OCR Specification focus:

‘Richard’s concept of monarchy; the causes, events and results of the Peasants’ Revolt’

Richard II’s early reign reveals both an ambitious royal ideology and the explosive tensions of late fourteenth-century England. His notion of kingship and the dramatic Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 together shaped the fragile monarchy of the young king.

Richard II’s Concept of Monarchy

The Divine Right of Kings

Richard II believed strongly in the sacred nature of monarchy. He held that kings were appointed by God and therefore answerable only to Him.

Divine Right of Kings: The doctrine that monarchs derive their authority directly from God, not from the consent of the people or governing bodies.

This conviction was striking in a boy of just fourteen years old, and it set him apart from many of his contemporaries, who expected a king to rule in consultation with his nobles. Richard’s ideology stressed absolute royal authority, and this frequently clashed with traditional expectations of shared governance.

Royal Imagery and Ceremony

Richard placed great emphasis on the use of royal ceremony, symbolism, and court ritual. He sought to enhance the majesty of the crown by emphasising pageantry at events such as coronations and public appearances.

Interior panels of the Wilton Diptych showing Richard II kneeling before the Virgin and Child, attended by angels who wear his white hart device. The work embodies the divine right and ceremonial splendour central to his kingship. (Includes religious iconography not required by the syllabus, used here to clarify royal ideology.) Source

Tensions with Nobility

Richard’s rigid view of monarchy led to early disputes with his councillors and magnates. Many expected the young king to act as first among equals, relying on consensus within councils and parliaments. Instead, Richard preferred to assert his independence, a stance that later became one of the roots of discontent during his reign.

Background to the Peasants’ Revolt

Economic and Social Pressures

The Black Death (1347–1351) had drastically reduced England’s population, creating labour shortages. Surviving workers demanded higher wages and more freedom, but the Statute of Labourers (1351) attempted to freeze wages at pre-plague levels. Resentment grew steadily over subsequent decades.

Taxation and the Poll Tax

Military campaigns in France and Scotland were expensive, and the government relied on new forms of taxation. The Poll Tax of 1377 and two subsequent levies in 1379 and 1380 were particularly unpopular because they taxed individuals at a flat rate, regardless of income.

Poll Tax: A form of taxation levied on each adult individual at the same rate, without consideration of wealth or status.

The third Poll Tax of 1380, collected under harsh enforcement, became a major trigger for revolt.

Religious and Intellectual Influences

The teachings of John Wycliffe, who criticised the wealth of the Church and argued for scriptural authority, influenced popular discontent. Although Wycliffe himself did not lead rebellion, his ideas contributed to the atmosphere of unrest, encouraging common people to challenge established hierarchies.

The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381

Outbreak and Spread

The revolt began in Essex and Kent in May–June 1381. Sparked by violent resistance to tax collectors, it quickly escalated into a mass uprising. Rebel leaders such as Wat Tyler and the preacher John Ball gave voice to demands for freedom from serfdom, lower rents, and an end to oppressive laws.

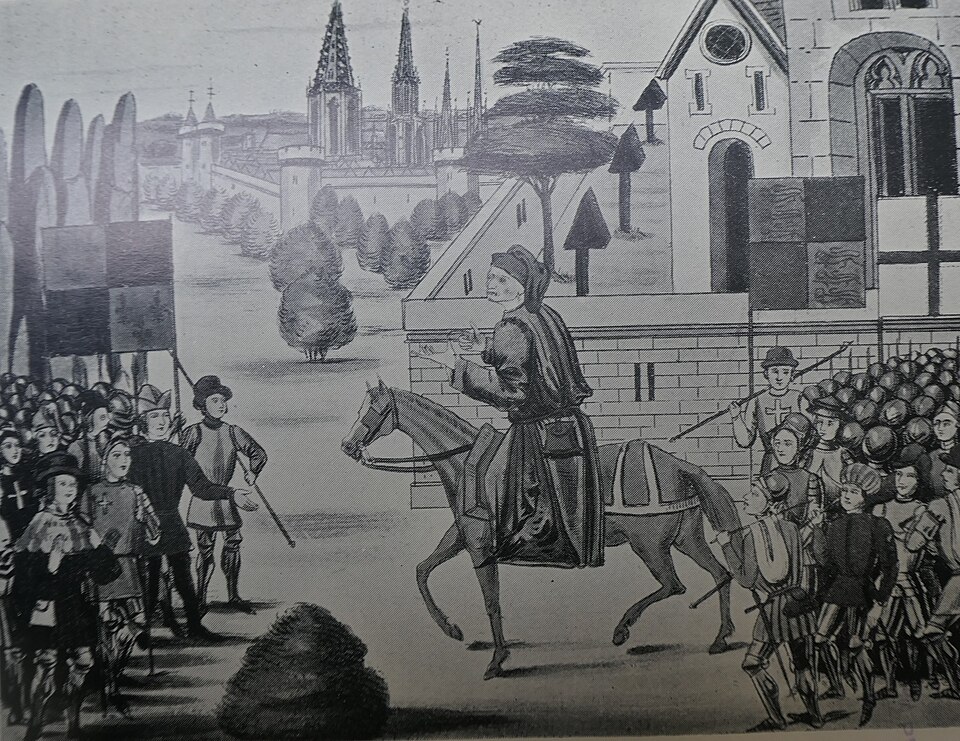

John Ball addresses armed commons in a scene from Froissart’s Chronicles. It highlights how preaching and popular rhetoric mobilised support for the rising. The broader setting reflects Ball’s role as a spokesperson for reformist grievances rather than a military leader. Source

March on London

Tens of thousands of rebels marched on London, where they:

Attacked symbols of government authority.

Executed officials such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury.

Destroyed legal records at the Inns of Court.

Presented demands for sweeping social change.

The rebels were initially welcomed by many Londoners, reflecting the capital’s own grievances.

Richard II’s Intervention

At just fourteen, Richard showed notable courage. He personally rode out to meet the rebels at Mile End on 14 June, where he agreed to charters promising freedom and reforms. This seemed to pacify the crowds.

However, the next day at Smithfield, negotiations collapsed. Wat Tyler was killed in a skirmish, and Richard calmed the crowd by stepping forward and declaring himself their leader.

#######################################

A 15th-century Froissart’s Chronicles miniature depicting the death of Wat Tyler amid the parley at Smithfield. Richard II is shown asserting royal authority before the assembled commons. The image clearly visualises the turning point that enabled the crown to suppress the revolt. Source

Results and Consequences of the Revolt

Short-Term Repression

Despite earlier promises, Richard and his government quickly reneged on concessions. Rebel leaders were executed, and the revolt was brutally suppressed across the counties. Thousands of peasants were fined or punished, and the immediate demands for freedom from villeinage were rejected.

Long-Term Social Impact

Although the government crushed the revolt, it revealed the fragility of serfdom. Within decades, villeinage declined rapidly, not through legislation but through gradual social and economic change. Landlords increasingly accepted free tenancies rather than bound labour, reflecting shifting realities.

Political Lessons for Richard II

The revolt shaped Richard’s self-image. He interpreted his handling of the crisis as a sign of divine favour and reinforced his belief in the sacredness of monarchy. Yet the violent outburst of popular anger also deepened distrust between the king, his nobility, and the commons. His reliance on absolutist ideology, partly rooted in the experience of 1381, would cause mounting tensions throughout his later reign.

Broader Significance

The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 was the first great popular rebellion in English history. While it failed to achieve its immediate goals, it:

Weakened the institution of serfdom.

Demonstrated the potential of mass protest.

Undermined faith in the ability of the monarchy to govern harmoniously.

Richard’s royal ideology and the revolt together highlight the tension between the ideals of absolute kingship and the realities of social and economic discontent in late medieval England.

FAQ

Richard was only fourteen during the revolt, which meant he had little direct governing experience. Despite this, his personal bravery at Mile End and Smithfield impressed many contemporaries.

His youth also allowed him to make promises he did not intend to keep, since responsibility for policy decisions rested with his advisers. This dual role — a figurehead of authority but not yet an independent ruler — shaped the course of events in 1381.

Though less prominent in chronicles, women were active participants. For example:

Women joined in attacking manorial records, which symbolised feudal obligations.

Some, like Johanna Ferrour, were identified as leaders in specific attacks in London.

Their involvement highlighted how discontent with taxation and social constraints cut across gender, even if male leaders dominated the narrative.

London was the kingdom’s political and economic hub. Rebels hoped that by controlling the capital, they could pressure the monarchy and government.

Londoners initially supported the rebels, opening the city gates and joining attacks on officials. However, the alliance was fragile. The urban elite later feared losing order and withdrew support, helping Richard to reassert control.

Ball preached a radical interpretation of equality. His famous phrase, “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”, challenged traditional hierarchies.

He promoted:

The rejection of serfdom.

Greater social equality rooted in Christian teaching.

The belief that divine authority did not justify aristocratic privilege.

This rhetoric resonated with common people but alarmed elites, reinforcing the perception of the revolt as dangerously subversive.

The revolt convinced Richard that he had a divine mission to rule independently, strengthening his sense of absolute kingship.

However, the nobility distrusted him more deeply afterwards, fearing his tendency to bypass counsel. This tension between royal authority and aristocratic expectation laid the groundwork for conflicts in the later years of his reign.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

In which year did the Peasants’ Revolt take place, and who was the key rebel leader killed at Smithfield?

Mark scheme:

1 mark for the correct year: 1381.

1 mark for identifying the rebel leader: Wat Tyler.

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain two reasons why the Poll Tax was a major cause of the Peasants’ Revolt.

Mark scheme:

Up to 3 marks for each valid reason explained.

Award 1 mark for identification of a reason, 2 marks for a basic explanation, and 3 marks for a developed explanation showing clear understanding of context.

Indicative content:

Unfair nature of the tax: It was a flat rate, meaning the poor paid the same as the wealthy, which created widespread resentment. (1 mark for identification, 2 for basic explanation, 3 for fully developed).

Frequency and harsh collection methods: The tax had been levied three times in quick succession (1377, 1379, 1380), and collectors often used force and intimidation, sparking violent resistance. (1 mark for identification, 2 for basic explanation, 3 for fully developed).