OCR Specification focus:

‘foreign policy and the growing demand for war by 1915.’

Italy’s foreign policy between 1896 and 1915 shaped its path into war, balancing great power ambitions, domestic pressures, and shifting European alliances.

Italy’s Position in Europe by 1896

Italy in 1896 was a newly unified state facing internal weakness and external insecurity. Its status as a great power was fragile. Despite joining the Triple Alliance (1882) with Germany and Austria-Hungary, Italy remained mistrustful of Austrian control over Trentino and South Tyrol, areas claimed under irredentism. Italy therefore pursued a dual policy, tied formally to Germany and Austria, but cautiously engaging with Britain and France to safeguard its Mediterranean and colonial ambitions.

The Triple Alliance and Italian Interests

The Triple Alliance

The Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy) was a defensive military pact. Italy’s motivation was largely to prevent isolation.

Italy was promised military support if attacked by France.

However, Austria-Hungary’s occupation of territory Italy desired created constant tension.

A labelled map of European military alliances on the eve of war in 1914, showing Italy within the Triple Alliance opposite the Triple Entente. This clarifies the strategic context in which Italian decision-makers weighed neutrality against intervention. The map includes neutral states for comparison. Source

Italy’s Dual Policy

Italy’s leaders, particularly under Giovanni Giolitti, followed a pragmatic foreign policy:

Maintaining the alliance with Germany and Austria for security.

Secretly cultivating ties with France and Britain to avoid dependence.

Securing recognition of Italy’s colonial claims, particularly in North Africa.

This dual approach allowed flexibility, but also revealed the lack of firm direction in Italian foreign affairs.

Colonial Ambitions and International Standing

Italy’s pursuit of an empire was crucial to its self-image as a great power.

Abyssinia (1896): The crushing defeat at Adwa exposed Italy’s weakness, damaging prestige.

Tripoli Campaign (1911–1912): Italy seized Libya from the Ottoman Empire after war in North Africa. Though militarily costly, it was hailed domestically as proof of Italy’s great power status.

The Tripoli campaign fostered nationalist enthusiasm but also fuelled opposition:

Nationalists saw it as vindication of imperial ambition.

Socialists condemned it as capitalist exploitation, leading to mass strikes.

Nationalism, Irredentism, and Domestic Pressures

Nationalism and Irredentism

Irredentism referred to the demand for the unification of Italian-speaking populations under foreign rule (notably Trentino, South Tyrol, Dalmatian coast).

Nationalists demanded confrontation with Austria-Hungary to recover these territories.

Irredentist propaganda painted neutrality as weakness and dishonour.

Irredentism: The nationalist movement advocating for Italy to annex territories with Italian-speaking populations still under Austrian or other foreign rule.

Socialist Opposition

The Italian Socialist Party (PSI) strongly opposed militarism. It promoted international solidarity and argued that Italy should focus on solving domestic inequalities. This produced strikes and protests, particularly during the Libyan war.

Nationalist Agitation

The rise of Enrico Corradini’s Nationalist Association (ANI) in 1910 added new pressure. Nationalists demanded:

Expansion abroad for resources and markets.

Aggressive stance against Austria-Hungary.

War as a means of national regeneration.

The Road to War, 1911–1915

The Balkan Crises and Rising Tensions

The Balkan Wars (1912–1913) threatened European stability. Italy feared being marginalised as Austria-Hungary and Russia vied for influence. Nationalists exploited this insecurity, demanding Italy join the scramble for influence.

Relations with the Great Powers

With Austria-Hungary: Relations were poor, as Austria obstructed Italian influence in the Balkans.

With Britain and France: Italy cultivated secret assurances of support for Mediterranean interests.

With Germany: Italy remained formally allied but wary of being dragged into Germany’s conflicts.

The Growing Demand for War

By 1914, Italy was divided:

Neutralists (Giolitti, Socialists, Catholic moderates) wanted to stay out of European conflict, citing economic weakness and domestic unrest.

Interventionists (Nationalists, many Liberals, radical Republicans) demanded war to complete national unification and secure great power status.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 triggered the First World War. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Italy initially declared neutrality, citing that the Triple Alliance was defensive.

The Intervention Crisis of 1914–1915

The neutrality of 1914 was deeply contested. Italy faced growing political agitation:

Nationalists denounced neutrality as cowardice.

Socialists staged mass protests against war.

King Victor Emmanuel III and interventionist ministers pressed for Italy to seize the opportunity to expand.

Leopoldo Metlicovitz’s Finalmente!! portrays Trento and Trieste imploring Italia, encapsulating the emotional force of irredentism and the interventionist campaign of 1914–15. The allegorical style dramatises pressure for war to “redeem” Italian-speaking lands. Source

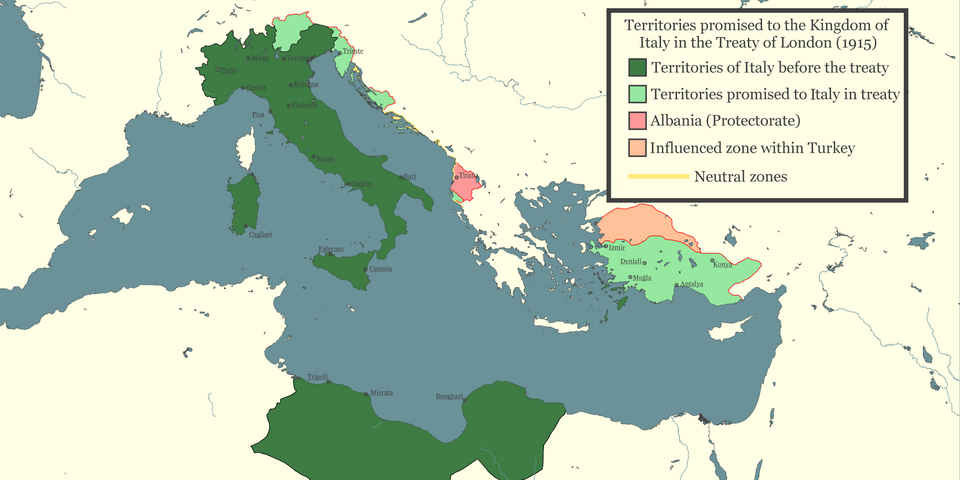

The Treaty of London (April 1915)

Italy secretly negotiated with the Entente Powers (Britain, France, Russia) and signed the Treaty of London, promising to join the war against Austria-Hungary.

Map of the territories pledged to Italy by the Treaty of London (April 1915), including Trentino–South Tyrol, the Istrian peninsula, specified Dalmatian areas, and the Dodecanese. This visualises the concrete incentives that swayed Italy’s move from neutrality to intervention. Source

In return, Italy was promised:

South Tyrol and Trentino-Alto Adige.

Istrian peninsula.

Influence in Dalmatian coast and Dodecanese islands.

Colonial compensation in Africa.

This secret treaty marked the culmination of nationalist pressure and the triumph of pro-war forces over Giolitti’s neutralist stance.

Conclusion of the Pre-War Period

By May 1915, Italy entered the First World War on the side of the Entente. The decision reflected:

Longstanding irredentist demands.

Nationalist agitation for imperial expansion.

Disillusionment with Austria-Hungary and the limitations of the Triple Alliance.

The lure of promised territorial rewards in the Treaty of London.

Thus, foreign policy and domestic agitation combined to push Italy into the war, setting the stage for the political transformations that followed.

FAQ

Italy’s foreign policy was shaped by competing priorities. On one hand, it relied on the Triple Alliance for security, but on the other, it distrusted Austria-Hungary because of irredentist claims.

Economic weakness and limited military capacity also forced Italian leaders to avoid long-term commitments. Governments often prioritised short-term diplomatic manoeuvres rather than sustained strategy, creating inconsistency.

Giolitti advocated neutrality, believing Italy was unprepared economically and militarily for a major war. He saw neutrality as a means to preserve stability while extracting concessions from either side.

Giolitti also argued that war would deepen class conflict, strengthen Socialists, and undermine Italy’s fragile democracy. His caution was influential but eventually outmanoeuvred by pro-war forces.

Nationalist groups produced pamphlets, posters, and rallies to mobilise public opinion.

Propaganda portrayed neutrality as dishonourable.

Irredentist imagery depicted Trentino and Trieste as “unredeemed” Italian lands.

Interventionist writers like Enrico Corradini linked war to national strength, unity, and empire.

This use of symbolism and mass mobilisation was critical in pushing undecided Italians towards supporting intervention.

Italy’s alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary was defensive, but Austrian control of Italian-speaking territories created permanent tension.

The alliance also failed to protect Italy’s Mediterranean ambitions, as Austria and Germany prioritised Central Europe. Italy’s leaders, therefore, treated the alliance as insurance against isolation rather than a trusted partnership.

The Balkan Wars (1912–13) highlighted Italy’s vulnerability to being sidelined by Austria-Hungary and other powers.

Austria’s expansion in the Balkans clashed directly with Italian ambitions.

Italy feared being excluded from regional negotiations and losing influence in the Adriatic.

Nationalists used these fears to argue that Italy needed decisive military action to assert itself.

These developments intensified the sense of urgency among interventionists prior to 1915.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Identify two territories promised to Italy in the Treaty of London (1915).

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each correct territory identified.

Acceptable answers include:

Trentino-Alto Adige (South Tyrol)

Istrian Peninsula

Dalmatian Coast (specified areas)

Dodecanese Islands

Colonial compensation in Africa

Maximum: 2 marks.

Question 2 (6 marks):

Explain why Italian nationalists demanded intervention in the First World War by 1915.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 2 marks for each well-developed reason, linked clearly to nationalist motivations.

Indicative content may include:

Irredentism (Trentino, South Tyrol, Istria, Dalmatian coast): Nationalists argued war would complete national unification. (Up to 2 marks)

Great Power status: Nationalists believed war would assert Italy’s strength and elevate its international standing. (Up to 2 marks)

Domestic prestige and regeneration: Interventionists argued war would unify and strengthen Italy, countering Socialist opposition and internal weakness. (Up to 2 marks)

Maximum 6 marks.

Award marks for valid alternatives if substantiated with explanation.