AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use limits to redefine or define a function’s value at a point of removable discontinuity so that the new function becomes continuous at that point.’

Removable discontinuities arise when a function fails continuity at a single point, yet nearby behavior suggests a natural value can be defined to restore continuity.

Understanding Removable Discontinuities

A removable discontinuity occurs when a function is discontinuous at a point, but the discontinuity can be eliminated by redefining the function’s value at that point. The graph of such a function typically shows a hole, indicating that the function is either undefined at the point or defined with a value that does not match the surrounding behavior.

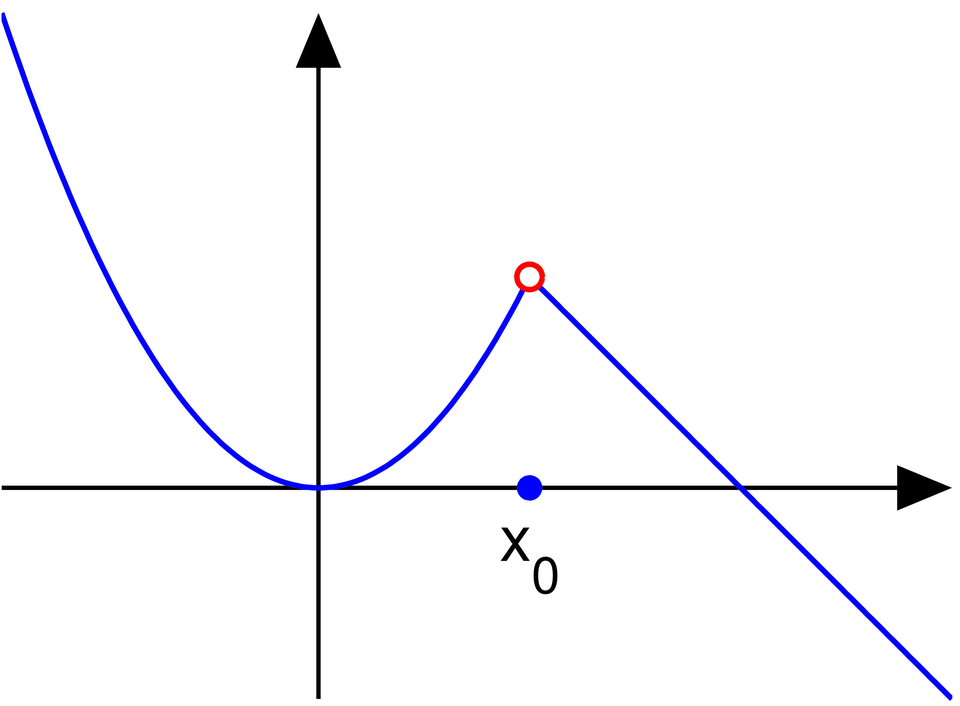

This diagram shows a classic removable discontinuity where the curve approaches a single height but the function value is missing, illustrated by the open circle marking the hole. Source.

This subsubtopic focuses specifically on how limits are used to repair this type of discontinuity, transforming a function that is not continuous at a point into one that is continuous there.

Removable Discontinuity: A discontinuity at x = c where the limit of the function as x approaches c exists, but the function value at c is either undefined or not equal to that limit.

The key feature is that the limit exists and is finite, meaning the function’s behavior near the point is well-behaved, even though the function itself fails continuity at that exact location.

The Role of Limits in Removing Holes

Limits are essential because they describe how a function behaves arbitrarily close to a point, independent of the function’s actual value at that point. When a removable discontinuity is present, the limit provides the value that the function is “trying” to take.

If the limit exists, it indicates that:

Values of the function near the point approach a single number.

The surrounding behavior is consistent from both sides.

The graph approaches a specific height, even if that height is missing or mismatched.

This limiting value becomes the natural candidate for redefining the function to restore continuity.

= x-value where the discontinuity occurs

= value the function approaches near x = c

The existence of this limit is what makes the discontinuity removable rather than permanent.

Redefining the Function Value

To remove a hole, the function must be redefined so that its value at the problematic point matches the limit.

This image illustrates a removable discontinuity where the limit corresponds to the open circle, while the function is incorrectly defined at the filled point; redefining the function to equal the limiting value “fills” the hole. Source.

This process does not change the function’s behavior anywhere else; it only adjusts the value at a single input.

The procedure relies on aligning all three conditions for continuity at a point:

The function must be defined at the point.

The limit at the point must exist.

The function value must equal the limit.

If the original function fails the third condition, redefining the function value resolves the issue.

Redefining a Function Value: Assigning a new value to a function at a specific point so that the function value equals the existing limit at that point, thereby restoring continuity.

This redefinition creates a new function that agrees with the original function everywhere except at the single point where the hole existed.

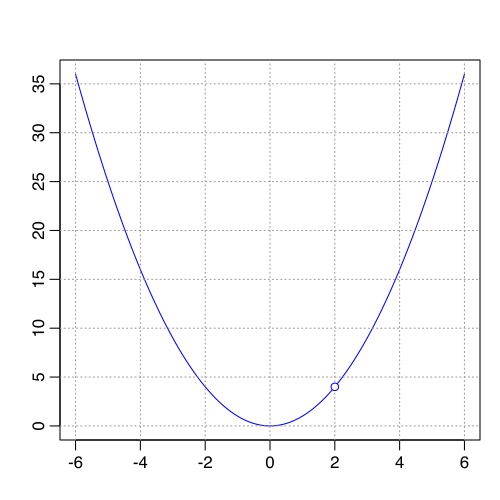

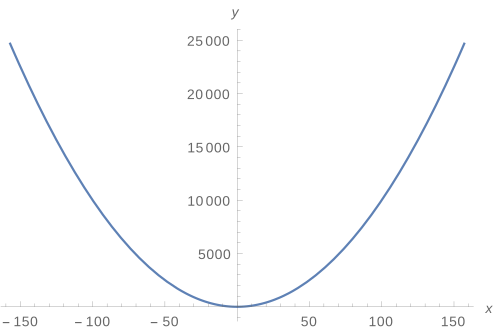

This continuous curve represents the visual outcome after redefining a missing function value so the graph becomes unbroken at the previously discontinuous point. Source.

When Redefinition Is Possible

Not all discontinuities can be removed. Redefinition is only possible when the limit exists at the point of discontinuity. This requirement distinguishes removable discontinuities from other types.

Redefinition is appropriate when:

The left-hand and right-hand limits are equal.

The function value is missing or incorrect.

The surrounding graph shows a clear approach to a single y-value.

Redefinition is not appropriate when:

The limit does not exist.

The function is unbounded near the point.

The left-hand and right-hand limits approach different values.

In these cases, redefining the function value would not resolve the underlying issue causing discontinuity.

Conceptual Interpretation

From a conceptual standpoint, removing a hole means making the function’s definition consistent with its behavior. The limit reveals what the function “should” be doing at the point, and redefining the value simply enforces that behavior.

This idea emphasizes an important principle in calculus: continuity is a local property. A function can fail continuity at a single point while behaving smoothly everywhere else, and limits allow us to analyze and correct such isolated issues.

Why Redefinition Matters in Calculus

Redefining function values is more than a technical fix; it supports broader reasoning throughout calculus. Continuous functions are easier to analyze, integrate, differentiate, and apply to real-world contexts.

By using limits to remove holes:

The function becomes mathematically consistent.

The graph reflects the true local behavior.

The function satisfies the formal definition of continuity at the point.

This subsubtopic reinforces the close connection between limits and continuity, highlighting how limits serve not only to describe behavior, but also to refine and improve function definitions when appropriate.

FAQ

A hole typically appears as an open circle on an otherwise smooth segment of the curve, with no jump, vertical break, or oscillation nearby.

If the curve approaches the same height from both sides and only the single point is missing or mismatched, the discontinuity is removable.

A function’s value at a single x-value does not influence its values at any other inputs because continuity is determined locally.

Redefining one point simply patches the missing or incorrect value without changing the algebraic rule governing the rest of the function.

Yes. Removable discontinuities often arise from algebraic expressions that simplify to a form that is continuous everywhere except where the original expression was undefined.

Even complex expressions may hide a hole that becomes visible only after simplification.

Not always. In applied contexts, a hole may represent a genuine physical constraint, such as a forbidden measurement or a missing data point.

Redefining the value is appropriate only when the underlying phenomenon implies that continuity should hold at that point.

If the new value does not match the limit, the discontinuity remains because the function still fails the requirement that its value equal the limiting behaviour.

A mis-assigned value therefore creates a mismatch that is algebraically similar to the original issue, leaving continuity unresolved.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function h is undefined at x = 4. The limit of h(x) as x approaches 4 exists and is equal to 9.

State how h could be redefined at x = 4 to remove the discontinuity.

Question 1

1 mark: States that h(4) should be defined.

1 mark: Correctly states that the value should be 9.

1 mark: Recognises that this redefinition removes the removable discontinuity.

(Max 3 marks; award 1–3 depending on completeness.)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function k is given as follows:

k(x) = (x + 3)(x − 2) for x ≠ 2

k(2) = 15

(a) Determine whether the limit of k(x) as x approaches 2 exists.

(b) State whether the function k is continuous at x = 2.

(c) Explain how k could be redefined to make it continuous at x = 2, referring to the definition of continuity.

Question 2

(a)

1 mark: Correctly identifies that the limit exists.

1 mark: Correctly gives the limit as 5.

(b)

1 mark: States that k is not continuous at x = 2.

(c)

Up to 3 marks:

• Identifies that continuity requires the function value to equal the limit. (1 mark)

• States that k(2) must be redefined to equal 5. (1 mark)

• Explains that doing so satisfies the formal criteria for continuity at a point. (1 mark)

(Max 6 marks overall.)