AQA Specification focus:

‘Bounded rationality and bounded self-control; biases in decision making: rules of thumb, anchoring, availability and social norms.’

Bounded rationality, bounded self-control, and common biases explain why people often deviate from purely rational economic decisions, influencing individual choices and causing potential market inefficiencies.

Bounded Rationality

Bounded rationality refers to the idea that individuals aim to make rational decisions but face limitations in their ability to process and evaluate all available information.

Bounded Rationality: The concept that decision-makers are limited by cognitive capacity, time constraints, and incomplete information, preventing perfectly rational choices.

People do not have unlimited mental resources, so they rely on simplifying strategies rather than analysing every possible option.

Key factors limiting rationality include:

Incomplete information: Consumers and firms may not have all relevant data to make optimal decisions.

Cognitive limitations: Human brains cannot evaluate all possible outcomes and probabilities simultaneously.

Time constraints: Decisions often need to be made quickly, leaving little scope for deep analysis.

Bounded rationality challenges the traditional economic assumption of fully informed, utility-maximising behaviour, leading to systematic deviations from predicted outcomes.

The Bounded Rationality Diagram depicts how individuals, constrained by cognitive limitations and time, seek satisfactory solutions instead of optimal ones. This visual representation aids in understanding the concept of 'satisficing' in decision-making. Source

Bounded Self-Control

Bounded self-control describes situations where individuals recognise the optimal choice but fail to follow through due to impulses, habits, or lack of willpower.

Bounded Self-Control: The tendency for individuals to make decisions that prioritise short-term gratification over long-term benefit, even when they know it is against their best interest.

Examples in economics include:

Overspending despite a budget plan.

Consuming unhealthy goods (e.g., cigarettes, fast food) despite knowing health risks.

Under-saving for retirement due to preference for present consumption.

Bounded self-control is significant for policymakers, as it suggests interventions like automatic enrolment in pension schemes can improve long-term welfare by countering impulsive tendencies.

Common Biases in Decision Making

Bounded rationality and self-control interact with behavioural biases — systematic patterns of deviation from rational judgement. The AQA specification lists four important ones:

Rules of Thumb (Heuristics)

Rules of thumb are mental shortcuts that simplify decision making.

They can be efficient but may ignore relevant variables.

Example: Always buying the cheapest brand without comparing quality.

They reduce cognitive load but can lead to suboptimal results.

Anchoring

Anchoring occurs when people rely too heavily on the first piece of information (the "anchor") when making decisions.

This anchor influences subsequent judgements, even if it is irrelevant.

Example: An initial high price sets expectations for value, making discounts seem more attractive.

Anchoring affects negotiations, pricing strategies, and wage expectations.

Availability Bias

Availability bias is when individuals judge the probability of events based on how easily examples come to mind.

Recent, vivid, or emotionally charged events are given undue weight.

Example: Overestimating plane crash risk after hearing about a recent accident.

This can lead to misallocation of resources or skewed consumer behaviour.

Social Norms

Social norms are unwritten rules about acceptable behaviour within a group or society.

People often conform to group expectations even if it conflicts with individual preferences.

Example: Purchasing certain goods because peers do so, regardless of personal need.

Social norms can create herd behaviour in markets, such as during speculative bubbles.

Interaction of Biases with Economic Policy

Understanding bounded rationality, self-control, and biases is essential for designing effective economic policies. Policymakers can use behavioural insights to improve outcomes without removing choice.

Possible approaches include:

Default options: Automatically enrolling individuals into beneficial schemes unless they opt out.

Framing effects: Presenting choices in a way that highlights positive aspects of beneficial behaviour.

Education and information: Reducing imperfect information to help counter cognitive limitations.

These behavioural factors illustrate why real-world decision making often diverges from the predictions of traditional models, making them a key area of study in behavioural economics.

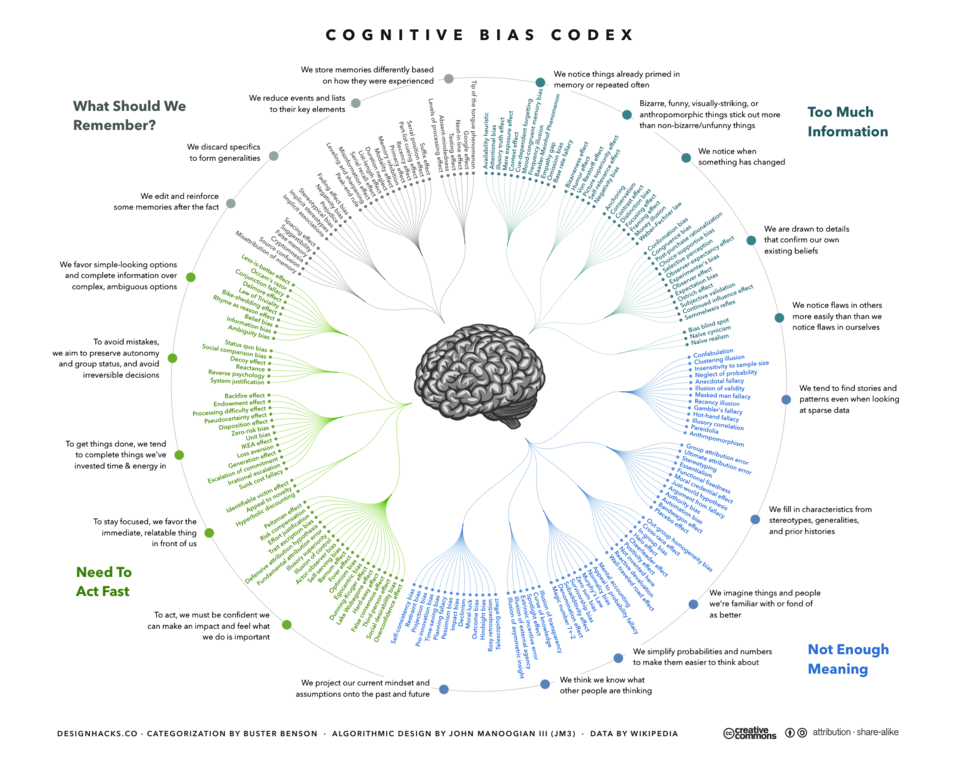

The Cognitive Bias Codex is a detailed map of over 180 cognitive biases, organised into categories like 'Problems with Information Processing' and 'Need to Act Fast'. It highlights biases such as the availability heuristic, anchoring, and social norms, which are crucial for understanding deviations from rational economic behaviour. Source

FAQ

Bounded rationality recognises that individuals still aim to make rational choices, but their decision-making is constrained by limited information, time, and cognitive ability.

Irrational behaviour, however, occurs when choices are made in a way that systematically contradicts logical reasoning or self-interest, often due to emotional influences or strong biases.

Bounded rationality is a limitation within rational decision-making, while irrational behaviour goes beyond these limits and can be entirely inconsistent with rational models.

Yes. Bounded self-control can influence saving rates, investment in education, and healthy lifestyle choices, which all have long-term economic consequences.

For example:

Low saving rates may reduce capital accumulation.

Poor health choices can reduce workforce productivity.

Underinvestment in education can slow innovation and skill development.

Small-scale individual decisions, when widespread, can aggregate into reduced economic growth potential for a country.

Social norms are shaped by cultural values, traditions, and collective attitudes toward conformity.

In collectivist cultures, group harmony and shared expectations are prioritised, making social norms highly influential. In more individualistic cultures, personal choice is emphasised, and norms may have less economic sway.

Government policies, historical traditions, and the role of family or community networks can also strengthen or weaken the impact of social norms on decision-making.

Businesses often design pricing and promotional strategies around predictable biases.

Examples include:

Anchoring: Setting an artificially high original price to make discounts seem more appealing.

Social proof: Using testimonials or “bestseller” labels to encourage herd behaviour.

Scarcity framing: Highlighting limited stock to trigger urgency.

These tactics work because they tap into consumers’ cognitive shortcuts rather than relying solely on rational price and quality evaluation.

Governments can counter availability bias by:

Providing accurate, up-to-date statistical information to replace distorted perceptions.

Running public awareness campaigns to highlight actual risks and probabilities.

Encouraging balanced media coverage that reduces focus on sensational events.

By shifting attention away from recent, vivid examples and toward factual data, policymakers can help the public make better-informed economic choices.

Practice Questions

Define bounded rationality and explain one reason why it may occur. (3 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of bounded rationality: Decision-making is limited by cognitive capacity, incomplete information, and/or time constraints, preventing perfectly rational choices.

1 mark for identifying one reason, e.g., lack of complete information.

1 mark for explanation of how this reason limits rational decision-making.

Explain how two common behavioural biases, identified in behavioural economics, may influence consumer decision-making. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for correctly identifying each bias (max 4 marks). Examples: anchoring, availability bias, rules of thumb, social norms.

Up to 1 mark per bias for explanation of how it influences decisions (max 2 marks).

Anchoring: Initial price influences perceptions of value, even if irrelevant.

Availability bias: Recent or vivid events distort probability judgments, affecting purchase decisions.