IB Syllabus focus:

‘Effective reserves consider target species’ biology, area size/shape, edge effects, and connectivity. UNESCO biosphere reserves use a core, buffer, and transition zones with sustainable management.’

Designing reserves is central to conservation because it determines how effectively biodiversity is protected. Careful planning considers ecological, spatial, and social factors that maintain resilience.

Principles of Reserve Design

When creating or managing reserves, planners aim to maximise biodiversity protection while balancing ecological needs with human pressures.

Target Species’ Biology

The biology of the target species largely determines reserve requirements:

Large predators or migratory species require extensive, connected habitats.

Small, sedentary species may thrive in smaller, isolated patches.

Breeding, feeding, and migration habits must all be considered.

Target Species: A species chosen as the focus of conservation planning, often because of its ecological importance, cultural value, or conservation status.

Understanding reproductive rates, territory sizes, and ecological roles ensures the reserve matches the species’ life history needs.

Reserve Size and Shape

Size: Larger reserves generally support more species and reduce extinction risk.

Shape: Circular reserves are preferred, as they minimise edge effects, whereas elongated or fragmented reserves maximise edge exposure.

Edge Effects: Changes in population or community structures occurring at the boundary of two habitats, often leading to increased predation, invasive species, or microclimatic changes.

Edge Effects and Habitat Fragmentation

Edges alter light, temperature, and humidity, creating conditions that benefit some species but harm others. Key points include:

Narrow reserves with high edge-to-core ratios are more vulnerable.

Invasive species often penetrate from edges, displacing natives.

Interior specialists require deep, undisturbed habitat cores.

Corridors and Connectivity

Corridors connect fragmented reserves, allowing gene flow and species movement. Connectivity reduces risks of inbreeding and local extinctions.

Benefits of corridors include:

Enabling seasonal migration.

Allowing recolonisation after disturbance.

Supporting predator-prey dynamics across landscapes.

Wildlife Corridor: A strip of habitat connecting isolated reserves, allowing movement and genetic exchange between populations.

Corridors must be designed to suit species’ movement patterns and must avoid risks such as road crossings or poaching hotspots.

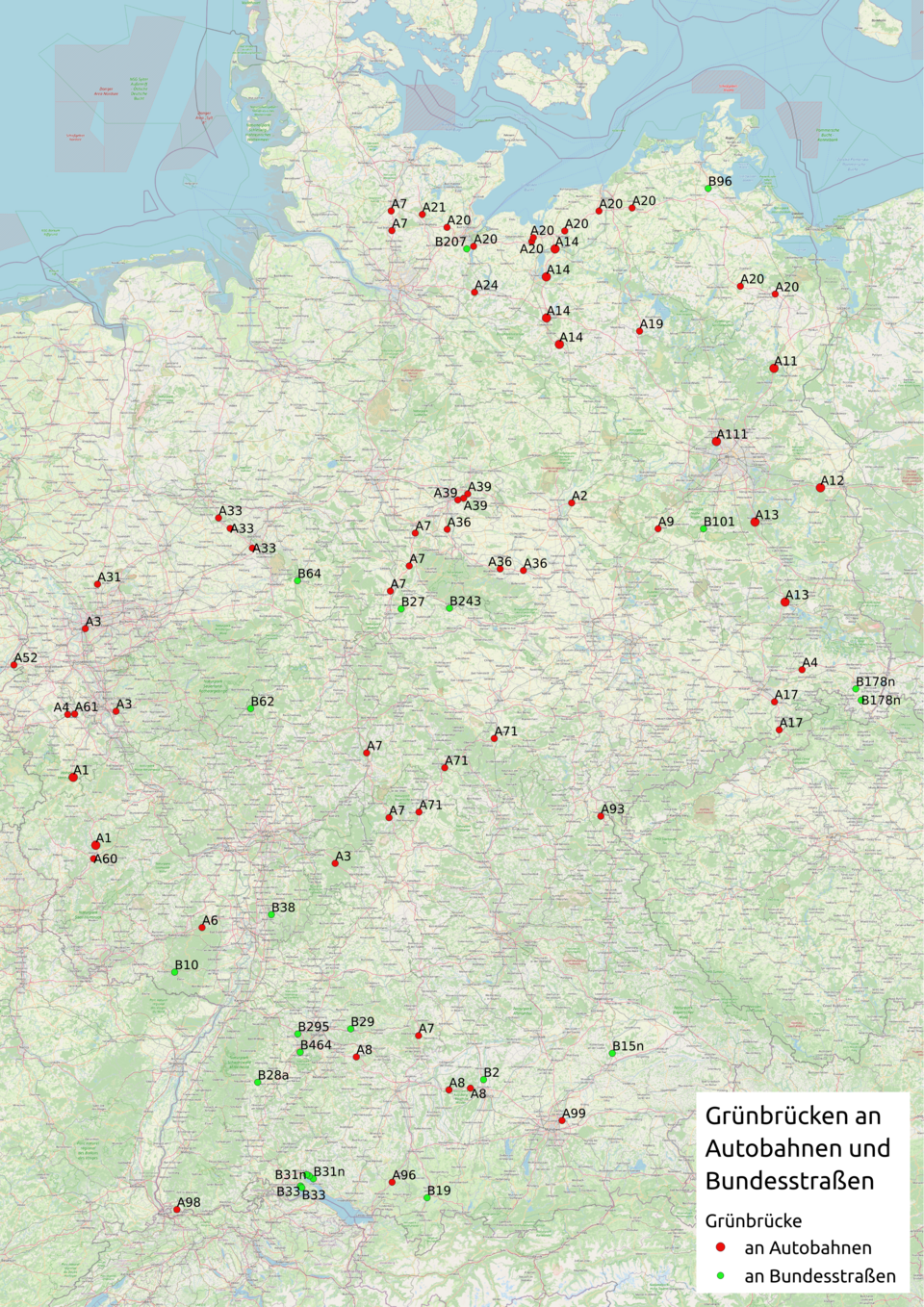

Connectivity can be enhanced via wildlife corridors, eco-ducts or overpasses that link isolated patches across transport networks.

Map of Germany’s designated green bridges (ecoducts) across motorways and federal roads, illustrating where structural wildlife corridors restore landscape connectivity. Such overpasses reduce barrier effects and help maintain movement and gene flow among fragmented populations. Source.

Corridors reduce road mortality and maintain gene flow when paired with fencing and appropriately designed crossing structures.

Vegetated wildlife overpass spanning the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park, designed to reconnect habitat separated by a major roadway. Overpasses like this are paired with fencing to guide animals, reducing collisions and restoring functional connectivity. Source.

UNESCO Biosphere Reserves

UNESCO biosphere reserves represent an internationally recognised model of sustainable conservation. They balance biodiversity protection with human development through zoning.

UNESCO biosphere reserves use a core, buffer, and transition zone model to integrate in situ conservation with sustainable use.

Zoning System

Core Zone: Strictly protected, minimal human interference, conserving key species and habitats.

Buffer Zone: Surrounds the core; limited human activity such as research, education, and eco-friendly tourism allowed.

Transition Zone: Outermost area where sustainable resource use and community development occur.

This zoning ensures biodiversity conservation while engaging local communities.

Sustainable Management

UNESCO reserves stress sustainable management by integrating conservation with socio-economic development:

Involving local communities in decision-making.

Promoting education and research.

Encouraging sustainable farming, fishing, and ecotourism in transition zones.

Sustainable Management: Use of resources in ways that meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.

Factors Influencing Reserve Effectiveness

The success of reserve design depends on ecological, social, and political conditions.

Ecological Considerations

Reserve placement in biodiversity hotspots maximises conservation value.

Presence of keystone or umbrella species can guide design.

Climate change resilience requires corridors and altitudinal diversity.

Social and Political Considerations

Local community support prevents conflict and ensures compliance.

National legislation and funding provide stability.

International frameworks like the Convention on Biological Diversity reinforce commitment.

Practical Challenges

Despite best intentions, reserve design faces challenges:

Fragmentation due to urbanisation or agriculture reduces effectiveness.

Insufficient size for wide-ranging species like elephants or wolves.

Conflict with development goals can erode protected areas.

Poaching and illegal trade persist even within designated reserves.

Key Takeaways

Reserve design requires integrating ecological principles with human needs.

Edges and corridors must be managed carefully to balance biodiversity conservation with ecosystem connectivity.

UNESCO biosphere reserves illustrate how conservation and sustainable use can coexist through zoning systems.

FAQ

Circular reserves minimise the proportion of habitat exposed to edges, reducing the impact of invasive species, predators, and microclimatic shifts.

Irregular or elongated shapes increase the edge-to-core ratio, meaning more of the reserve is subject to edge effects. This often results in less protection for interior specialist species.

While corridors facilitate migration and genetic exchange, they can also create risks.

They may act as conduits for disease or invasive species.

Animals using corridors can become more vulnerable to hunting or road accidents.

Poorly designed corridors may fail to meet species’ behavioural or ecological needs.

Planners often use umbrella species—large, wide-ranging species whose protection indirectly safeguards many others.

Alternatively, keystone species may be chosen because their ecological role supports entire communities. Social, cultural, or economic values can also influence species selection.

The scale of reserves must match species’ ecological needs.

Local reserves may protect small mammals or plants with limited ranges.

Regional or transboundary reserves are essential for migratory birds, elephants, or carnivores.

Connectivity at larger scales reduces vulnerability to climate change and habitat fragmentation.

Infrastructure like roads, farms, or settlements intensifies edge pressures by fragmenting habitat and increasing disturbance.

Noise, pollution, and light from human activity can penetrate into the reserve, altering animal behaviour. Buffer zones are crucial in mitigating these pressures by separating high-impact areas from core habitats.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Define the term edge effects and explain briefly why they are significant in reserve design.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for defining edge effects as changes in population or community structures at the boundary of two habitats.

1 mark for explaining their significance in reserve design, e.g. that they can increase predation, invasive species intrusion, or alter microclimatic conditions.

Question 2 (5 marks):

Discuss how the design of a biosphere reserve, including its zoning system (core, buffer, transition), helps balance biodiversity conservation with sustainable human use.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying the core zone as strictly protected for conservation of species and habitats.

1 mark for describing the buffer zone where limited, low-impact activities such as research or ecotourism are permitted.

1 mark for describing the transition zone where sustainable development and human activities take place.

1 mark for linking the zoning system to reducing human impacts while still allowing socio-economic use.

1 mark for explaining how this integrated approach supports both conservation goals and community involvement/benefits.