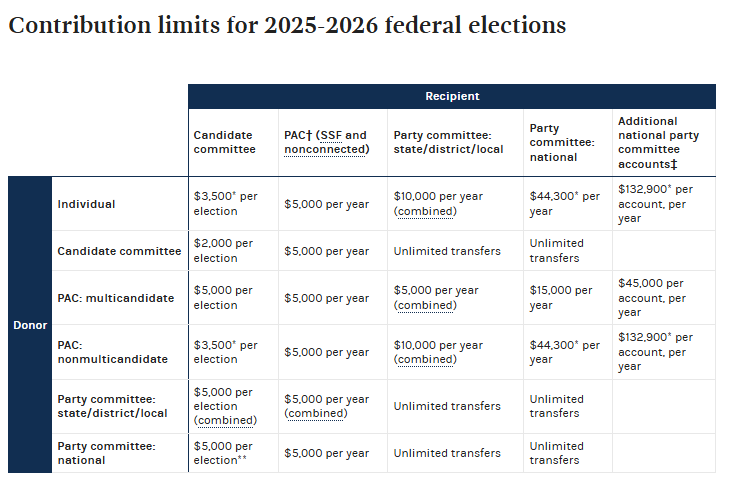

This Federal Election Commission chart summarizes federal contribution limits (e.g., how much an individual may give to a candidate committee per election versus to party committees per year). It helps clarify what campaign finance law most directly regulates: giving money to candidates and political committees, not simply political advocacy in general. Use it to connect the anti-corruption rationale to concrete dollar limits and regulated pathways for money entering campaigns. Source

Contribution limits are commonly defended as reducing corrupting influence on candidates and officeholders.

Spending limits are more controversial because they can directly restrict political communication.

The political equality argument (and its critics)

Equality and democratic fairness

Another major justification for regulation is political equality: the idea that elections should not be dominated by a small group of wealthy individuals or organisations.

Regulation advocates argue that concentrated wealth can:

Drown out less-funded candidates and groups

Reduce competition and weaken accountability

Shift agendas toward donor priorities

Critiques of equality-based regulation

Opponents respond that:

The First Amendment protects unpopular or minority viewpoints that may require funding to be heard.

Restricting spending can entrench incumbents and well-known candidates by limiting challengers’ ability to gain visibility.

Government attempts to “equalise” influence risk becoming partisan tools that shape electoral competition.

How court cases shape the debate

Campaign finance disputes frequently end up in court because election rules regulate core political activity.

Courts weigh:

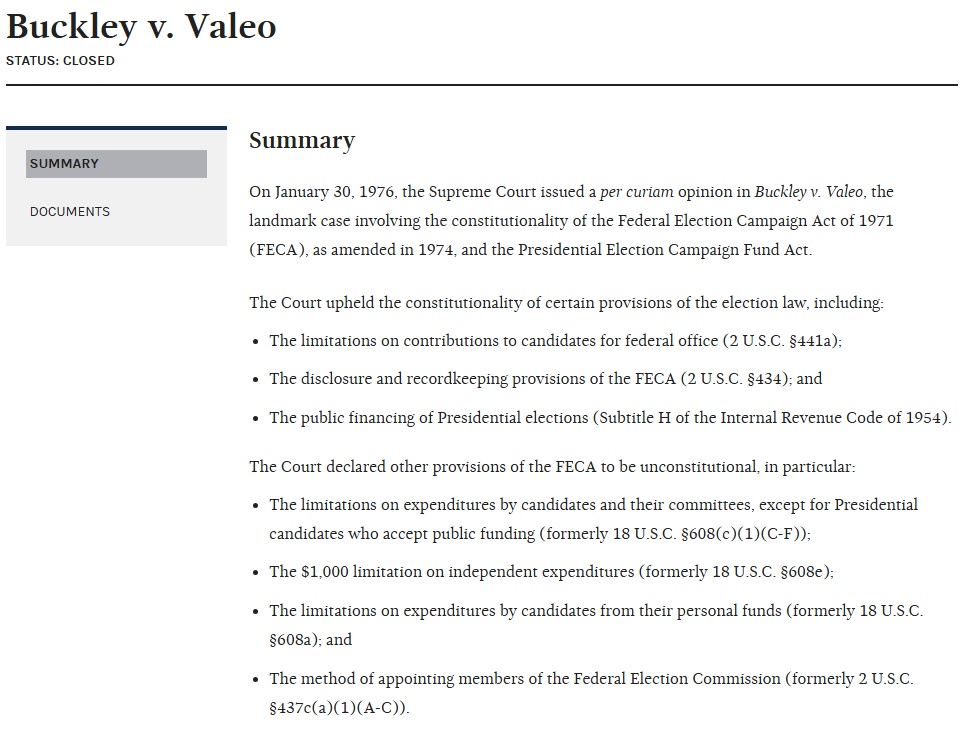

This FEC legal summary of Buckley v. Valeo highlights the Court’s central framework: contribution limits can be justified as anti-corruption measures, but expenditure limits were treated as much more direct restraints on political speech. The image is useful for anchoring class notes in a specific landmark holding that continues to structure modern campaign-finance doctrine. It reinforces why many disputes recur in litigation over tailoring and burdens on speech and association. Source

The strength of the governmental interest (especially preventing corruption)

Whether a law is narrowly tailored or overly burdensome on speech and association

Whether the regulated activity is closer to expressive political advocacy or to direct influence over candidates and officeholders

Because the Constitution sets boundaries on what government may restrict, campaign finance policy is shaped by an ongoing push-and-pull among Congress, state legislatures, regulators, and judicial review.

Why the debate persists

The controversy remains unresolved because it reflects competing democratic values that are both widely supported:

Liberty: robust freedom to advocate, spend, and organise politically

Integrity: preventing corruption and preserving trust in elections

Fairness: ensuring elections are competitive and broadly representative

Campaign finance laws and court cases therefore continue to evolve as new technologies, fundraising methods, and political strategies test the line between regulation and protected political speech.

FAQ

Disclosure is justified as voter information and anti-corruption transparency, but critics argue it can chill speech through harassment or retaliation. Courts often assess whether burdens are proportional to informational benefits.

Public confidence affects legitimacy and compliance. Even without proven quid pro quo, widespread belief that money buys influence can depress participation and trust, which lawmakers cite to justify regulation.

Speaker-based rules target who may spend (individuals, groups, entities). Content-based rules target what may be said. The latter is typically viewed as more constitutionally suspect in U.S. free speech doctrine.

Small-dollar platforms and rapid micro-donations blur lines between grassroots participation and mass influence. Regulators face challenges around verification, cross-state activity, and identifying coordinated spending online.

Rules can shift money into less transparent channels, encourage workarounds, or advantage actors best able to hire compliance experts. Reforms may also change incentives for candidates’ time use and messaging.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one argument that campaign finance limits are necessary in U.S. elections.

1 mark: Identifies a valid argument (e.g., preventing quid pro quo corruption or the appearance of corruption).

1 mark: Explains how limits reduce that problem (e.g., reducing donor leverage or preferential access).

(6 marks) Evaluate the claim that restricting political spending violates the First Amendment more than it protects democracy.

2 marks: Explains the free speech/association argument (spending enables dissemination of political messages; government restriction burdens political advocacy).

2 marks: Explains the pro-regulation democratic protection argument (preventing corruption/appearance; protecting political equality or public trust).

2 marks: Evaluation with a justified judgement (weighs competing values, notes trade-offs, and reaches a defensible conclusion).