AP Syllabus focus:

‘Consumer-driven outlets and emerging technologies can reinforce existing beliefs, while uncertainty about credibility affects trust in news and information.’

Digital media have transformed how Americans encounter political information. Personalised platforms can narrow exposure to diverse views, while misinformation and uncertain sourcing raise doubts about what is true, shaping participation and democratic accountability.

Technology and the modern information environment

Consumer-driven outlets and personalisation

Modern media are increasingly consumer-driven: audiences actively choose what to watch, read, and share, rather than receiving a common set of news from a few outlets.

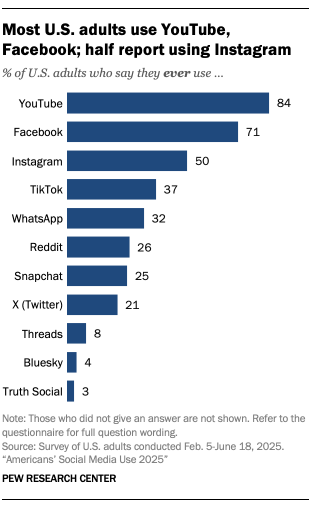

Bar chart data from Pew Research Center showing the share of U.S. adults who use major social media platforms (with YouTube and Facebook highest, and smaller shares for Instagram, TikTok, Reddit, and others). In a consumer-driven environment, these platform choices structure what political content people are likely to encounter in the first place. The figure is useful for connecting “high-choice” media conditions to downstream effects like selective exposure and polarization. Source

Many platforms use algorithmic curation to personalise content based on prior behaviour (clicks, likes, watch time), which can unintentionally intensify political bias and polarisation.

Personalisation incentives: platforms often prioritise content likely to keep users engaged.

Low distribution costs: anyone can publish widely, enabling faster political communication but also more unverified claims.

Microtargeting: campaigns, groups, and creators can tailor messages to narrow audiences, sometimes reducing shared civic understanding.

Emerging technologies that shape political communication

“Emerging technologies” includes tools and systems that change how information is produced and circulated, such as recommendation algorithms, automated accounts, and AI-generated media.

Automation: bots and coordinated accounts can amplify narratives, create the illusion of consensus, or harass critics.

Synthetic media: AI-edited images, audio, or video can blur the line between authentic and manipulated content.

Frictionless sharing: reposting and short-form clips enable rapid spread of simplified or context-free political messages.

Echo chambers and reinforcement of beliefs

Echo chamber: a media environment in which individuals are primarily exposed to information and opinions that reflect and reinforce their existing beliefs.

Echo chambers do not require explicit censorship; they can result from the interaction of user choice, social networks, and algorithmic recommendations. Over time, reinforcement can increase certainty, reduce openness to counterarguments, and heighten negative views of political out-groups.

Mechanisms that produce echo chambers

Selective exposure: people are more likely to choose sources aligned with their ideology or party identification.

Homophily in networks: users often connect with like-minded friends, influencers, or communities.

Engagement-based ranking: emotionally arousing content (anger, fear, moral outrage) can receive disproportionate reach.

Social signalling: sharing partisan content can communicate identity and loyalty, encouraging repeated exposure.

Consequences for democratic debate

Echo chambers can affect the quality of democratic deliberation by narrowing the “common set of facts” needed for productive disagreement.

Reduced cross-cutting exposure: fewer encounters with opposing viewpoints can limit understanding of alternative policy arguments.

Polarisation dynamics: repeated reinforcement can strengthen ideological consistency and increase hostility toward compromise.

Agenda distortion: highly engaged niche communities can elevate issues that feel urgent within the group but are less salient to the broader public.

Credibility concerns and trust in political information

Uncertainty about credibility

The syllabus emphasis is that uncertainty about credibility affects trust in news and information. Credibility problems emerge when audiences cannot easily judge whether a claim is accurate, fairly presented, or produced by reliable actors.

Credibility: the perceived trustworthiness and expertise of a source or piece of information.

A fragmented environment can weaken shared standards for verification. When misinformation is common—or when claims of “fake news” are used broadly—citizens may distrust not only false sources but also legitimate journalism and institutions.

Sources of credibility breakdown

Misinformation vs. disinformation

Misinformation: inaccurate information shared without intent to deceive.

Disinformation: deliberately false information spread to mislead or manipulate.

Source ambiguity: viral posts may lack clear authorship, evidence, or editorial accountability.

Manipulated context: real images or quotes can be presented with misleading captions or selective edits.

Speed over verification: competitive pressure to post quickly can reduce careful fact-checking.

Declining gatekeeping: fewer common “filters” means more unvetted information reaches mass audiences.

Effects on political behaviour and democratic accountability

Credibility concerns can change how people participate and how effectively they can hold leaders accountable.

Lower institutional trust: scepticism toward media, elections, or public agencies can reduce acceptance of shared outcomes.

Confident misperceptions: repeated exposure can make false claims feel familiar and therefore “true.”

Cynicism and withdrawal: if citizens believe “nothing is trustworthy,” they may disengage from politics.

Vulnerability to manipulation: uncertain information environments can be exploited by domestic actors or foreign influence efforts to deepen division.

Evaluating information in a high-choice media system

Practical credibility indicators (without guaranteeing truth)

Students should understand common cues people use to assess credibility, and their limits.

Transparency: clear author identity, sourcing, and corrections policies.

Evidence quality: use of data, documents, or named experts rather than anonymous assertions.

Corroboration: whether multiple independent outlets report the same core facts.

Incentives and accountability: professional standards, reputational costs, and editorial oversight.

These indicators matter because consumer-driven environments often prioritise attention, not accuracy, and the burden of evaluation shifts to individuals.

Why echo chambers and credibility concerns reinforce each other

When people distrust opposing sources, they may retreat further into aligned communities, deepening echo chambers. Conversely, echo chambers can heighten suspicion of outside information by framing it as biased or hostile. Together, these dynamics can reshape democratic debate by reducing shared factual baselines while increasing confidence within partisan information bubbles.

FAQ

They often combine browsing data, social network analysis, and content classification.

Common approaches include:

measuring the ideological slant of sources a user consumes

mapping whether a user’s network contains cross-partisan ties

testing exposure diversity over time rather than a single day’s activity

Measures vary, and “some exposure to opposing views” does not necessarily mean meaningful engagement.

Source credibility focuses on who is speaking (expertise, trustworthiness, accountability).

Message credibility focuses on the claim itself (evidence, logic, consistency with verified facts).

A credible source can share an inaccurate message, and an unreliable source can sometimes share accurate information, so separating the two helps evaluation.

It can increase the overall volume of plausible-looking political content, making verification harder.

Even with labels:

reposts may remove context

audiences may not see the label on cropped clips

constant exposure can normalise doubt, encouraging “nothing is real” cynicism

Design affects what people notice and trust.

Examples:

ranking systems that reward engagement can elevate sensational claims

prompts that encourage resharing can spread low-quality information

verification badges and identity checks can raise accountability, but may be unevenly applied

Small interface changes can shift behaviour at scale.

Yes, sometimes.

Reasons include:

identity-protective reasoning (rejecting corrections seen as threatening group identity)

“continued influence” effects (initial misinformation remains memorable)

distrust of fact-checkers perceived as partisan

More effective corrections tend to be specific, evidence-based, and repeated across trusted sources.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Define an echo chamber and explain one way emerging technologies can contribute to it.

1 mark: Correct definition of echo chamber (exposure mainly to reinforcing views).

1 mark: Identifies a relevant technology mechanism (e.g., algorithms, microtargeting, bots).

1 mark: Explains the link (e.g., recommendations show similar content repeatedly, reducing cross-cutting exposure).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Analyse how uncertainty about credibility in a consumer-driven media environment can affect democratic debate and political participation in the United States.

1 mark: Identifies that credibility uncertainty reduces trust in news/information.

1–2 marks: Explains effects on democratic debate (e.g., weaker shared facts, increased polarisation, reduced compromise).

1–2 marks: Explains effects on participation (e.g., disengagement/cynicism, susceptibility to manipulation, mobilisation based on misinformation).

1 mark: Uses clear causal reasoning linking consumer choice/personalisation to credibility problems (e.g., fragmented sources, reduced gatekeeping).