OCR Specification focus:

‘Richard’s quarrel with Gaunt; the influence of de la Pole and de Vere; war with France and Scotland 1385–1386.’

Richard II’s personal rule between 1380 and 1388 was marked by factional rivalries and difficult foreign wars. The years 1385–1386 were especially turbulent, revealing the king’s strained relations with leading nobles and testing his authority in the face of military failure abroad and mounting political divisions at home.

Richard’s Quarrel with John of Gaunt

Richard II’s relationship with his uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, had always been tense. Gaunt had exercised enormous influence during Richard’s minority, and by the mid-1380s Richard was eager to assert his independence. Gaunt’s dominance was perceived as overbearing, and the young king resented his uncle’s position as the wealthiest and most powerful magnate in the realm.

Engraved portrait of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, a central actor in the political rifts of 1385–1386. As a post-medieval engraving, it is not contemporary, but it provides visual context for this key personality in the factional politics of Richard II’s reign. Source

Background to the Quarrel

John of Gaunt’s ambition and continental interests made him a divisive figure.

His expedition to Spain in 1386, pursuing his claim to the Castilian throne, left Richard without his uncle’s experienced counsel and military resources.

Richard interpreted Gaunt’s departure as both a liberation and a challenge, providing him an opportunity to strengthen his own authority, yet also leaving him politically exposed.

Tensions with Royal Authority

Richard viewed Gaunt’s power as a direct threat.

Gaunt had long been criticised for his failure in France and for his unpopularity with Londoners.

Richard suspected his uncle might undermine his rule or rival his legitimacy.

The king’s mistrust further exacerbated factional divisions at court, encouraging the rise of new favourites.

The Influence of Michael de la Pole and Robert de Vere

The growing role of Michael de la Pole and Robert de Vere was central to Richard’s politics in these years.

Michael de la Pole

Michael de la Pole, son of a Hull merchant, rose through royal service to become Chancellor of England in 1383.

His advancement symbolised the increasing influence of non-traditional aristocrats in government.

He advocated for ambitious royal policies but was blamed for financial mismanagement and military failure.

Chancellor: The king’s chief minister responsible for government administration, royal finances, and the issue of official documents.

De la Pole’s prominence attracted hostility from the nobility, who accused him of self-enrichment and corrupting Richard’s court.

Robert de Vere

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford and later Duke of Ireland, was Richard’s closest companion.

His elevation to the new title of Duke of Ireland in 1386 symbolised Richard’s favouritism.

#######################################

Coat of arms of Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland, quartering the de Vere star with the royal augmentation of three crowns on blue within a silver bordure granted under Richard II. This heraldic visual reflects Richard’s political favouritism and de Vere’s controversial rise in 1386. Source

De Vere’s influence extended beyond politics into the king’s personal life, generating resentment among the traditional nobility.

Richard’s reliance on these men deepened the rift with older, established magnates. Their prominence represented a shift towards personal monarchy, where loyalty to the king outweighed lineage or traditional authority. This shift alienated figures such as Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, and Henry Bolingbroke, son of Gaunt.

War with France and Scotland 1385–1386

While factional rivalries destabilised domestic politics, foreign wars further weakened Richard’s authority.

The Scottish Campaign of 1385

Richard II led an expedition to Scotland in 1385, accompanied by John of Gaunt and other nobles.

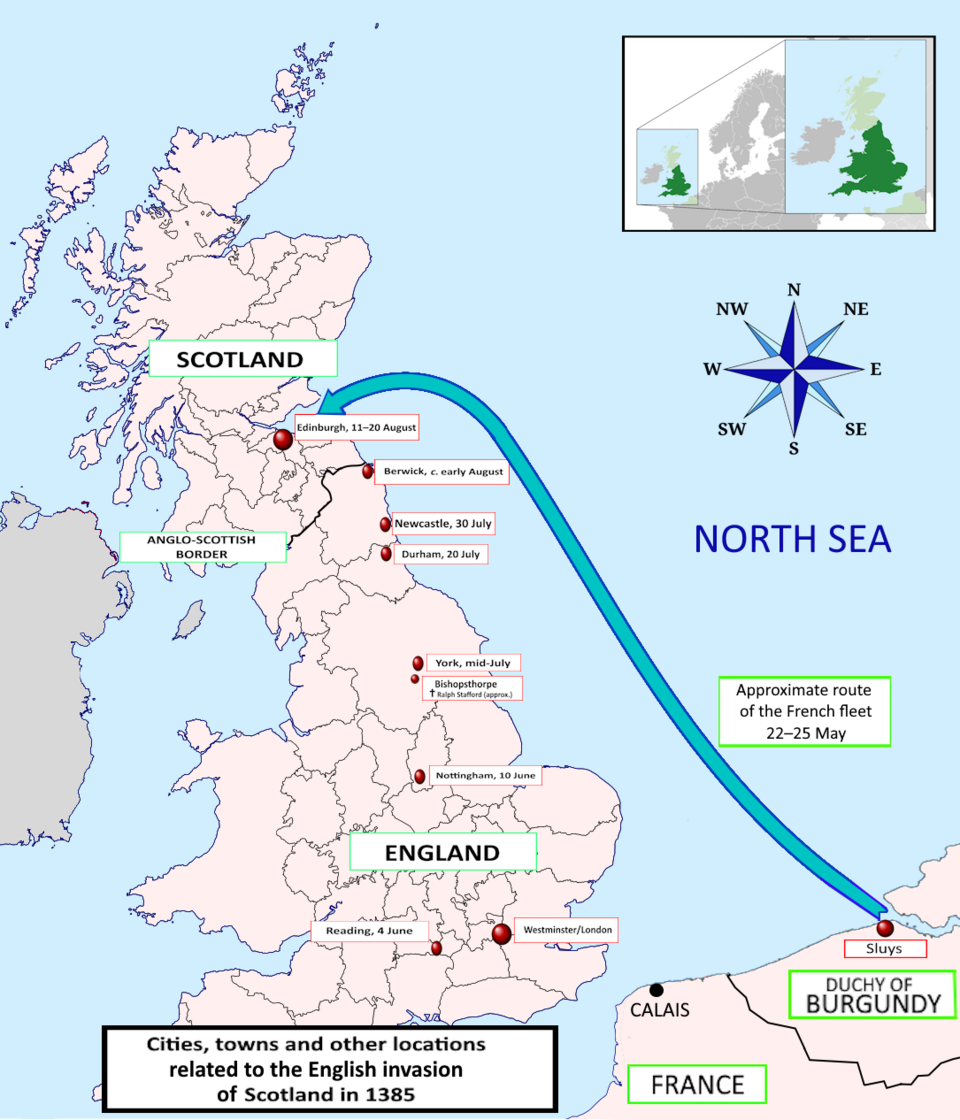

Map showing the route of Richard II’s army into Scotland in 1385, with principal staging points and border regions marked. This visual contextualises the geography of the indecisive campaign. Source

The campaign was poorly coordinated: the Scots avoided pitched battle, using scorched-earth tactics to deny resources.

Richard’s army advanced as far as Edinburgh but achieved no decisive victory.

Mutual suspicion between Richard and Gaunt undermined command, leading to strategic paralysis.

The army eventually withdrew, leaving the campaign widely regarded as a failure.

Renewed French Threats

France intensified attacks on England during these years, exploiting the divisions at Richard’s court.

In 1385–1386, French forces threatened invasion, with a major fleet gathering at Sluys.

The French also supported Scotland, creating a two-front problem for Richard.

English naval defences were overstretched, and morale suffered after years of inconclusive conflict.

Scorched-earth tactics: A military strategy where retreating forces destroy crops, livestock, and infrastructure to deny resources to the enemy.

The dual pressure from France and Scotland revealed England’s military weakness and highlighted the need for more effective leadership, which Richard’s critics argued he lacked.

Political Consequences of Faction and War

The years 1385–1386 left Richard politically vulnerable.

His quarrel with Gaunt destabilised the balance of royal power.

The elevation of de la Pole and de Vere alienated leading nobles, who saw them as unworthy favourites.

Military failures abroad eroded confidence in the king’s ability to defend the realm.

The financial burden of war increased tensions with parliament, foreshadowing greater conflict in the Wonderful Parliament of 1386, where de la Pole would face impeachment.

Layers of Discontent

Nobility: Resentful of royal favourites displacing their influence.

Commons in Parliament: Critical of taxation and poor military returns.

Londoners: Suspicious of Richard’s household expenditure and his disregard for traditional governance.

The crisis of 1385–1386 thus marked a turning point, exposing Richard’s fragile authority and deepening factional rivalries that would culminate in the challenge of the Lords Appellant.

FAQ

Gaunt was not only the king’s uncle but also the wealthiest magnate in England, with vast estates and a large retinue. Their quarrel unsettled the political order because many nobles relied on Gaunt’s patronage and leadership. When Richard clashed with him, those loyalties fractured, fuelling rival factions.

Parliament had repeatedly granted taxation to fund campaigns, but the lack of success in Scotland damaged trust in Richard’s leadership. Many MPs viewed the Scottish expedition as a costly failure with little strategic benefit. This financial frustration hardened criticism of Richard’s governance and provided ammunition against his favourites.

Contemporary chroniclers, often sympathetic to the nobility, painted de Vere and de la Pole as greedy and corrupt.

De la Pole was accused of self-enrichment through his office as Chancellor.

De Vere was depicted as reckless, his rapid promotions seen as dishonourable.

These portrayals amplified hostility among nobles and the commons, undermining Richard’s defence of his favourites.

The French assembled a large fleet at Sluys, and rumours of invasion spread across southern England.

Coastal defences were weak, with limited naval resources to counter an attack.

Memories of earlier raids and the Hundred Years’ War heightened fears.

London merchants were especially anxious about the vulnerability of trade routes.

This threat made Richard’s military leadership seem inadequate and increased parliamentary pressure for reform.

Richard increasingly rewarded personal loyalty over noble tradition, visible in his reliance on de la Pole and de Vere.

By elevating de Vere to Duke of Ireland, Richard signalled that royal favour could outweigh bloodline.

De la Pole’s position as Chancellor demonstrated preference for competence in royal service rather than noble heritage.

This shift unsettled established magnates, who saw it as a direct challenge to the conventional hierarchy of governance.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two reasons why Richard II’s 1385 campaign in Scotland was unsuccessful.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each valid reason identified, up to 2 marks.

Acceptable points include:

The Scots avoided pitched battle (1 mark).

The Scots used scorched-earth tactics (1 mark).

Mutual suspicion and poor cooperation between Richard II and John of Gaunt (1 mark).

Poor strategic planning and lack of decisive action (1 mark).

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how Richard II’s reliance on favourites such as Michael de la Pole and Robert de Vere contributed to political tensions in 1385–1386.

Mark Scheme:

Award 1–2 marks for a basic description of Richard II’s favourites or their rise.

Award 3–4 marks for explanation of why their influence caused tensions, linking to opposition from nobles and parliament.

Award 5–6 marks for developed explanation with clear connections to factionalism, Gaunt’s strained relationship with the king, and the wider consequences for Richard’s authority.

Indicative content:

De la Pole rose from merchant background to Chancellor, seen as unworthy by nobility (1–2 marks).

Both de la Pole and de Vere accused of mismanagement and corrupt influence (1–2 marks).

Richard’s favouritism alienated established nobles, e.g. Gloucester and Bolingbroke, creating factions (1–2 marks).

The elevation of de Vere to Duke of Ireland in 1386 symbolised royal favouritism and further angered the aristocracy (1–2 marks).

This favouritism contributed to discontent that led directly into the Wonderful Parliament of 1386 (1–2 marks).