IB Syllabus focus:

‘Mitigate via permits, quotas, seasons, mesh sizes, zoning, labels and behaviour change. MPAs protect spawning/nursery areas and boost nearby fisheries through spillover.’

Policies, marine protected areas (MPAs), and consumer actions are central to sustainable aquatic resource management, helping regulate exploitation, protect biodiversity, and encourage responsible consumption of marine products.

Policy Measures for Sustainable Fisheries

Fishing Permits and Licences

Governments and regional fisheries organisations often require fishers to obtain permits or licences, which regulate who may fish, what methods they can use, and in which areas. These permits form the legal foundation of fisheries management and ensure that only authorised individuals or organisations can exploit fish stocks.

Quotas and Catch Limits

Quotas set maximum allowable catches for particular fish species to prevent overexploitation. By linking quotas to scientific stock assessments, policymakers aim to align harvest levels with the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Quotas are typically allocated nationally or regionally and can be further divided among fleets or individual fishers.

Seasonal Restrictions

Fishing seasons restrict activity to specific times of year when stocks are most resilient. For instance, closed seasons often coincide with spawning periods to allow populations to reproduce. These restrictions reduce ecological stress and increase long-term productivity of fisheries.

Gear Regulation and Mesh Sizes

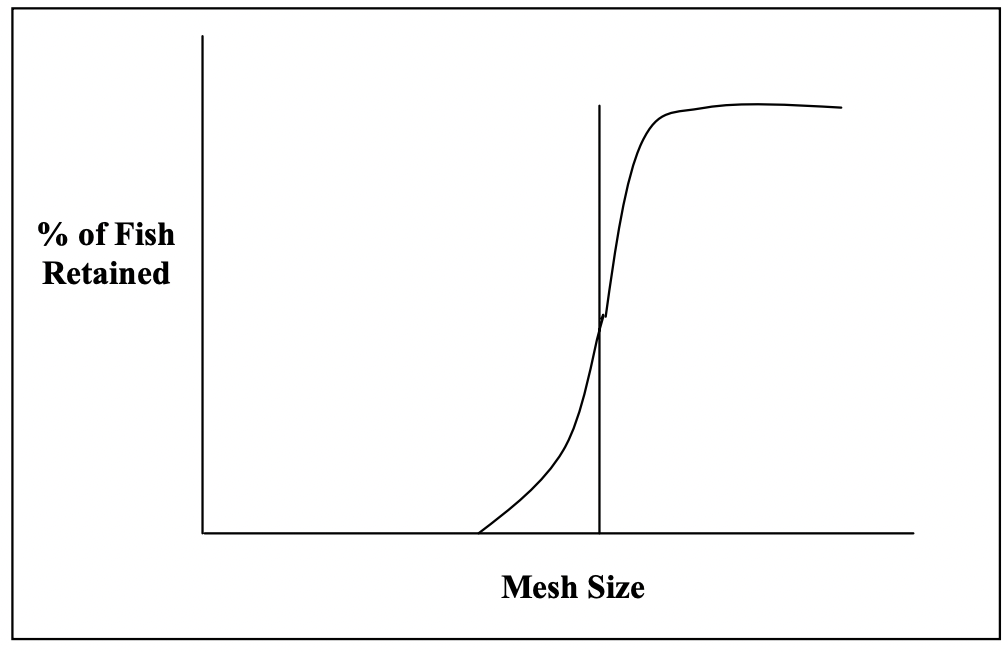

Mesh size restrictions prevent the capture of undersized or juvenile fish.

The S-shaped selectivity curve shows how cod-end mesh gradually retains a larger proportion of fish as body size increases, illustrating why larger mesh sizes let juveniles escape. This directly supports the use of mesh-size controls to reduce bycatch and protect recruitment. Source.

By allowing smaller fish to escape, regulations enhance stock renewal and reduce wasteful bycatch. Other gear controls may prohibit destructive practices such as bottom trawling in sensitive habitats.

Spatial Zoning

Zoning involves designating certain waters for specific purposes, such as fishing, conservation, or recreation. This spatial separation reduces conflicts among users and ensures critical habitats are preserved.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

Purpose and Function

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are zones where human activities are managed or restricted to safeguard ecosystems and biodiversity. MPAs are particularly important for protecting spawning and nursery grounds, which are essential for replenishing fish stocks.

Marine Protected Area (MPA): A designated marine zone where activities such as fishing, drilling, or tourism are controlled or prohibited to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem functions.

MPAs can range from no-take zones, where extraction is banned, to multi-use areas with varying levels of restrictions. By limiting exploitation, MPAs allow ecosystems to recover from overfishing and habitat degradation.

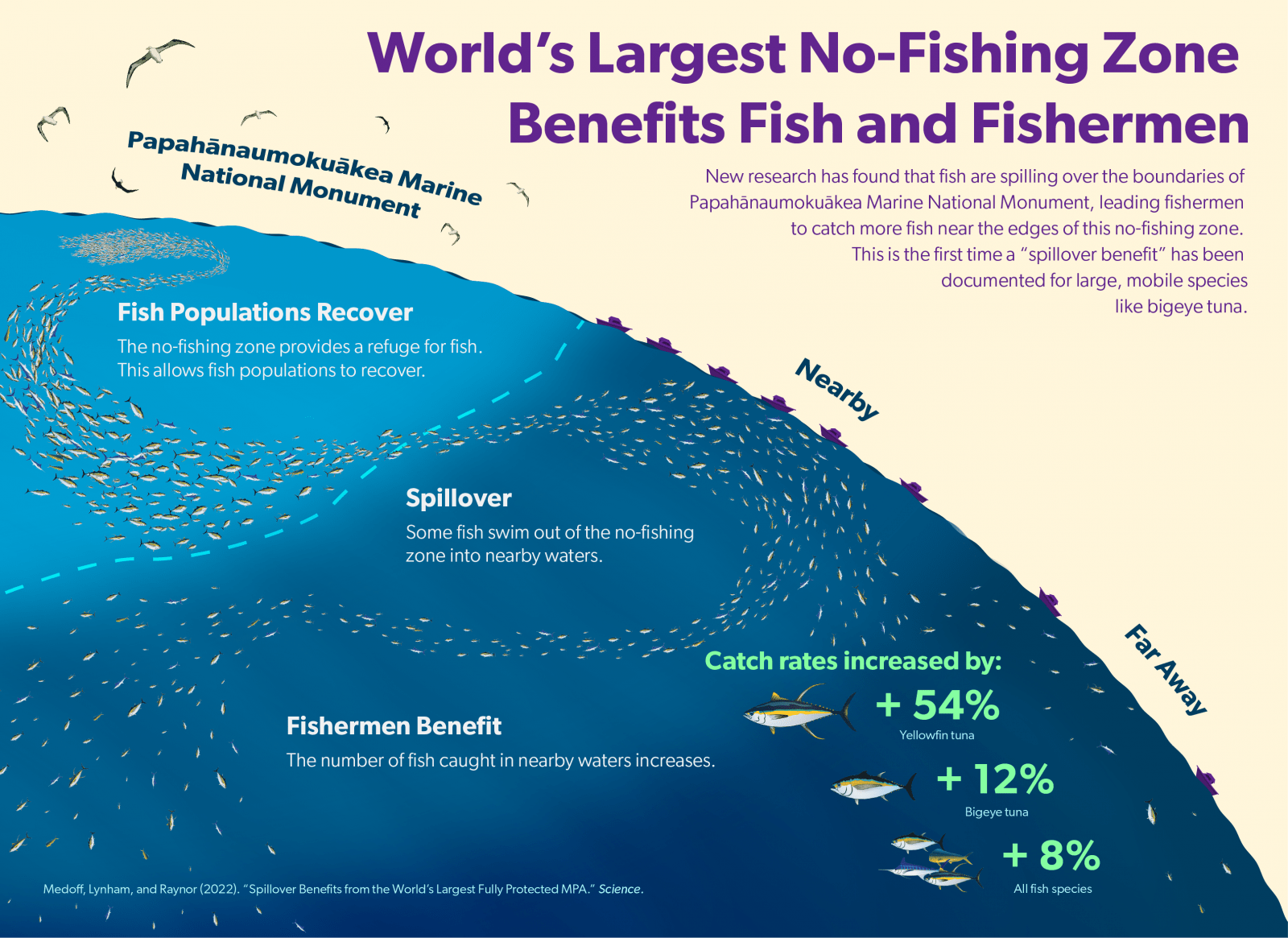

Spillover Effect

One of the key benefits of MPAs is the spillover effect, where fish populations inside protected areas grow and expand beyond boundaries, boosting catches in adjacent fisheries.

This diagram depicts fish biomass building inside a no-fishing zone and spilling over across the boundary into nearby fishing grounds, increasing catch rates close to the MPA. The percentages shown are study-specific results for tuna near the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and are included for context beyond the syllabus concept. Source.

This provides both ecological and economic benefits.

Global Examples

Well-managed MPAs, such as the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia, demonstrate how effective regulation can preserve biodiversity while supporting sustainable tourism and fishing.

Consumer Actions

Eco-Labels and Certification Schemes

Labels such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certify seafood products harvested through sustainable practices.

The MSC Blue Label is a consumer-facing certification mark for sustainably caught wild seafood, used at point of sale and on packaging to influence purchasing decisions. This logo is shown here only as an identifier of the label referenced in the syllabus and notes. Source.

Eco-Label: A certification mark on products indicating they meet specific environmental or sustainability criteria.

Shifts in Consumption Behaviour

Consumer demand directly influences fisheries. Increased awareness encourages people to choose sustainably sourced fish, reduce waste, and diversify diets to ease pressure on popular species such as tuna or cod. Behavioural shifts, including eating lower on the food chain (e.g., mussels, sardines), can significantly reduce ecological impacts.

Public Campaigns and Awareness

NGOs and governments promote awareness campaigns to encourage responsible seafood consumption. Citizen participation in campaigns, petitions, and social media movements strengthens accountability and drives market demand for sustainable options.

Integrated Approaches

Linking Policy, MPAs, and Consumers

Sustainable aquatic management is most effective when policy frameworks, protected areas, and consumer behaviour interact synergistically.

Policy provides enforceable regulations.

MPAs safeguard ecological processes.

Consumer choices drive market transformation.

This integration ensures that overexploited ecosystems can recover, while human societies continue to benefit from aquatic resources.

Challenges

Despite these measures, challenges persist, including:

Limited enforcement capacity in many countries.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Resistance from stakeholders dependent on unrestricted fishing.

Difficulty in changing entrenched consumer habits.

FAQ

Citizens can collect data on fish abundance, illegal fishing, or habitat quality using mobile apps or community surveys.

This information can:

Supplement government monitoring.

Raise local awareness of conservation needs.

Increase accountability for policymakers and industry.

Involving citizens also builds local ownership of MPA success, making regulations more socially acceptable.

Enforcement often requires costly patrols, surveillance, and monitoring technology, which many governments struggle to fund.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing can occur within or near MPAs, undermining protection.

Community resistance may also arise if restrictions are introduced without local consultation, especially where livelihoods depend on fishing access.

Eco-labels undergo third-party certification processes that assess fisheries against sustainability criteria such as stock health, ecosystem impacts, and management effectiveness.

Regular audits, chain-of-custody tracking, and transparency in reporting strengthen trust. However, criticism exists when smaller fisheries cannot afford certification, potentially creating barriers for developing countries.

Price sensitivity often leads consumers to choose cheaper, non-certified seafood.

Cultural preferences for certain species, such as cod or tuna, limit dietary change.

Awareness campaigns may not reach all demographics equally, reducing their impact on purchasing patterns.

Agreements such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provide frameworks for nations to cooperate on high-seas fishing.

Regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs) coordinate quotas, gear restrictions, and enforcement across national boundaries.

Such agreements reduce conflict and ensure consistency when fish stocks migrate across jurisdictions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State two policy measures, other than the creation of marine protected areas, that can help reduce overexploitation of fisheries.

Mark scheme:

Award 1 mark for each correct policy measure up to a maximum of 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include:

Quotas or catch limits (1 mark)

Seasonal restrictions (1 mark)

Gear regulation, e.g., mesh size limits (1 mark)

Fishing permits or licensing (1 mark)

Spatial zoning of fishing areas (1 mark)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how marine protected areas (MPAs) and consumer actions can work together to improve the sustainability of fisheries.

Mark scheme:

Clear description of MPAs protecting spawning/nursery grounds and supporting biodiversity (1 mark).

Explanation of the spillover effect and how it benefits adjacent fisheries (1 mark).

Reference to eco-labels (e.g., MSC) guiding consumers towards sustainable seafood (1 mark).

Explanation of how consumer demand influences fishing practices and market behaviour (1 mark).

Linking the roles of both MPAs and consumer actions to create an integrated system that strengthens long-term sustainability of fisheries (1 mark).

Maximum: 5 marks.