AQA Specification focus:

‘The importance of altruism and perceptions of fairness; behavioural economists question the assumption of traditional economic theory that individuals are rational decision makers who endeavour to maximise their utility, and there are reasons why an individual’s economic decisions may be biased.’

Altruism and fairness play a key role in explaining why individuals deviate from purely rational, self-interested decision-making assumed in traditional economic theory.

Understanding Altruism in Economics

Altruism refers to behaviour motivated by a concern for the welfare of others, often at a cost to oneself. In economic terms, this means that an individual may choose an action that reduces their own monetary or material benefit but improves someone else’s position.

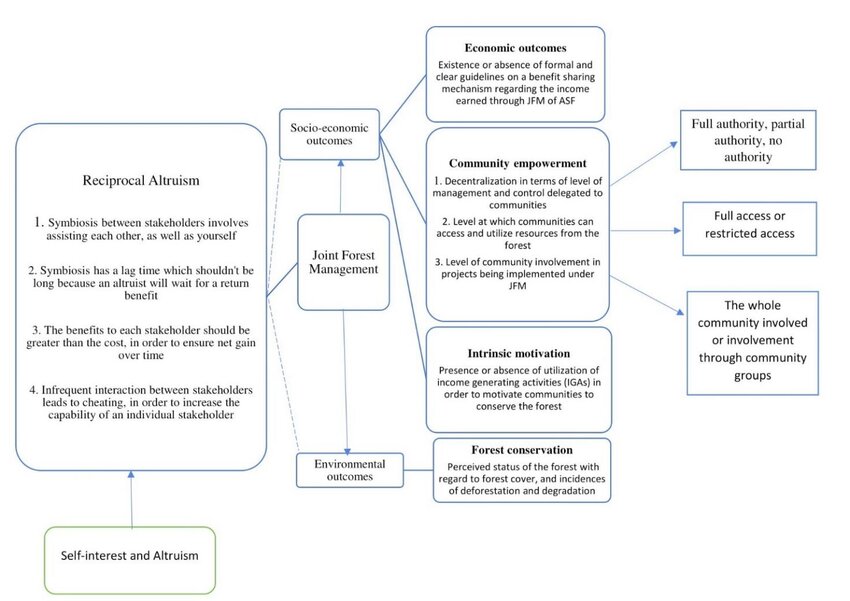

This diagram presents an analytical framework linking reciprocal altruism theory to environmental and socio-economic outcomes, highlighting how altruistic behaviour can influence broader economic dynamics. Source

Altruism: The selfless concern for the well-being of others, leading to actions that may reduce personal gain to help another individual or group.

In traditional models of utility maximisation, altruism is often treated as irrational because it does not strictly maximise the decision-maker’s own utility in monetary or material terms. However, behavioural economics recognises that individuals derive psychological utility from helping others, such as satisfaction, social approval, or moral fulfilment.

Key Drivers of Altruistic Behaviour

Reciprocity: Expectation of mutual benefit in the future.

Warm-glow giving: The positive emotional reward from helping.

Social image: Desire to be seen positively by peers.

Moral duty: Acting in line with personal or societal ethical standards.

Fairness and Economic Decision Making

Fairness influences decision-making by shaping perceptions of what constitutes an acceptable distribution of resources, wages, or opportunities. This can cause deviations from purely rational predictions of classical models.

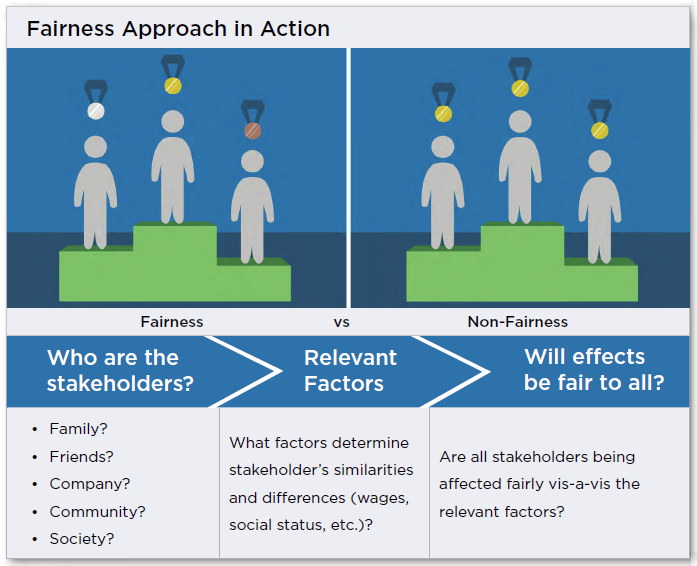

The image contrasts fairness and non-fairness approaches in decision-making, illustrating how perceptions of fairness can influence economic choices beyond self-interest. Source

Fairness: The perception that economic outcomes and processes are just, equitable, and acceptable according to societal or personal norms.

The Role of Fairness in Markets

In wage negotiations, workers may reject offers they see as unfair, even if accepting would increase income.

In pricing, consumers may boycott firms perceived to exploit customers or suppliers.

In supply chains, firms may prioritise ethical sourcing even at higher costs.

The Critique of Full Rationality

Traditional economic theory assumes full rationality, meaning individuals process all available information, weigh all options, and choose the one that maximises personal utility. Behavioural economists argue this is unrealistic due to psychological, social, and informational constraints.

Core Criticisms

Individuals often make decisions based on emotions rather than pure logic.

Social preferences like altruism and fairness override narrow self-interest.

Cognitive limitations prevent perfect information processing.

Full Rationality: The assumption in traditional economics that individuals have unlimited cognitive ability, full information, and always act to maximise self-interest.

Reasons Decisions May Be Biased

Behavioural economists identify several factors that challenge the assumption of full rationality:

Bounded rationality: Limited cognitive resources prevent exhaustive analysis.

Bounded self-control: Difficulty resisting short-term temptations despite long-term costs.

Social influences: Decisions shaped by norms, expectations, and peer behaviour.

Emotional responses: Feelings such as guilt, anger, or empathy influencing choices.

Linking Altruism, Fairness, and Market Outcomes

When altruism and fairness influence decisions, market outcomes can differ from those predicted by classical models:

Public goods provision may increase when individuals voluntarily contribute for collective benefit.

Charitable donations are sustained by altruistic motives even without direct returns.

Price stickiness can arise when firms avoid raising prices to maintain perceived fairness.

Policy Implications

Understanding altruism and fairness allows policymakers to design interventions that align with actual human behaviour:

Progressive taxation may gain public support when framed in terms of fairness.

Charitable giving incentives can encourage prosocial contributions.

Fair trade certifications can influence purchasing choices despite higher prices.

Behavioural Economics Perspective

Behavioural economics integrates psychological and social insights into economic analysis, challenging the view that deviations from self-interest are anomalies. Instead, it sees them as predictable patterns:

Altruistic preferences can be incorporated into utility functions.

Fairness norms can be modelled to explain wage rigidity, bargaining outcomes, and consumer behaviour.

Decision-making biases are not just errors but reflections of human priorities beyond wealth maximisation.

Practical Examples of Altruism and Fairness in Action

The Ultimatum Game: Proposers often offer more than the minimum possible, and responders frequently reject low offers despite personal loss—indicating fairness norms at work.

Disaster relief donations: Individuals contribute time or money without expecting tangible returns.

Corporate social responsibility: Businesses engage in environmentally friendly or socially beneficial actions to uphold fairness and community trust.

In summary, the presence of altruism and fairness undermines the assumption that individuals are purely rational, utility-maximising agents. Behavioural economics shows that these social preferences are central to understanding real-world economic behaviour, shaping both personal decisions and market-level outcomes.

FAQ

Behavioural economists often use controlled experiments such as the Dictator Game or the Ultimatum Game to measure altruistic tendencies.

In these games, participants decide how to split a sum of money between themselves and another person. The amount given away, despite no obligation to do so, is used as an indicator of altruism.

Such experiments help researchers quantify the gap between self-interest predictions and observed generosity.

Yes, fairness norms differ significantly between cultures, influencing economic behaviour.

In collectivist cultures, fairness may emphasise equal distribution and communal benefit. In more individualistic cultures, fairness can be linked to merit or performance.

This means identical economic scenarios can result in different outcomes depending on societal norms and expectations.

Fairness concerns persist because social preferences can override purely profit-maximising motives.

Firms may maintain stable prices to avoid customer backlash.

Employers may offer above-market wages to build loyalty and morale.

Long-term reputation benefits can outweigh short-term profit gains.

These decisions stem from the belief that maintaining perceived fairness creates sustainable relationships.

Altruism involves helping others without expecting anything in return, while reciprocity involves mutual benefit.

Reciprocity can be:

Direct: Helping someone who has helped you before.

Indirect: Helping someone to build a good reputation for future benefits.

Altruism is motivated by selfless concern; reciprocity has a strategic element tied to future advantage.

In negotiations, altruism may lead one party to make concessions purely to benefit the other, even at a personal cost.

Fairness shapes the boundaries of acceptable offers — negotiators may reject deals they see as unfair, regardless of the financial loss.

The combination can produce outcomes where mutual respect and perceived justice take precedence over maximising personal gain.

Practice Questions

Define altruism and explain how it may influence an individual's economic decision-making. (2 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of altruism: Selfless concern for the well-being of others, leading to actions that may reduce personal gain to help others.

1 mark for explaining its influence: Individuals may choose options that benefit others even if it reduces their own material or financial gain.

Using examples, explain how perceptions of fairness can lead to deviations from the predictions of traditional economic theory. (5 marks)

1 mark for recognising that traditional economic theory assumes individuals act to maximise personal utility/self-interest.

1 mark for defining fairness: Perception that outcomes and processes are just and equitable according to societal or personal norms.

Up to 2 marks for explaining how fairness can cause deviations:

Workers rejecting unfair wages despite personal loss.

Consumers avoiding products from firms perceived as unethical.

1 mark for an example linked to fairness influencing behaviour (e.g., wage negotiations, boycotts, ethical sourcing).