AQA Specification focus:

‘It should be understood that not all products that result in positive or negative externalities in consumption are either merit or demerit goods.’

Introduction

Externalities influence markets, but not all goods linked to them can be neatly labelled as merit or demerit goods. Understanding this distinction is essential for accurate economic analysis.

Externalities and Goods

Defining Externalities

Externality: A cost or benefit arising from consumption or production that affects third parties not directly involved in the transaction.

Externalities create a divergence between private costs/benefits and social costs/benefits, often leading to market failure. They are central to understanding why some goods are over-consumed or under-consumed.

Defining Merit and Demerit Goods

Merit Goods: Goods that are judged to be under-consumed if left to the free market, often due to positive externalities or imperfect information.

Demerit Goods: Goods that are judged to be over-consumed if left to the free market, often due to negative externalities or imperfect information.

The classification of merit and demerit goods depends upon a value judgement.

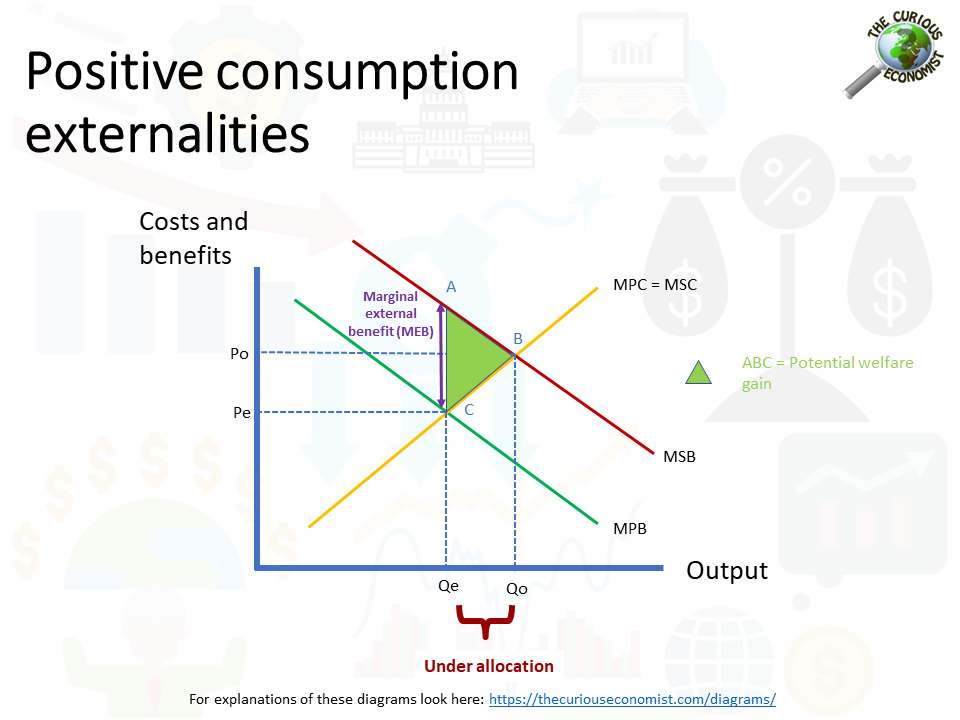

This diagram depicts a positive consumption externality, where the social benefit of consumption exceeds the private benefit, resulting in under-consumption of the good. The area between the MPB and MSB curves represents the external benefit to society. Source

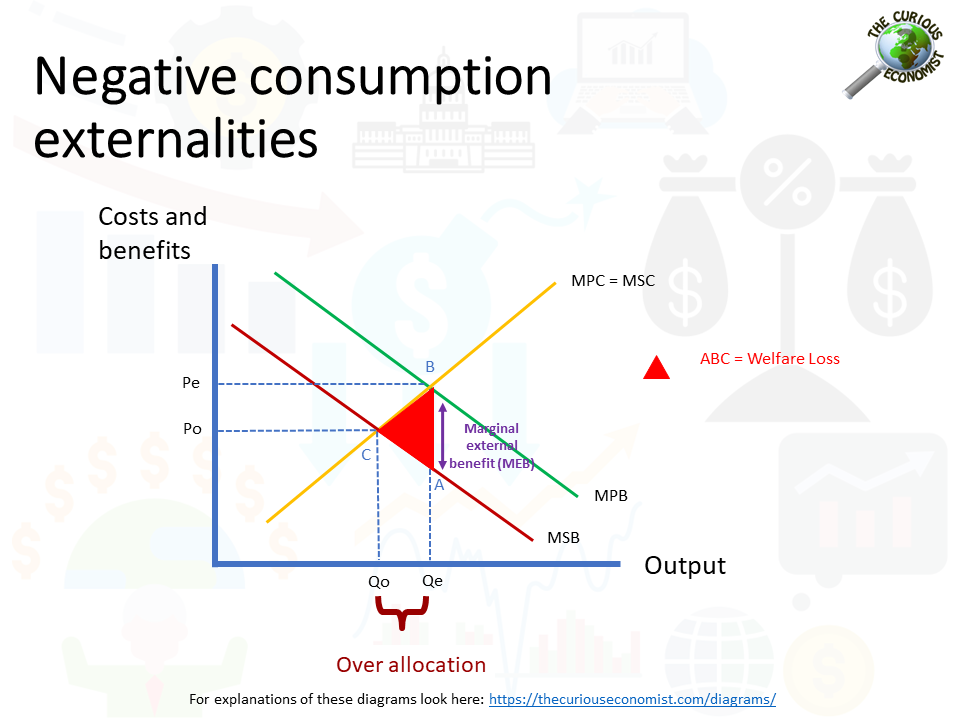

This diagram depicts a negative consumption externality, where the private benefit of consumption exceeds the social benefit, resulting in over-consumption of the good. The area between the MPB and MSB curves represents the external cost to society. Source

Merit and demerit classifications involve value judgements by policymakers and society. However, not every good with externalities neatly fits into these categories.

Why Not All Externality Goods Are Merit or Demerit

Key Distinction

Some goods generate external costs or benefits without society necessarily judging them as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in consumption. The classification of merit or demerit requires more than identifying externalities.

Examples of Goods with Externalities but Not Merit/Demerit

Neighbourhood noise from pets: A dog barking may create a negative externality, disturbing neighbours, yet pets themselves are not classified as demerit goods.

Vaccinations: These generate positive externalities by protecting others, but whether they are defined as merit goods depends on public health priorities and societal values.

Urban architecture: Well-maintained buildings create aesthetic benefits (a positive externality), but they are not automatically categorised as merit goods.

Private car use: Cars generate both negative externalities (pollution, congestion) and positive ones (mobility benefits to society). Their classification is debated and not universally as a demerit good.

The Role of Value Judgements

How Judgements Influence Classification

The distinction between merit/demerit goods and externality goods rests on normative economics:

Merit goods are often linked to desirable social outcomes (e.g. education, healthcare).

Demerit goods are tied to undesirable social behaviours (e.g. smoking, alcohol misuse).

By contrast, goods with externalities can simply create side effects without strong value-based classifications.

Policy Implications

Policymakers may decide to intervene in markets based on whether a good is seen as merit/demerit, not solely because of externalities. This means:

Some externalities result in regulation without reclassification (e.g. noise laws).

Other externalities lead to strong reclassification into merit/demerit goods when moral, social, or health-based value judgements apply.

Analytical Framework

Externalities vs Merit/Demerit Classification

To clarify the distinction, consider:

Step 1: Identify if a good creates an externality (positive or negative).

Step 2: Assess whether society views the consumption as inherently beneficial or harmful beyond the externality.

Step 3: Determine if policy classifies the good as merit (encourage provision) or demerit (discourage consumption).

This framework shows that the existence of an externality is necessary but not sufficient for merit/demerit classification.

Real-World Illustrations

Transport Systems

Public transport generates positive externalities (reduced congestion, lower emissions). It is often classified as a merit good. However, cycling also creates positive externalities, yet bicycles are not universally framed as a merit good — they are simply a mode of transport with spillover benefits.

Housing and Urban Space

A homeowner renovating their property creates positive externalities for neighbours through increased area attractiveness. Yet housing is not broadly classified as a merit good — it is simply a private good with external spillovers.

Technology Use

Smartphone adoption may generate network externalities (benefits increase as more people use them). But smartphones are not defined as a merit good; they remain private goods where externalities exist.

Evaluation of the Specification Requirement

The AQA specification stresses that students must avoid assuming that all externality goods equate to merit or demerit goods. This has three important implications:

It prevents oversimplification of externality analysis.

It highlights the normative nature of classifying goods as merit/demerit.

It encourages awareness that policy intervention depends on societal values, not just economic side effects.

FAQ

An externality good is defined by the presence of spillover effects, either positive or negative, on third parties. These effects occur regardless of whether society views the consumption as good or bad.

Merit or demerit goods, however, require a value judgement, where policymakers or society decide that consumption should be encouraged or discouraged. The key difference lies in the normative judgement, not the existence of an externality.

Classifying every externality good as merit or demerit would oversimplify policy responses and risk excessive intervention.

Some externalities are minor and do not justify government action.

Certain externalities are better addressed through regulation or property rights rather than reclassification.

Societal disagreement often arises on what counts as inherently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ consumption.

Yes, because classification depends on cultural, social, and political values.

For example:

Alcohol may be strongly regulated and treated as a demerit good in some countries, but socially accepted in others.

Vaccination programmes are often viewed as merit goods in developed economies, but in some regions they may not receive the same policy emphasis.

Policy distortion: Resources may be misallocated if every externality leads to heavy intervention.

Loss of neutrality: Economics would shift from analysis towards moral judgement.

Reduced effectiveness: Some externalities, like neighbourhood noise, might be better managed by local rules rather than broad reclassification.

Externalities can change in importance over time, influencing whether goods are reclassified.

Short-term effects may seem minor, but long-term spillovers (like pollution from car use) can shift policy responses.

Changing social norms can transform how goods are judged — smoking was once widely accepted but later redefined as a demerit good due to health externalities.

Practice Questions

Explain why not all goods that create externalities are classified as merit or demerit goods. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that externalities simply represent spillover effects on third parties.

1 mark for recognising that merit/demerit goods require a value judgement about whether consumption is inherently beneficial or harmful.

Discuss, with reference to examples, why some goods that generate externalities are not classified as merit or demerit goods. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Basic understanding of externalities, e.g. defining positive or negative externalities.

1–2 marks: Explanation that classification as merit/demerit involves normative judgements, not just externalities.

1–2 marks: Relevant examples such as pets creating noise (negative externality but not a demerit good), housing improvements creating positive externalities (not necessarily a merit good), or smartphones generating network externalities.

Maximum of 6 marks: Award full marks for clear reasoning supported by at least two appropriate examples and explicit connection to why these are not automatically merit/demerit goods.