AP Syllabus focus:

‘Media use of polling to show trust or confidence can turn elections into “horse races,” emphasizing popularity over qualifications and platforms.’

Election coverage shapes what voters notice and how they interpret campaigns. Polling-driven reporting can clarify trends, but it can also narrow attention to who is winning rather than what candidates propose.

How polling becomes “news” in election coverage

What polls measure (and what they do not)

Public opinion polls are used by media outlets to signal trust, confidence, and likely electoral outcomes. Poll results are often treated as events (“Candidate X surges”) rather than as imperfect measurements of opinion at a given time.

Public opinion poll: A survey of a sample of individuals used to estimate the attitudes or preferences of a broader population (such as likely voters).

Because polls estimate rather than count, coverage is heavily influenced by methodological choices (such as who is contacted and which voters are considered “likely”).

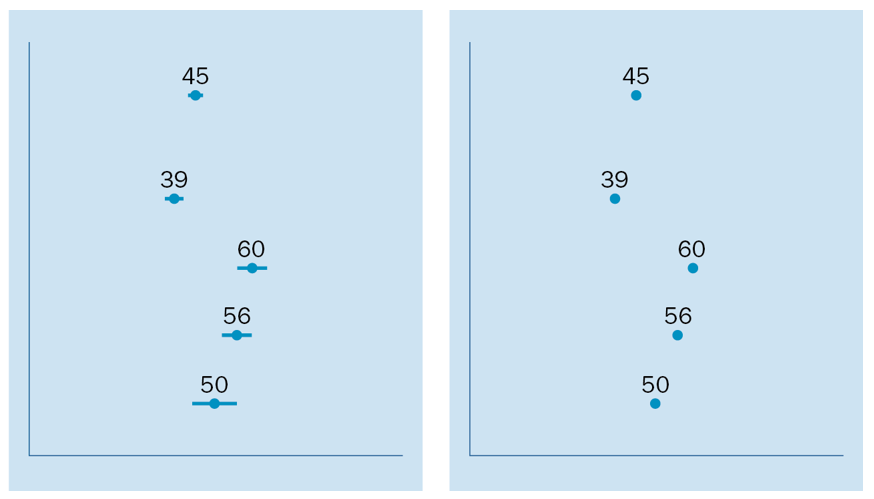

Side-by-side example charts showing the same subgroup poll estimates with (left) and without (right) 95% confidence-interval error bars. The figure highlights how visualizing uncertainty can prevent readers from over-interpreting small differences as meaningful changes in public opinion. Source

Why “trust or confidence” becomes a headline metric

Media frequently translate complex attitudes into simple indicators:

Approval/favourability as a stand-in for “candidate quality”

Head-to-head vote choice as a proxy for “electability”

Momentum narratives based on small shifts over time

This framing can make elections feel like a continuous scoreboard, even when the underlying changes are within a poll’s typical uncertainty.

“Horse race” narratives and their effects

Horse race framing

“Horse race” coverage focuses on who is ahead, who is behind, and strategic implications (ad buys, debate “wins,” turnout operations), often at the expense of policy comparison.

Horse race journalism: Election reporting that emphasises polling, strategy, and competitiveness—who is winning and why—more than candidates’ qualifications, governing records, or issue positions.

Horse race framing aligns closely with the syllabus emphasis: media use polling to show trust or confidence and can turn elections into “horse races,” emphasising popularity over qualifications and platforms.

Common media techniques that intensify horse race coverage

Reporting rankings (first/second/third) instead of substantive issue differences

Using trendlines (“surge,” “collapse”) without contextualising uncertainty

Highlighting electability arguments (“can they win?”) as a dominant criterion

Treating campaigns as strategy games: “path to victory,” “base turnout,” “swing voters”

Potential consequences for voters and campaigns

Polling-centred narratives can shape behaviour and information priorities:

Issue displacement: Voters learn less about platforms, trade-offs, and policy feasibility.

Strategic voting pressures: Some voters prioritise “beating the other side” over preferred policies.

Bandwagon/underdog dynamics: Perceptions of momentum can influence enthusiasm, donations, and volunteering, even if actual persuasion is limited.

Candidate incentives: Campaigns may chase favourable coverage by optimising for optics, “media moments,” and polling bumps rather than long-term governance arguments.

Interpreting polling coverage critically

Key questions students should ask when media cite polls

Who was surveyed? Adults, registered voters, or likely voters?

How was it conducted? Phone, online panels, mixed methods?

When was it fielded? Before/after major events (debates, scandals, crises)?

What is the question wording? Subtle wording shifts can change responses.

Is it one poll or an average? Single polls are noisier than aggregated trends.

How polling can still inform democratic choice

Polling is not inherently harmful; it can support accountability when used carefully:

Identifying public priorities that candidates address or ignore

Revealing polarisation or cross-pressures in the electorate

Testing whether campaign claims are resonating across groups

The central trade-off is informational: the more coverage fixates on competitive standing, the less space remains for qualifications, governing capacity, and platform comparison.

FAQ

They often apply informal screens (pollster reputation, sample size, recency) and editorial judgement.

Some also prefer aggregated models to reduce outlier influence, though standards vary by outlet.

A polling average combines multiple polls to estimate overall standing.

It is used to smooth random variation, but it can still reflect shared biases if many polls use similar assumptions.

Because narratives reward novelty and conflict.

Small changes can be within normal measurement noise, yet they provide a storyline that is easier to package than policy analysis.

Perceived competitiveness can trigger strategic giving and activism.

Front-runners may attract “inevitable winner” resources

Trailing candidates may see drops—or mobilisation if framed as an underdog surge

Reporting results describes measured preferences.

Poll-driven strategy coverage interprets what campaigns “should do” (message shifts, turnout tactics), which can crowd out discussion of platforms and governing priorities.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one way that media use of polling can encourage “horse race” election coverage.

1 mark: Identifies a relevant mechanism (e.g., reporting who is ahead/behind using polls).

1 mark: Explains how this shifts attention towards popularity/competitiveness rather than platforms/qualifications.

(6 marks) Analyse two distinct effects of horse race narratives based on polling on (i) voter information and (ii) campaign strategy.

1 mark: Identifies an effect on voter information (e.g., reduced policy knowledge, issue displacement).

2 marks: Develops that effect with clear linkage to polling-driven coverage.

1 mark: Identifies an effect on campaign strategy (e.g., prioritising optics, targeting “winnability,” chasing momentum).

2 marks: Develops that effect with clear linkage to polling headlines/competitive framing.