AP Syllabus focus:

‘States choose how to allocate electors; most use winner-take-all. Because outcomes can differ from the national popular vote, the Electoral College is debated.’

Because the Constitution leaves elector allocation largely to the states, presidential outcomes depend on state rules, not just national vote totals. This creates recurring debates about fairness, representation, and potential reforms.

How states allocate electors

States have broad authority (through state law) to decide how their electoral votes are awarded, as long as they appoint electors by Election Day and follow federal constitutional constraints.

Winner-take-all (the dominant rule)

Most states use a statewide “unit rule” that awards all electors to the statewide popular vote winner.

Winner-take-all (unit rule): A statewide allocation method where the candidate who wins the most votes in a state receives all of that state’s electoral votes (not required by the Constitution).

This method magnifies narrow statewide victories into large electoral vote gains, shaping campaign incentives and the meaning of “winning” a state.

Alternatives used or proposed

A small number of states use, or have considered using, methods that split electors.

District method (used in Maine and Nebraska)

One elector awarded to the winner of each congressional district

Two statewide electors awarded to the statewide winner

Proportional allocation (common proposal, rarely adopted)

Electors would be awarded roughly in proportion to each candidate’s share of the statewide vote

Would reduce “all-or-nothing” outcomes but raises design questions (rounding rules, thresholds, and whether to require a minimum vote share)

Why outcomes can differ from the national popular vote

The syllabus emphasises that “outcomes can differ from the national popular vote,” which is central to debates over legitimacy and reform. Mismatches can occur when a candidate:

Wins large margins in some states (piling up “excess” votes that do not change elector totals), but

Loses narrowly in enough other states to fall short in the Electoral College

Because electoral votes are awarded state-by-state (and usually winner-take-all), the system rewards the geographic distribution of support, not simply the national total.

Major debates over reform

Arguments tend to cluster around competing democratic values: majority rule, federalism, and political stability.

Critiques that drive reform proposals

Legitimacy concerns: A “popular vote winner” can lose the presidency, leading critics to question democratic responsiveness.

Battleground focus: Winner-take-all encourages campaigns to prioritise competitive “swing states,” potentially ignoring safe states.

Vote weight differences: Because each state has two electors tied to Senate representation, smaller states can have slightly greater electoral vote per resident than larger states.

Polarisation and incentives: Candidates may tailor messages to decisive state coalitions rather than building broad national majorities.

Defences that resist reform

Federalism rationale: The presidency is chosen through states as political units, reinforcing the role of states in national elections.

Broad coalition argument: Candidates must assemble support across multiple states/regions rather than concentrating votes in a few populous areas.

Stability: Winner-take-all can produce clearer outcomes and reduce the frequency of nationwide recount disputes (though it can increase the stakes of recounts in pivotal states).

Reform pathways and constraints

Different reforms vary in feasibility and constitutional difficulty.

Constitutional amendment options

Abolish the Electoral College in favour of a national popular vote

Require proportional allocation or a uniform national allocation rule

Amendments face high barriers because they require supermajority support, and states benefiting from the current system may oppose change.

State-based reforms (no amendment required)

Adopting the district method or proportional allocation through state legislation

Binding electors more tightly through state laws to reduce uncertainty about elector behaviour

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC): An agreement among participating states to award their electors to the national popular vote winner once the compact includes states totaling at least 270 electoral votes.

Even state-based reforms create debate about constitutional interpretation, partisan incentives, and whether changes would produce unintended consequences (for example, shifting campaign attention to different types of competitive areas).

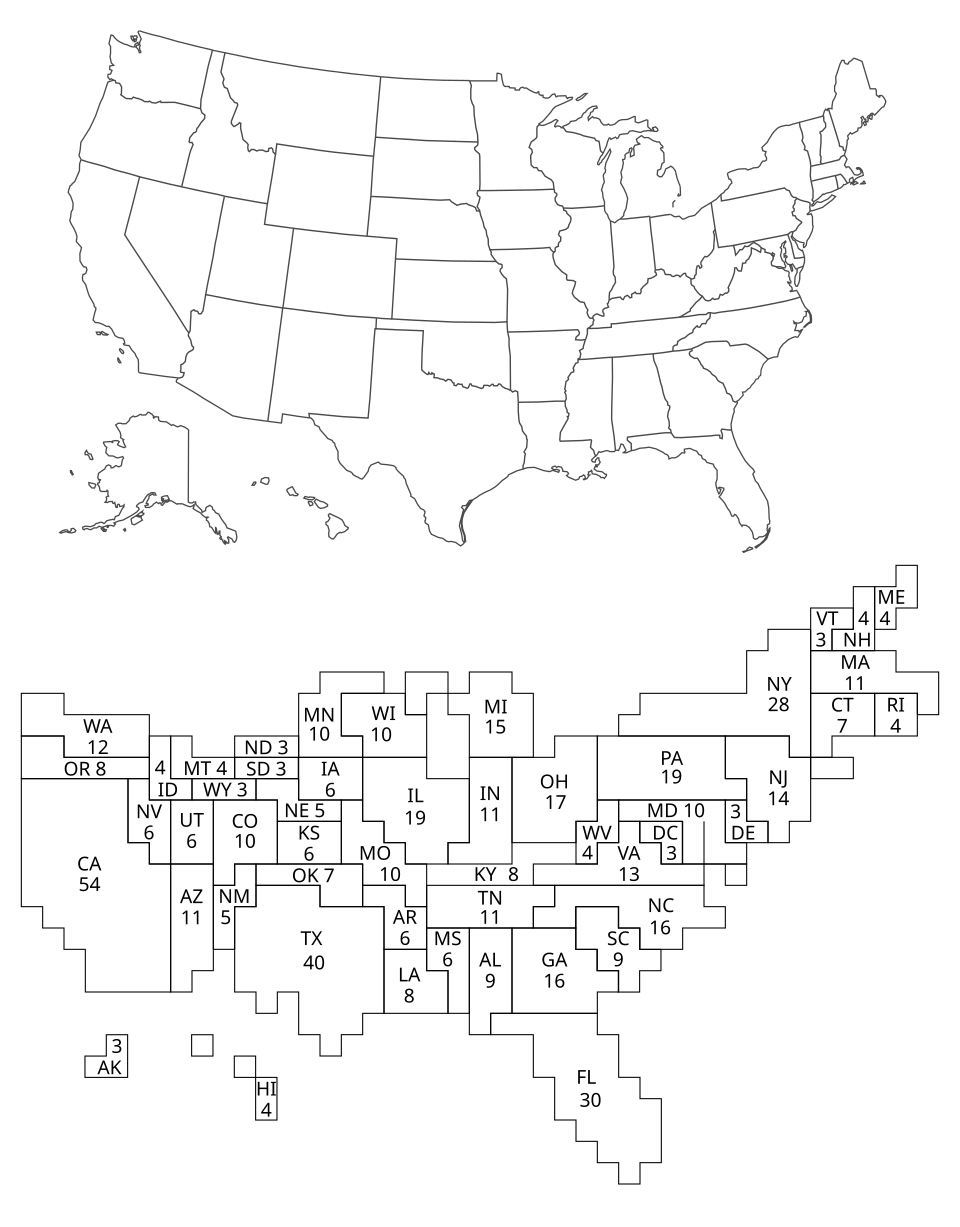

This cartogram depicts the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) using electoral votes as the unit of measurement (each square represents one electoral vote). It visually reinforces the rule that the compact only takes effect once participating jurisdictions collectively reach the 270-electoral-vote threshold needed to guarantee the national popular vote winner an Electoral College majority. Source

FAQ

Possibly, but it is contested.

It would raise disputes over Article II state power versus congressional power to regulate elections, likely triggering Supreme Court review.

Design choices matter.

Thresholds (e.g., 5%) could limit fragmentation

Without thresholds, splitting electors could increase the chance no candidate reaches 270

Because many congressional districts are not competitive.

The two statewide electors also often match the statewide winner, reducing split outcomes.

States can change election laws, but timing is constrained.

Late changes may face litigation, federal “safe harbour” deadlines, and political backlash over perceived manipulation.

Compact terms govern withdrawal, but a late exit would be controversial.

It could produce court challenges over contract-like obligations and the constitutionality of interstate compacts without explicit congressional consent.

Practice Questions

Explain one way that winner-take-all allocation can affect campaign strategy. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies an effect of winner-take-all (e.g., focus on swing states, neglect safe states, targeted advertising/visits).

1 mark: Explains why (because only the statewide plurality matters for gaining all electors, marginal votes in competitive states are most valuable).

Evaluate two arguments for reforming how electors are allocated, and one argument against reform. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks: Argument for reform #1 (1 for stating, 1 for linking to popular-vote/representation concerns).

Up to 2 marks: Argument for reform #2 (1 for stating, 1 for linking to battleground bias/vote equality/legitimacy).

Up to 2 marks: Argument against reform (1 for stating, 1 for linking to federalism, coalition-building, or stability/clear outcomes).