IB Syllabus focus:

‘Farms vary by outputs, purpose and inputs (arable, pastoral, subsistence/commercial, intensive/extensive, irrigated/rain-fed, organic/inorganic). Traditional nomadism and slash-and-burn suited low densities but are less sustainable under modernization and higher populations.’

Agricultural systems are diverse and reflect different environments, technologies, and cultural practices. Traditional approaches remain significant but face growing challenges under modern pressures and rising populations.

Types of Agricultural Systems

Arable and Pastoral Systems

Arable farming focuses on cultivating crops, typically in fertile soils with suitable climates.

Pastoral farming involves rearing livestock such as cattle, sheep, or goats, often in areas unsuitable for crops.

Arable Farming: Cultivation of crops for food, fibre, or industrial products.

These systems may overlap in mixed farming, where crops and animals are integrated to optimise land use and nutrient cycling.

Subsistence and Commercial Systems

Subsistence farming produces food mainly for local consumption by farmers and their families.

Commercial farming is profit-oriented, producing crops or livestock for regional, national, or global markets.

Subsistence systems often rely on labour-intensive methods, while commercial systems typically employ mechanisation, advanced inputs, and large-scale management.

Intensive and Extensive Systems

Intensive systems maximise productivity per unit area, often using high levels of labour, fertilisers, and technology.

Extensive systems spread over larger areas with lower input per unit land, such as cattle ranching in dry grasslands.

Intensive Agriculture: Farming system characterised by high input and output per unit area.

Intensive systems often produce greater yields but may cause environmental stress, while extensive systems require more land and are vulnerable to degradation.

Irrigated and Rain-fed Systems

Irrigated agriculture relies on artificial watering systems, crucial in arid and semi-arid regions.

Rain-fed agriculture depends entirely on natural precipitation.

Reliance on irrigation can increase food security but often leads to salinisation and overuse of freshwater.

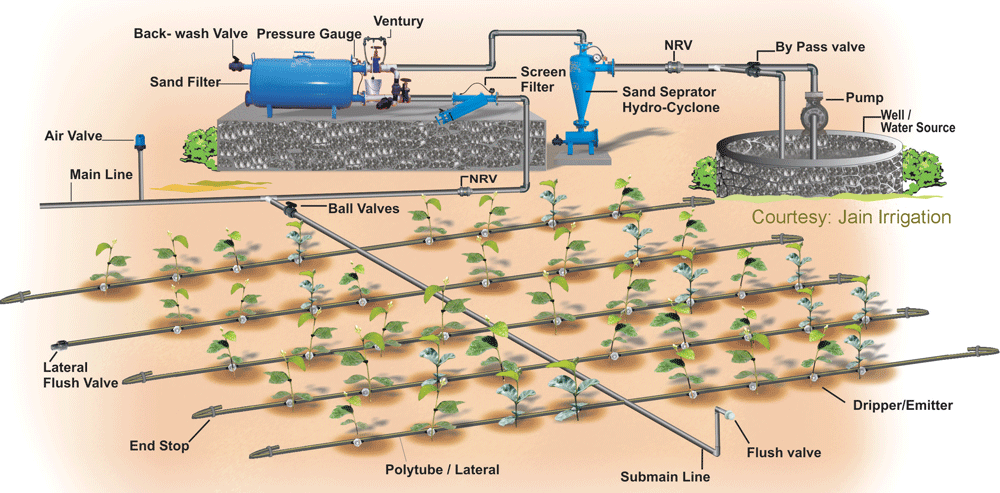

A labelled diagram of a drip-irrigation layout showing mainline, filters, valves, laterals, and emitters that deliver water directly to plant roots. This exemplifies irrigated agriculture discussed in the notes, contrasting with rain-fed systems. Component-level labels provide extra technical detail beyond the syllabus scope. Source.

Organic and Inorganic Systems

Organic systems prohibit synthetic chemicals, relying on composts, manures, and biological pest control.

Inorganic systems employ synthetic fertilisers, herbicides, and pesticides to maximise yields.

Organic farming prioritises soil health and biodiversity, while inorganic approaches can raise productivity but at environmental costs.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Nomadism

Nomadic pastoralism involves herders moving livestock seasonally to find fresh grazing land.

Transhumant herder with a flock on summer pasture, illustrating seasonal livestock movement to match forage availability—closely related to nomadic pastoralism in the notes. This visual reinforces how pastoral systems depend on mobility across landscapes. The UNESCO heritage framing is extra contextual detail not required by the syllabus. Source.

Nomadic Pastoralism: A traditional system where communities move with livestock in search of pasture and water.

Historically sustainable under low population densities, it now faces strain from land privatisation, political borders, and reduced grazing areas.

Slash-and-Burn Agriculture

Also known as swidden cultivation, this practice clears small patches of forest by cutting and burning vegetation. Ash adds nutrients to the soil, allowing short-term cultivation.

A recently burned field with felled trunks in Chiang Mai, Thailand, typical of small-plot swidden cultivation where ash temporarily enriches soils. The image makes visible the clearing-and-burning stage referenced in the notes. Geographic context beyond the syllabus is included. Source.

Effective in nutrient-poor tropical soils.

Requires long fallow periods for soil recovery.

Sustainable with small populations and ample forest land.

Slash-and-Burn Agriculture: Traditional method of clearing forest for temporary cultivation by cutting and burning vegetation.

With rising populations, shorter fallow times degrade soils, reduce biodiversity, and increase greenhouse gas emissions.

Modernisation and Sustainability Challenges

Population Pressure

Higher populations shorten fallow periods in slash-and-burn systems, leading to soil exhaustion.

Nomadic practices become unsustainable as grazing land diminishes.

Demand for food pushes traditional systems towards commercialisation.

Environmental Concerns

Deforestation from slash-and-burn contributes to climate change.

Overgrazing in nomadic systems can cause desertification.

Intensive commercial systems lead to fertiliser runoff, pesticide pollution, and reduced biodiversity.

Transition to Modern Systems

Traditional systems are increasingly replaced or adapted:

Agroforestry combines trees with crops for soil fertility and shade.

Crop rotation maintains soil nutrients.

Sustainable grazing management prevents overuse of pasture.

These hybrid approaches seek to balance traditional knowledge with scientific innovation.

Key Features of Agricultural System Variability

Agricultural systems are shaped by:

Inputs: labour, fertilisers, technology, land area, water.

Outputs: crop yields, livestock products, income.

Purpose: subsistence versus commercial orientation.

Bullet-point overview:

Arable: crops.

Pastoral: livestock.

Subsistence: local consumption.

Commercial: profit-driven.

Intensive: high input/output per unit area.

Extensive: low input/output, large areas.

Irrigated: artificial water supply.

Rain-fed: reliant on precipitation.

Organic: natural inputs, biodiversity-friendly.

Inorganic: synthetic inputs, high productivity.

Cultural and Social Context

Traditional systems are deeply tied to cultural identities. Nomadism fosters community resilience, while slash-and-burn represents adaptation to tropical ecosystems. Yet modern pressures often marginalise these practices.

Shifts in diet, urbanisation, and global markets increasingly determine agricultural choices, challenging traditional methods but also creating opportunities for sustainable adaptation.

FAQ

Intensive systems are defined by high labour, fertiliser, and technology inputs relative to land size, producing high yields on smaller plots.

Extensive systems spread over larger areas with low input per unit area. Productivity depends more on land availability than inputs.

Irrigation can maintain crop growth in arid climates, but excessive use often leads to waterlogging and salinisation.

Minerals accumulate in the soil as water evaporates, reducing fertility and harming plant growth. Sustainable irrigation relies on careful water management.

Organic farming builds soil structure, biodiversity, and nutrient cycling without synthetic inputs, offering long-term resilience.

Inorganic systems may provide faster yields but risk soil degradation, nutrient imbalances, and dependency on fossil-fuel-based fertilisers.

Restricted access to grazing lands due to privatisation and political borders.

Conflicts with sedentary farmers over resources.

Climate variability reducing available pasture.

These challenges make mobility harder, threatening the sustainability of nomadic traditions.

Tropical soils are often nutrient-poor due to heavy rainfall leaching minerals.

Burning vegetation releases ash rich in nutrients, creating short-term fertile plots. However, without long fallow periods, soils degrade quickly, making the practice less sustainable today.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify and briefly describe two types of agricultural systems based on inputs or purpose.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for correctly identifying each system (max 2).

Acceptable answers include: arable, pastoral, subsistence, commercial, intensive, extensive, irrigated, rain-fed, organic, inorganic.

Award mark only if a short description is provided alongside the name (e.g., "Arable farming: cultivation of crops" earns the mark).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain why traditional practices such as nomadic pastoralism and slash-and-burn agriculture were historically sustainable, and discuss why they have become less sustainable in modern contexts.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for explaining historical sustainability:

Nomadism sustainable under low population densities and large grazing areas (1 mark).

Slash-and-burn sustainable when fallow periods allowed soil recovery (1 mark).

Up to 3 marks for reasons why less sustainable today:

Population growth reducing available land (1 mark).

Shortened fallow periods leading to soil exhaustion (1 mark).

Political boundaries or privatisation restricting mobility of nomadic groups (1 mark).

Increased deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions from slash-and-burn (alternative valid point, 1 mark).

Maximum 5 marks in total.