OCR Specification focus:

‘The succession; administrative methods, inheritance and priorities by 1519; reliance on foreigners.’

The succession of Charles I in 1516 marked a critical juncture in Spanish history, with complex challenges of inheritance, governance, and the balancing of foreign influences.

The Succession of Charles I

The death of Ferdinand of Aragon in 1516 left his grandson, Charles of Habsburg, heir to the crowns of Castile and Aragon. Charles, only 16 years old, had been raised in the Netherlands under Burgundian traditions. This upbringing meant that he was unfamiliar with Spanish customs, politics, and language, making his succession controversial. Many Spaniards had expected Ferdinand’s younger son-in-law, Cardinal Cisneros, to act as regent until Charles matured, but Charles asserted his claim immediately.

Inheritance and Composite Monarchy

Charles inherited one of the largest and most diverse political units in Europe:

Spain (Castile and Aragon): Each with its own laws, institutions, and traditions.

The Netherlands and Burgundy: Prosperous northern territories with strong urban economies.

Claims to Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia: Strengthening his Mediterranean position.

The prospect of the Holy Roman Empire: Realised in 1519 when Charles became Emperor.

Composite Monarchy: A political structure where one monarch rules over several distinct kingdoms, each retaining its own laws and institutions.

Charles’s inheritance created a composite monarchy, requiring careful administrative management to hold together regions with different expectations of royal authority.

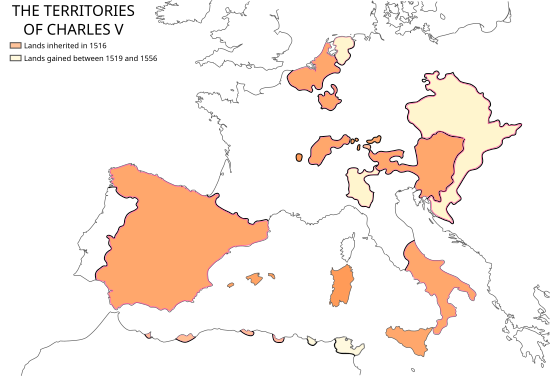

By 1519, Charles’s inheritance created a composite monarchy linking Castile, Aragon–Naples–Sicily, and the Burgundian Netherlands.

Map of Charles V’s European territories. Orange shows lands inherited at accession. Source

Administrative Methods

Charles relied heavily on Burgundian methods of government, favouring centralised royal councils and the use of trusted advisers. However, Spanish political traditions demanded negotiation with the Cortes (parliaments) and respect for local privileges (fueros). This created tensions between Charles’s desire for efficiency and Spain’s insistence on traditional rights.

Use of Royal Councils

Charles employed councils to manage specific areas:

Council of Castile: Oversaw domestic governance.

Council of Aragon: Managed Aragonese affairs, though more loosely structured.

Council of Finance: Administered revenue collection.

Council of the Indies (later established in 1524): Managed overseas territories, though beyond the initial focus of 1519.

These councils allowed Charles to maintain direct oversight of his multiple realms but also risked alienating the Spanish nobility, who were accustomed to a more participatory role.

Reliance on Foreigners

One of the most controversial aspects of Charles’s early rule was his dependence on foreign advisers, particularly from Burgundy and Flanders. Key positions were given to non-Spaniards, such as William de Croÿ, who became Archbishop of Toledo in 1517 despite lacking ties to Spain.

This reliance on foreigners generated resentment among the Castilian elite:

Spanish nobility felt excluded from influence.

Urban elites resented the export of wealth to Charles’s northern territories.

Opposition culminated in the Comunero Revolt (1520–1521), where Castilian towns protested against foreign dominance and Charles’s disregard for traditional governance.

Comunero Revolt: A major uprising of Castilian towns (1520–1521) protesting Charles’s reliance on foreigners and his neglect of Castilian interests.

In 1516–1519 the nineteen-year-old Charles I governed with a Burgundian household, unsettling the Castilian Cortes.

Barend van Orley, Portrait of Charles V (1519–1520). The Golden Fleece badge and Burgundian emblems signal his Netherlandish court culture at the moment of accession and the 1519 imperial bid. Use it to illustrate the narrative of reliance on foreigners.

Priorities by 1519

Charles’s priorities at the outset of his reign were shaped by his vast inheritance:

Securing legitimacy in Spain: Winning over the Castilian and Aragonese elites was crucial.

Financing his ambitions: Raising revenue to support his bid for Holy Roman Emperor required heavy taxation.

Balancing regional tensions: Reconciling the divergent expectations of Castile and Aragon demanded sensitive administration.

Strengthening dynastic authority: Following the example of Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles sought to reinforce the monarchy as the central authority.

By 1519, Charles’s immediate concern was securing the imperial crown. This distracted him from domestic consolidation in Spain and deepened resentment at the heavy financial demands imposed to fund his election campaign. The use of Castilian resources to pursue external goals highlighted a persistent tension in his reign: Spain as both a kingdom in its own right and as the foundation of a wider Habsburg empire.

Financial Administration

Charles’s government drew heavily on Castile’s relative wealth:

Alcabala (sales tax) formed the backbone of royal income.

Extraordinary subsidies were demanded from the Cortes of Castile.

Aragon, by contrast, contributed far less, reflecting its weaker economy and stronger defence of local privileges.

This fiscal imbalance gave Castile a dominant role within Charles’s empire but also placed significant strain on its towns and urban elites.

Heraldry and titles signalled a personal union of Crowns rather than a unitary state.

Ornamented royal arms used 1516–1518. The quartering displays the dynastic composite (Iberian and Burgundian-Austrian elements) with Burgundian eagle and Spanish lion supporters. Source

Legacy of the Early Succession

The succession of Charles I illustrates the continuity of the “New Monarchy” established by Ferdinand and Isabella but also reveals the difficulties of integrating Spain into a European-wide Habsburg empire. His reliance on foreigners, imposition of financial burdens, and neglect of Spanish traditions laid the groundwork for future unrest, even as his administrative methods aimed at consolidating royal authority.

FAQ

Charles was raised in the Burgundian Netherlands, where court culture emphasised formality, ceremony, and centralised councils. This shaped his preference for Burgundian-style administration.

However, it created a cultural and political gap when he arrived in Spain, as he spoke little Spanish and was unfamiliar with its institutions. Many Spaniards perceived him as an outsider, which weakened his legitimacy in the early years.

Cardinal Cisneros acted as regent of Castile until Charles’s arrival in 1517.

He sought to maintain stability and prepare for Charles’s succession.

His regency was limited in effectiveness because he lacked strong support from nobles, many of whom were cautious about backing a foreign-raised king.

Cisneros died shortly after Charles’s arrival, leaving the young monarch without an experienced Spanish mentor.

The Cortes were initially hesitant, as Charles requested subsidies to fund his imperial election campaign.

They eventually granted funds but extracted promises that Spanish interests would not be ignored.

This fragile compromise fuelled resentment when wealth was diverted to northern Europe, laying foundations for later unrest.

Charles awarded high offices, including bishoprics and court positions, to foreign favourites from Burgundy and Flanders.

Spaniards saw this as exploitation of their kingdom’s wealth and opportunities.

The appointment of William de Croÿ as Archbishop of Toledo was particularly offensive, as it placed a foreign youth in the most prestigious ecclesiastical role in Spain.

Castile and Aragon had distinct traditions of governance.

Castile provided the majority of revenue and accepted a stronger central authority, which Charles exploited.

Aragon defended its fueros (local privileges) and resisted attempts at centralisation, forcing Charles to respect its autonomy.

This imbalance contributed to Castile’s greater integration into Charles’s empire, while Aragon remained more loosely connected.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Who did Charles I of Spain rely on most heavily for advice in the early years of his reign, and why did this cause resentment in Castile?

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that Charles relied heavily on foreign/Burgundian advisers.

1 mark for explaining why this caused resentment, e.g. because Castilian nobles felt excluded or wealth and influence flowed abroad.

Question 2 (6 marks):

Explain how Charles I’s inheritance in 1516–1519 shaped his administrative priorities.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks: Limited or generalised description of Charles’s inheritance, e.g. “he ruled over many lands.”

3–4 marks: Clear explanation of how his composite monarchy (Castile, Aragon, Burgundian Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, Sardinia) created administrative challenges. Some reference to the need for councils or respect for local privileges.

5–6 marks: Developed explanation that links the vast inheritance directly to Charles’s administrative priorities by 1519. This may include:

the necessity to use royal councils to manage diverse territories,

the reliance on Castile’s wealth and taxation for imperial ambitions,

the importance of securing legitimacy and balancing the different laws and traditions across his realms.

Maximum marks require both description of inheritance and clear analytical links to administration.