OCR Specification focus:

‘Reasons for and aims of the Third Crusade; the development of the idea of Jihad; Zengi, Nur ad Din and Saladin.’

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) arose from the catastrophic loss of Jerusalem in 1187. European leaders sought to restore Christian control, while the Islamic concept of jihad matured under successive leaders.

Background to the Third Crusade

The immediate trigger was the Battle of Hattin (1187), where Saladin’s forces destroyed the crusader army and captured the relic of the True Cross. This led to the surrender of Jerusalem, the most sacred site for Western Christendom, which shocked Europe and transformed the papacy’s priorities. The crusading ideal had already suffered from the failure of the Second Crusade, but this new crisis provided fresh urgency.

Religious Shock in the West

For Christians, the loss of Jerusalem was not simply territorial but spiritual. The city was regarded as the centre of Christendom, and its occupation by Muslim forces was viewed as a divine punishment for sin and disunity among Christians. The Pope responded with calls for repentance and renewed holy war.

Reasons for the Third Crusade

Several interlinked motivations explain why the Third Crusade was launched.

Religious motives

The desire to recover Jerusalem and other holy sites for Christendom.

Belief in crusading as an act of penance, promising remission of sins.

Restoring Christian prestige after the humiliations of 1187.

Political motives

The crusade offered kings such as Richard I of England and Philip II of France an opportunity to display leadership and consolidate their authority.

Rivalry among rulers made participation both a necessity and a chance for personal glory.

The Papacy aimed to assert its moral authority by uniting Christendom against a common enemy.

Practical motives

Protecting remaining crusader strongholds, such as Tyre, which still resisted Saladin.

Safeguarding pilgrimage routes and Christian settlers in the Levant.

Re-establishing trade connections with the eastern Mediterranean.

Jihad: In Islamic tradition, jihad means “struggle” or “striving.” In the crusading context, it referred to the religious duty to defend or expand Muslim lands against non-believers.

Aims of the Crusaders

Although united by the desire to reclaim the Holy Land, crusading leaders did not share identical aims.

Papal Aims

The papacy sought:

The recovery of Jerusalem.

The strengthening of papal leadership across Christendom.

Reform of Christian society through penitential warfare.

Royal Aims

Richard I aimed at military victory and securing his reputation as a Christian warrior king.

Philip II was motivated by piety, but also by rivalry with Richard, seeking to ensure France was not overshadowed.

Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire hoped to unite his realm through a victorious campaign, though his sudden death in 1190 ended his expedition prematurely.

Wider Aims

Defence and reinforcement of the crusader states still surviving in the Levant.

Ensuring long-term Western presence and influence in the Near East.

Demonstrating divine favour through the recovery of holy sites.

The Development of the Idea of Jihad

The Third Crusade cannot be understood without examining the parallel development of jihad in the Islamic world.

Zengi (d. 1146)

Atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo.

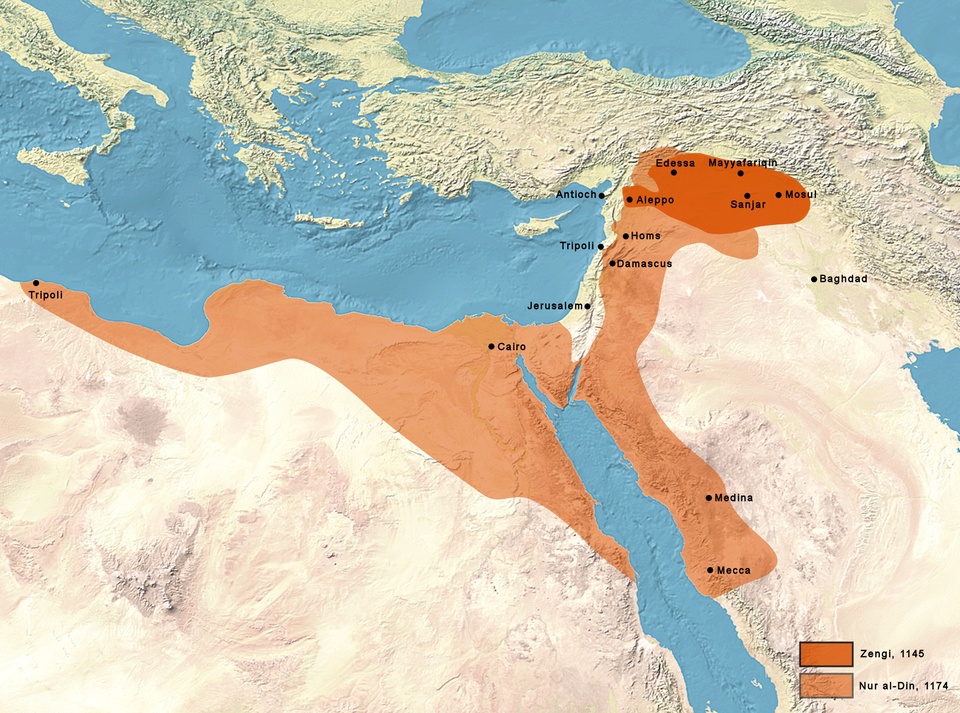

A labelled map showing the Zengid dynasty’s territories across northern Mesopotamia and Syria. This illustrates the geopolitical platform from which Zengi and Nūr al-Dīn advanced a unifying jihad ideology. Source

He first framed warfare against the crusaders as religious jihad, presenting himself as defender of Islam.

His capture of Edessa in 1144 was hailed as a triumph of jihad and galvanised the Muslim world.

Nur ad Din (1118–1174)

Zengi’s son and successor.

Deeply pious and committed to jihad as a religious duty.

Promoted unity across the Muslim world, building mosques and madrasas to spread the ideology of holy struggle.

Sought to overcome divisions between Muslim rulers, stressing the need for solidarity against the Franks.

Saladin (1137–1193)

Rose to power in Egypt before uniting Egypt and Syria under his rule.

Developed jihad into both a spiritual and political cause, blending religious devotion with practical strategy.

His leadership transformed jihad into a mass movement, with sermons and poetry celebrating the defence of Islam.

His decisive victory at Hattin (1187) was presented as the culmination of jihad, justifying the recapture of Jerusalem.

Saladin’s chivalry and diplomacy also shaped Western perceptions, though his image was more complex in the Islamic world.

Holy War: Warfare conducted for religious reasons and sanctioned by divine authority. In Christian Europe, it was linked to papal approval and the promise of spiritual reward.

Interaction Between Crusader Aims and Jihad

The Third Crusade emerged from the clash of two powerful religious ideas:

On the one hand, Christian crusading, emphasising penitential warfare to reclaim sacred space.

On the other, Muslim jihad, urging defence and expansion of Islam under unified leadership.

This created a conflict framed not only as a struggle for land but as a battle of faiths. The ideological commitment of both sides explains the ferocity of the war and its enduring legacy.

Legacy of the Aims

The reasons and aims of the Third Crusade illustrate the convergence of:

Religion (the recovery of Jerusalem and salvation of souls).

Politics (kingship, rivalry, and papal authority).

Ideology (jihad and crusading as parallel holy wars).

Together, they defined the crusade as both a military expedition and a spiritual confrontation, ensuring its lasting place in medieval history.

FAQ

The fall of Edessa was the first major crusader state to collapse, proving that Christian territories were not invincible.

Zengi presented the victory as a triumph of jihad, framing resistance to the crusaders in explicitly religious terms. This shaped Muslim political culture, showing that faith could unify diverse Muslim populations against external threats.

Nur ad Din’s emphasis on jihad extended into daily religious life.

He commissioned madrasas and mosques to spread Islamic learning.

Religious scholars and preachers were encouraged to emphasise unity against the crusaders.

His patronage embedded jihad as both a spiritual obligation and a political necessity.

This helped make jihad part of the broader social fabric, not just a call to arms.

Saladin combined personal piety with political pragmatism.

He emphasised mercy and restraint, which won admiration from both Muslim followers and some Christian observers. His unification of Egypt and Syria gave jihad practical weight, transforming it from scattered rhetoric into coordinated action.

Saladin’s charisma and reputation for justice made jihad a rallying cause across the Muslim world.

The shock went beyond military defeat.

Jerusalem was seen as the ultimate symbol of Christian devotion.

Its loss prompted widespread penitential movements, with sermons and processions across Europe.

Many believed the disaster was punishment for corruption within Christendom, increasing pressure for reform.

This framed the Third Crusade as both spiritual redemption and political recovery.

The Pope used the loss of Jerusalem to reinforce papal supremacy.

By calling for a new crusade, the papacy positioned itself as the moral leader of Christendom. The indulgences offered for participation underlined papal control over salvation.

The crusade also allowed the Pope to influence powerful monarchs, binding their military ambitions to papal-approved aims of recovering holy sites.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Which Muslim leader first presented warfare against the crusaders as a form of jihad?

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying Zengi.

1 additional mark for specifying his role as Atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo or linking him to the capture of Edessa (1144).

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain two reasons why the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 led to the launch of the Third Crusade.

Mark Scheme:

Up to 3 marks for the first reason:

1 mark for basic identification (e.g. “Religious shock at the loss of the Holy City”).

1 mark for explanation (e.g. “Jerusalem was central to Christian faith as the site of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection”).

1 mark for development (e.g. “Its loss was interpreted as divine punishment for Christian disunity, increasing papal urgency”).

Up to 3 marks for the second reason:

1 mark for basic identification (e.g. “Political motivation for kings to assert leadership”).

1 mark for explanation (e.g. “Rulers such as Richard I saw recovery of Jerusalem as an opportunity to enhance prestige”).

1 mark for development (e.g. “Participation offered both personal glory and the chance to consolidate royal authority while uniting Europe under papal leadership”).