AQA Specification focus:

‘How supply-side policies can help to achieve supply-side improvements in the economy.’

Supply-side policies are essential for long-term economic growth. They aim to improve productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness, directly strengthening aggregate supply and potential output in an economy.

Understanding Supply-Side Policies

Supply-side policies are measures designed to increase the productive capacity of the economy by improving how efficiently resources are used. Unlike demand-side policies, which focus on short-term changes in aggregate demand, supply-side policies aim to influence long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) and the underlying trend rate of growth.

Supply-side policies: Government strategies aimed at improving the efficiency and productivity of markets to expand the economy’s potential output.

How Policies Deliver Improvements to Aggregate Supply

Supply-side improvements are achieved when these policies lead to:

Enhanced productivity of labour and capital.

Increased efficiency in resource allocation.

Higher labour market participation through better incentives.

Greater innovation and investment in new technologies.

Such improvements shift the LRAS curve to the right, signalling a larger potential output without generating inflationary pressure.

Key Channels of Supply-Side Improvements

1. Education and Training

Improving the skills and knowledge of workers increases labour productivity. Higher levels of human capital allow workers to contribute more effectively, boosting long-term output.

Human capital: The stock of skills, knowledge, and experience possessed by individuals that increases their productive potential.

Education policy, apprenticeships, and vocational training all help reduce structural unemployment while raising overall economic efficiency.

2. Taxation and Incentives

Tax policy can be structured to encourage work, saving, and investment:

Lowering income tax rates can increase labour supply by making work more attractive relative to leisure.

Reducing corporation tax encourages business investment in capital and innovation.

Offering tax relief on research and development stimulates technological progress.

These incentives improve both short-term competitiveness and long-term growth capacity.

3. Labour Market Reforms

Rigid labour markets can hinder growth. Reforms may include:

Reducing trade union power to allow more flexible wage-setting.

Improving job matching services to lower frictional unemployment.

Encouraging flexible contracts to increase mobility and adaptability.

Such reforms enhance efficiency and ensure resources are allocated where they are most productive.

4. Infrastructure Investment

Government investment in infrastructure, such as transport, digital networks, and energy systems, improves the efficiency of economic activity. Well-developed infrastructure lowers costs for firms and facilitates higher productivity in the long run.

5. Promoting Competition and Innovation

Policies such as deregulation and privatisation reduce barriers to entry, encouraging competition. Competitive markets drive firms to innovate, improve efficiency, and lower prices, ultimately raising aggregate supply.

6. Encouraging International Trade

Free trade agreements and reduced tariffs increase exposure to global competition. This not only provides access to cheaper imports and larger export markets but also stimulates domestic firms to become more efficient.

Free-Market vs Interventionist Supply-Side Policies

Supply-side policies can be broadly categorized into free-market and interventionist approaches.

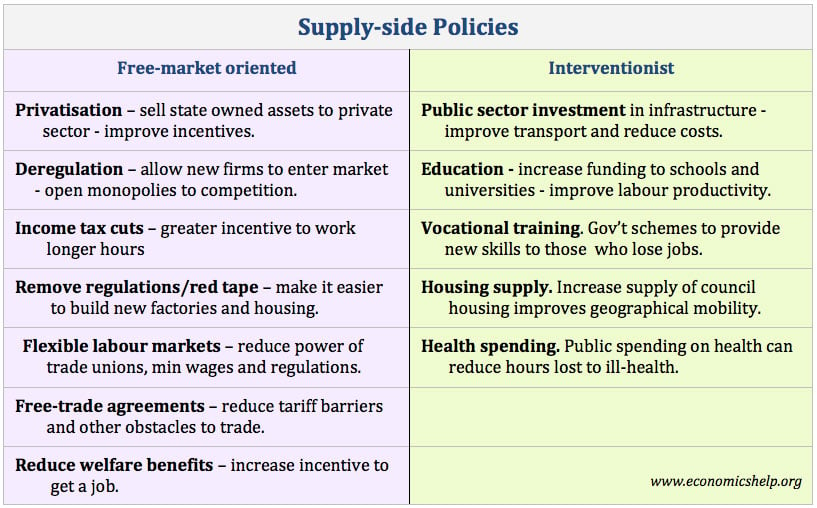

This chart contrasts free-market and interventionist supply-side policies, highlighting their respective strategies and objectives in enhancing economic efficiency and productivity. Source

Free-Market Approaches

Policies that reduce government intervention in markets aim to let competitive forces improve efficiency naturally. Examples include:

Tax cuts to stimulate incentives.

Deregulation to reduce business costs.

Privatisation to encourage competition.

Interventionist Approaches

Government plays a direct role in correcting market failures and supporting growth. Measures include:

Investment in public education and healthcare.

Subsidies for R&D to overcome underinvestment.

Industrial policy to support key strategic sectors.

Both approaches can deliver supply-side improvements, though their effectiveness may depend on the structure of the economy and institutional context.

Macroeconomic Outcomes of Supply-Side Improvements

Supply-side policies that successfully raise potential output can deliver several important macroeconomic benefits:

Sustained economic growth by raising the trend rate of growth.

Lower inflationary pressure, as higher supply capacity meets demand without pushing up prices.

Improved balance of payments, as greater competitiveness boosts exports.

Reduced unemployment, particularly structural and frictional forms.

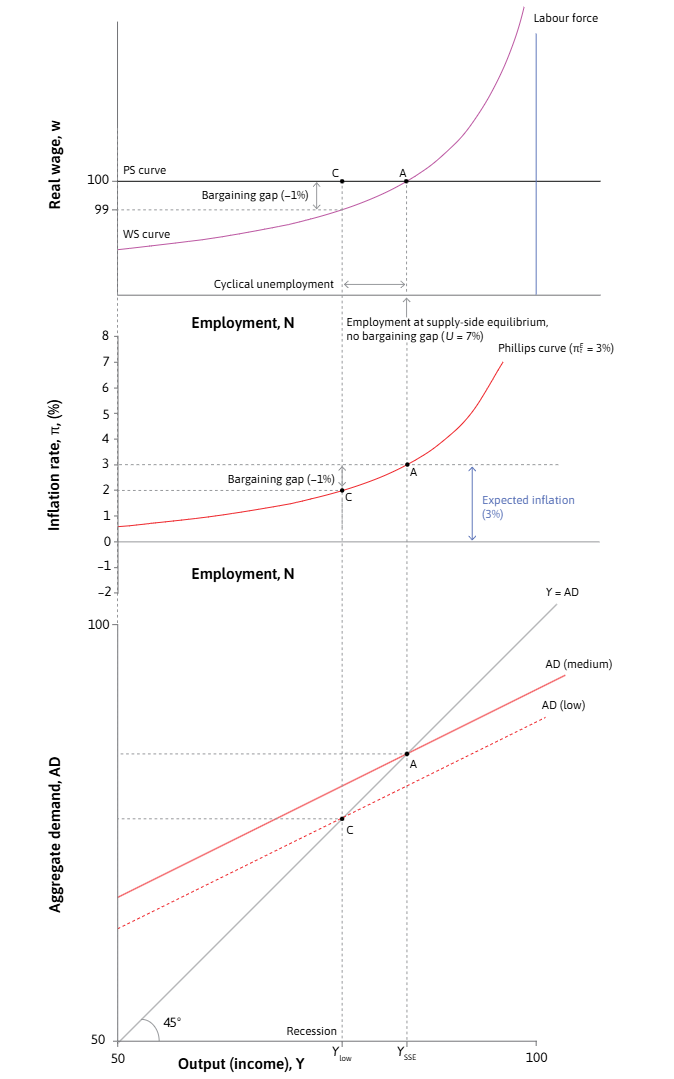

Supply-side policies can lead to lower unemployment and stable inflation rates by increasing the economy's productive capacity.

This diagram depicts the potential effects of supply-side policies on unemployment and inflation, demonstrating how enhancing productive capacity can lead to lower unemployment and stable inflation. Source

Microeconomic Effects

While the focus is on long-run aggregate supply, these policies also have significant microeconomic impacts:

Enhanced firm efficiency and productivity.

Greater consumer choice due to increased competition.

More efficient allocation of resources across industries.

These micro-level changes underpin the macro-level improvements and ensure long-term sustainability of growth.

Linking Policies to Supply-Side Improvements

The key to understanding this subsubtopic is recognising that policies must deliver tangible improvements in efficiency, productivity, and innovation for the economy to achieve genuine supply-side gains. Without improvements, policy changes risk being ineffective or misdirected.

FAQ

Supply-side policies are deliberate government interventions, such as tax cuts or investment in training, aimed at boosting productive capacity.

By contrast, natural supply-side improvements arise without government involvement, often from private-sector innovation, productivity gains, or long-term technological change.

Education and training enhance the quality of the workforce, directly raising labour productivity.

They also reduce skills mismatches in the labour market, helping lower structural unemployment.

In the long run, a better-skilled workforce supports sustained economic growth and competitiveness.

Tax incentives encourage desirable economic behaviour, such as increased work effort, saving, or business investment.

Examples include:

Lower income tax to encourage higher labour supply.

Reduced corporation tax to promote investment.

R&D tax credits to support innovation.

The impact of supply-side policies often relies on structural changes, which are gradual.

For example, investment in education takes years before new graduates enter the workforce, and infrastructure projects can span decades.

This means their full benefits may only be felt in the long term, unlike demand-side measures.

Yes, by increasing aggregate supply, these policies reduce cost pressures in the economy.

An outward shift in LRAS allows output to rise without causing inflation.

This is particularly important for addressing cost-push inflation, as efficiency gains and productivity growth help stabilise prices.

Practice Questions

Define what is meant by supply-side policies. (2 marks)

1 mark for recognising that supply-side policies are government measures designed to improve efficiency or productivity in the economy.

1 mark for noting that these policies aim to increase the economy’s long-run productive capacity or potential output.

Explain how supply-side policies can help to achieve supply-side improvements in the economy. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for identifying examples of supply-side policies (e.g. education and training, tax incentives, deregulation, infrastructure investment).

Up to 2 marks for explaining how these measures increase productivity, efficiency, or labour market participation.

Up to 2 marks for linking these improvements to an outward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) or to higher potential output.

Maximum 6 marks.