OCR Specification focus:

‘the weaknesses of the post-war governments, the mutilated victory, reactions to the Paris Peace conference and the seizure of Fiume by d’Annunzio; electoral pact 1921 and the March on Rome.’

Italy after the First World War faced immense instability. Weak governments, discontent with the peace settlement, and violent political movements shaped the transition from liberal democracy to Mussolini’s seizure of power.

Weaknesses of the Post-War Governments

Political Instability

The post-war years saw a succession of weak coalition governments unable to maintain authority or stability. Prime ministers such as Nitti, Giolitti, and Bonomi lacked majority support, and governments often collapsed within months. This fragility reflected the fractured Italian political system and the inability of liberal politicians to adapt to new pressures.

Reliance on unstable coalitions

Frequent changes of prime minister

Failure to address mass discontent

Social and Economic Turmoil

The war had left Italy with a heavily damaged economy and deep social divisions. Inflation, rising unemployment, and food shortages eroded trust in the liberal state.

Industrial unrest surged with strikes across the north.

Agrarian unrest grew in the south, where peasants occupied land illegally.

Veterans returned to find limited employment opportunities, creating bitterness and political radicalisation.

The Mutilated Victory

Disappointment with the Paris Peace Conference

Italy entered the First World War in 1915 under the Treaty of London, expecting territorial rewards. However, the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 failed to meet these ambitions fully.

Mutilated Victory: A phrase popularised by Gabriele d’Annunzio to describe Italian disappointment at the limited territorial gains awarded after the First World War.

Italy gained South Tyrol, Trentino-Alto Adige, and Istrian Peninsula but was denied Dalmatian territory and significant colonial rewards. Most controversially, Italy was denied control of the port city of Fiume and parts of Dalmatia promised under secret treaties. The sense of betrayal weakened liberal governments, fuelling nationalist resentment.

Impact on Nationalism

The failure at Paris emboldened nationalist critics who accused liberal leaders of betraying Italy. This provided fertile ground for the rise of radical alternatives such as Fascism.

Nationalist press denounced the government as cowardly.

Veterans’ groups, particularly the Arditi, rallied around the theme of betrayal.

Liberal politicians appeared incapable of defending Italy’s national interests.

The Seizure of Fiume

D’Annunzio’s Intervention

In September 1919, poet and nationalist Gabriele d’Annunzio led around 2,000 ex-soldiers in the occupation of Fiume in what became known as the March on Fiume. This was a dramatic defiance of international agreements and the Italian government.

D’Annunzio, beside engineer Carlo Alessandro Conighi, raises the Italian flag in Fiume in 1920. The occupation symbolised nationalist defiance of the Paris settlement. Source

The event lasted for 15 months.

It became known as the “Regency of Carnaro”, run under d’Annunzio’s flamboyant leadership.

Though eventually suppressed by the army, it highlighted the government’s weakness and emboldened future Fascist methods.

Irredentism: A nationalist belief that Italy should annex all territories inhabited by ethnic Italians or historically linked to Italy.

D’Annunzio’s actions demonstrated that bold, extra-parliamentary action could humiliate liberal governments. This precedent was not lost on Mussolini.

The Electoral Pact of 1921

Origins of the Pact

By 1921, Italian politics was paralysed. Prime Minister Giolitti attempted to stabilise the situation by forming an electoral pact with Mussolini’s Fascists. The aim was to harness their popularity and violence to secure votes against the growing Socialist threat.

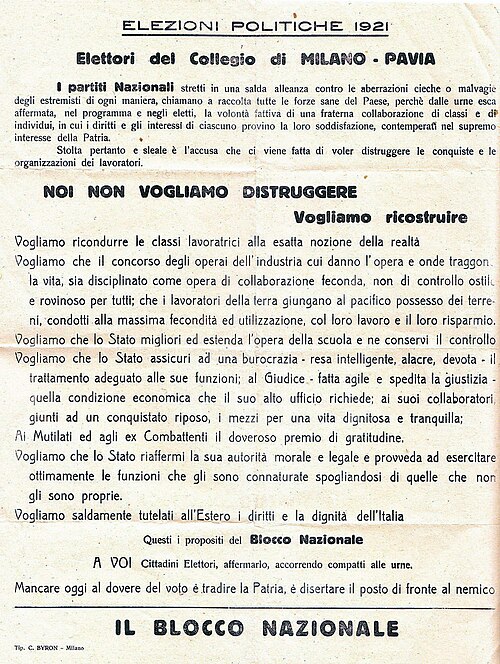

“Giolitti’s electoral pact (Blocco Nazionale, 1921) aligned liberals, conservatives, nationalists and Fascists to isolate Socialists and the Popolari.”

Original leaflet for the Blocco Nazionale in Milan during the 1921 election. It exemplifies how the coalition presented itself to voters and underscores its anti-socialist pitch. Source

Officially called the “National Bloc”, it was an alliance of liberals, conservatives, and Fascists.

The pact gave legitimacy to Mussolini’s movement.

Fascists gained 35 seats in parliament, ensuring their voice in national politics.

Consequences

The pact backfired on Giolitti. Instead of marginalising the Fascists, it provided them with parliamentary respectability and a platform for future power. It also deepened divisions within liberal ranks.

The March on Rome

Causes of the March

By late 1922, Fascism had grown as a mass movement supported by industrialists, landowners, and sections of the middle class. Its squadristi (paramilitary squads) used violence to break strikes and intimidate opponents. The liberal state appeared powerless.

Weak liberal governments provided no strong leadership.

Economic crises continued, with inflation and unemployment fuelling unrest.

Fascists projected themselves as the only force capable of restoring order.

The Event

In October 1922, Mussolini organised the March on Rome, a demonstration of Fascist power. Around 30,000 Blackshirts converged on the capital. The government considered declaring martial law but King Victor Emmanuel III refused to sign the decree.

“On 28–30 October 1922, Blackshirts advanced on Rome while Vittorio Emanuele III refused to sign a state of siege, and Mussolini was invited to form a government.”

The king’s refusal was decisive, showing the monarchy’s fear of civil war.

Instead, Mussolini was invited to form a government.

The march became a mythic foundation moment of the Fascist regime.

March on Rome: A mass mobilisation of Fascist supporters in October 1922 that pressured the king into appointing Mussolini as prime minister.

Consequences of the March

The March on Rome marked the collapse of Italy’s liberal system. Mussolini, appointed prime minister on 29 October 1922, began the transition from parliamentary politics to dictatorship.

Fascism moved from fringe to power.

Liberalism discredited as weak and divided.

The monarchy revealed its unwillingness to defend constitutional government.

FAQ

Many veterans returned from the war disillusioned and unemployed, fuelling anger at the liberal state. Groups like the Arditi felt betrayed by the “Mutilated Victory” and sought more radical political solutions.

Veterans’ associations often acted as recruitment pools for nationalist and Fascist movements, providing disciplined men accustomed to violence and camaraderie. This gave political extremism a powerful militant base.

D’Annunzio’s occupation of Fiume showed that dramatic, extra-parliamentary action could gain mass attention and embarrass the government.

Mussolini observed how spectacle, symbolism, and militarised politics could mobilise public support.

Elements like marching columns, mass rallies, and the cult of a charismatic leader were later incorporated into Fascist strategy.

Landowners feared socialist land seizures, while industrialists feared strikes and factory occupations.

Both groups turned to Fascist squads to protect property and suppress labour unrest. Financial backing from these elites strengthened the Fascist movement, making it more than a fringe paramilitary force.

Italy used proportional representation, which allowed small but organised groups to secure parliamentary seats.

Through the Blocco Nazionale, Fascists were given legitimacy by allying with liberals. Despite only modest nationwide support, this alliance ensured Fascists gained a foothold in parliament and national politics.

The king feared that military resistance to the Blackshirts might trigger civil war or split the army, as many officers were sympathetic to Fascism.

He also distrusted existing liberal governments and hoped Mussolini could restore stability. His refusal effectively handed power to the Fascists without a serious fight.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

What is meant by the term “Mutilated Victory” in the context of post–First World War Italy?

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying that it referred to Italian dissatisfaction with the outcomes of the Paris Peace Conference.

1 mark for explaining that Italy did not receive all the territorial rewards promised in the Treaty of London, such as Dalmatia or Fiume.

Question 2 (6 marks):

Explain how the weaknesses of Italy’s post-war governments contributed to Mussolini’s rise to power by 1922.

Mark Scheme:

Up to 2 marks for explaining the instability of coalition governments (e.g., frequent changes of prime minister, reliance on shifting alliances).

Up to 2 marks for linking failure to address economic and social unrest (e.g., strikes, unemployment, peasant land seizures) with public disillusionment in liberal leaders.

Up to 2 marks for showing how these weaknesses allowed the Fascists to present themselves as a strong alternative capable of restoring order.

Level descriptors:

1–2 marks: General description of instability or problems, limited explanation of link to Mussolini.

3–4 marks: Clear explanation of at least two weaknesses of governments, some linkage to Mussolini’s rise.

5–6 marks: Developed explanation of multiple weaknesses, with direct analysis of how these created opportunities for Mussolini and the Fascists.