OCR Specification focus:

‘Problems in Outremer, Hattin (1187) and the loss of Jerusalem (1187); reasons for the failure of Frederick Barbarossa’s expedition’

The crisis of Outremer and the failure of Frederick Barbarossa’s campaign reveal how fragile Christian control had become by 1187. Both internal weaknesses and external pressures shaped these events.

Problems in Outremer before 1187

The Crusader States, collectively referred to as Outremer, were always vulnerable due to geography and demography. By the late twelfth century, these vulnerabilities were becoming increasingly acute.

Political weaknesses

The Kingdom of Jerusalem had endured disputes over succession following the death of King Amalric (1174).

Rule passed to Baldwin IV, who suffered from leprosy, raising questions over stability.

A bitter dispute arose between the court faction led by Baldwin IV’s sister Sibylla and her husband Guy of Lusignan, and the noble faction led by Raymond of Tripoli.

These rivalries produced disunity at a time when united leadership was desperately needed.

Outremer: The collective term for the Crusader States established in the Levant after the First Crusade, including Jerusalem, Antioch, Edessa, and Tripoli.

The disunity meant that defensive strategy was inconsistent. Factions sometimes refused cooperation, weakening collective resistance against Muslim advances.

Military and demographic limitations

Outremer had a small Frankish population, heavily reliant on reinforcements and settlers from Europe.

Most knights were tied to local defence, limiting the ability to mount large field armies.

The Military Orders (Templars and Hospitallers) provided professional warriors, but their independent command structures sometimes clashed with royal policy.

Castles such as Kerak and Crac des Chevaliers provided defensive strongholds, but these were expensive to maintain and often isolated.

Strategic pressures

Muslim power had become increasingly centralised under Saladin, who by 1174 controlled both Egypt and Syria.

Saladin promoted Jihad, strengthening Islamic unity against the Crusader States.

Outremer was caught between stronger, more united Muslim forces, while simultaneously undermined by its own political divisions.

The Battle of Hattin (1187)

The culmination of these problems was the catastrophic defeat at Hattin.

Events leading to Hattin

Guy of Lusignan, pressured to show leadership, raised a field army to confront Saladin.

Against advice, he marched across arid territory towards Tiberias in July 1187.

Saladin’s forces harassed the Crusaders, cutting them off from water supplies and wearing them down.

The battle itself

The Crusader army was exhausted and encircled near the Horns of Hattin.

Saladin used fire and smoke to worsen thirst and disarray.

The Frankish infantry collapsed, while the knights, unable to charge effectively, were overwhelmed.

The True Cross, the most sacred relic of the Crusaders, was captured.

King Guy himself was taken prisoner, though later released.

Consequences

Hattin destroyed most of the Frankish field army.

Castles and cities fell rapidly as there were no forces left to relieve them.

By October 1187, Jerusalem surrendered to Saladin after a short siege.

Synoptic map of the Latin East (1190) showing the Kingdom of Jerusalem reduced largely to coastal holdings alongside Antioch and Tripoli within a wider Ayyubid sphere. This gives clear spatial context for Outremer’s vulnerability after 1187. The map includes broader regional framing for orientation. Source

The Failure of Frederick Barbarossa’s Expedition

The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa led one of the largest contingents of the Third Crusade. His expedition began with great promise but ended in disaster.

Strengths of the expedition

Frederick raised a huge army, estimated at 15,000–20,000 men, including many seasoned knights.

He planned an overland march through Hungary, Byzantium, and Anatolia, retracing the route of the First Crusade.

His prestige as Emperor gave him authority unmatched by other crusader leaders.

Challenges faced

Relations with the Byzantine Empire were tense. The Emperor Isaac II Angelos feared Frederick’s army might seize territory, slowing negotiations and movement.

Once in Anatolia, Frederick’s army faced supply difficulties, heat, and constant skirmishes with Turkish forces.

Maintaining discipline and morale across such a long march was extremely difficult.

The turning point

In June 1190, as the army crossed the River Saleph in Cilicia, Frederick drowned—possibly swept away while bathing or attempting to cross on horseback. His death was devastating:

Many German soldiers deserted and returned home.

Leadership passed to his son Frederick of Swabia, but the force was much diminished.

Only a small contingent eventually reached Antioch and Acre, limiting German impact on the Third Crusade.

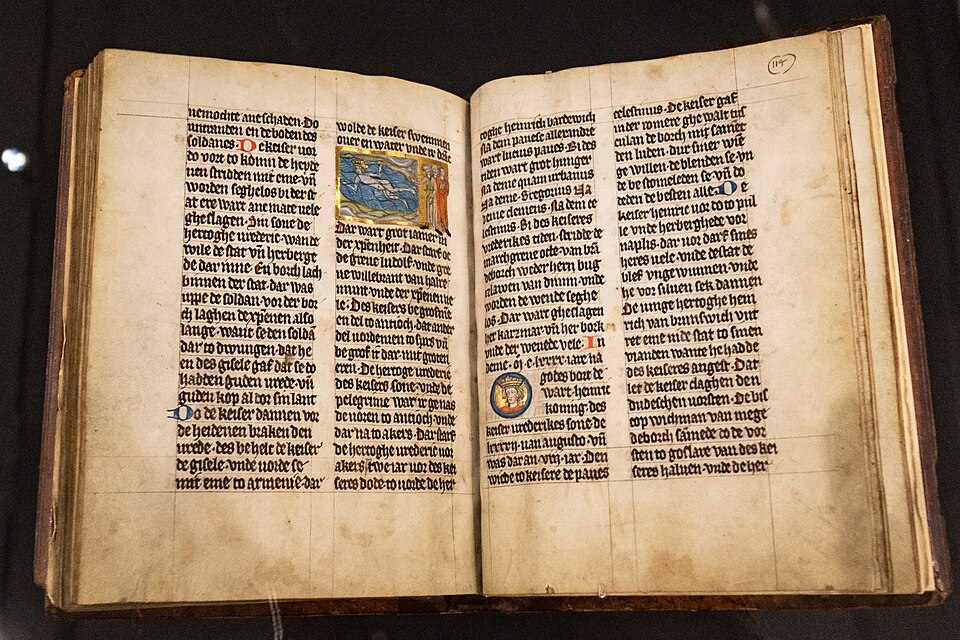

Miniature from the Sächsische Weltchronik depicting Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa) drowning in the River Saleph during the Third Crusade. The scene underscores the collapse of command and morale that followed. Source

Frederick I Barbarossa: Holy Roman Emperor (1155–1190) who led the German contingent of the Third Crusade. His accidental death in 1190 caused the collapse of his expedition.

Reasons for failure

Geographical challenges of the overland route through hostile territory.

Suspicious diplomacy with Byzantium, which delayed progress.

Loss of leadership with Barbarossa’s sudden death, destroying morale and cohesion.

The desertion of troops, reducing the crusading force to a shadow of its former size.

The Wider Impact

The fall of Jerusalem and the collapse of Barbarossa’s expedition illustrate the fragility of Christian rule in the East:

Outremer was weakened by internal divisions, small manpower, and overextension.

Saladin’s unified command and religious legitimacy gave the Muslims strategic advantage.

Western hopes for recovery were dashed when one of the most powerful leaders of Europe failed to bring his army intact to the Holy Land.

FAQ

Saladin deliberately drew the Crusaders into unfavourable terrain, away from secure water sources. By threatening Tiberias, he provoked Guy of Lusignan to march his army into arid conditions.

This strategy exploited the Crusaders’ need to defend their lands while ensuring they were exhausted and vulnerable before battle. The Horns of Hattin provided a natural position for encirclement.

The True Cross was believed to be the holiest relic in Christendom, carried into battle for divine favour.

Its capture was a huge psychological blow for the Crusaders, undermining morale and religious legitimacy.

For Muslims, displaying the relic after the battle demonstrated divine support for their cause, strengthening Saladin’s reputation as leader of jihad.

Barbarossa’s German host was one of the largest single armies ever sent to the East, with perhaps 15,000–20,000 soldiers.

It included a significant proportion of knights and well-equipped infantry.

The force was organised through imperial command, giving it greater cohesion than most crusader contingents.

However, its size created logistical challenges, particularly in feeding and supplying troops during the march through Anatolia.

Many nobles saw little point in continuing without the Emperor’s leadership.

Some abandoned the campaign entirely, returning home with their men.

Others quarrelled over succession, weakening unity.

Frederick of Swabia assumed command, but his authority was limited compared to his father’s, and he struggled to inspire the same loyalty.

The fragmentation of the army meant only a small fraction reached Acre.

The loss of Jerusalem shocked Christian Europe, producing urgent calls for a new crusade.

Pope Gregory VIII issued the bull Audita tremendi, calling for mobilisation.

Monarchs such as Richard I of England and Philip Augustus of France were pressured into taking the cross.

In Outremer, surviving leaders hoped Western aid would restore their position, but the loss also revealed their dependence on European intervention for survival.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Name two problems faced by Outremer in the years leading up to the Battle of Hattin (1187).

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each valid problem identified.

Acceptable answers include:

Political disunity between factions (e.g., Guy of Lusignan vs. Raymond of Tripoli).

Weakness of Baldwin IV due to leprosy.

Limited manpower and reliance on reinforcements from Europe.

Dependence on the Military Orders with occasional conflicts of policy.

Geographical vulnerability between stronger Muslim states.

(Maximum 2 marks.)

Question 2 (6 marks):

Explain two reasons why Frederick Barbarossa’s expedition during the Third Crusade failed to reach Jerusalem.

Mark Scheme:

Up to 3 marks for each well-explained reason.

Answers should identify and explain causes, not just list them.

Indicative content may include:

Death of Frederick Barbarossa (up to 3 marks): The Emperor drowned in the River Saleph in 1190, which caused a collapse in morale, widespread desertions, and loss of effective leadership.

Geographical and logistical challenges (up to 3 marks): The overland march through hostile Anatolia was difficult, with supply shortages, heat, and Turkish attacks undermining the army before it reached the Levant.

Relations with Byzantium (up to 3 marks): Tense diplomacy with Isaac II Angelos slowed progress and bred suspicion, making the expedition less effective.

Maximum 6 marks: reward depth of explanation over breadth of points.

(Answers must cover two reasons. If only one reason is explained fully, maximum 3 marks can be awarded.)