AP Syllabus focus:

‘Identify discontinuities due to vertical asymptotes, relating them to infinite limits and describing how the function behaves near the asymptote from each side.’

Vertical asymptotes represent locations where a function’s values grow without bound, creating discontinuities characterized by unbounded behavior as the input approaches specific points from either side.

Understanding Discontinuities Caused by Vertical Asymptotes

A vertical asymptote occurs at a value of x = c where a function’s output increases or decreases without bound as the input approaches that value. This produces a specific type of discontinuity in which the function cannot be defined or behave finitely at the point. In AP Calculus AB, these discontinuities are deeply connected to infinite limits, which describe how the function behaves as its output grows arbitrarily large in the positive or negative direction near the asymptote.

When studying vertical asymptotes, it is essential to understand that they arise from the behavior of the function near the value, not necessarily from the function's definedness at that point. Many rational functions, logarithmic expressions, and other formulations exhibit this behavior because their denominators approach zero or their inputs approach restricted values.

Infinite Limits and Unbounded Behavior

When a function approaches a vertical asymptote, the corresponding infinite limit captures how the function behaves near the discontinuity.

Infinite Limit: A limit in which f(x) increases or decreases without bound as x approaches a specific value c.

lim(x → c) f(x) = ∞

f(x) = function value approaching arbitrarily large positive magnitude

c = input value being approached

One-Sided Infinite Limits and Their Importance

A vertical asymptote can often be fully understood only by examining one-sided limits, since the behavior as x approaches the asymptote from the left may differ from the behavior from the right.

One-Sided Limit: A limit where x approaches a value c from only the left (x → c−) or only the right (x → c+).

One-sided infinite limits help describe the direction in which the function diverges on each side of the asymptote. A function might increase without bound on one side and decrease without bound on the other, emphasizing why vertical asymptotes often create dramatic graphical features.

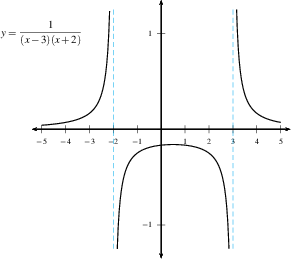

Graph illustrating different one-sided infinite behaviors on either side of two vertical asymptotes, showing how the function diverges to positive or negative infinity. Source.

How Vertical Asymptotes Create Discontinuities

Discontinuities caused by vertical asymptotes arise because the function fails to satisfy the conditions for continuity at the point. For a function to be continuous at x = c, its limit must exist and equal the function’s value there. With vertical asymptotes:

The limit does not exist as a finite number, because the function grows without bound.

The function often cannot be defined at the asymptote, such as when a denominator becomes zero.

Even if the function could be assigned a value at the point, the infinite limit behavior would still break continuity.

Identifying Vertical Asymptotes

To detect vertical asymptotes in expressions, graphs, or contextual descriptions, examine the behavior of the function near values where it becomes undefined or unbounded.

Common Indicators

Denominator approaching zero while the numerator remains nonzero in a rational function.

Logarithmic expressions where the argument approaches zero or becomes negative.

Piecewise definitions where a function’s value near a boundary grows without bound.

Rapid divergence in plotted points or table values as x approaches a particular number.

Describing Behavior Near the Asymptote

When analyzing a function near its vertical asymptote, focus on how the y-values behave:

Do they increase without bound (→ ∞)?

Do they decrease without bound (→ −∞)?

Do the two sides exhibit different behaviors?

Organizing your observations in terms of one-sided limits helps produce precise and mathematically accurate descriptions.

Graphical Interpretation

On a graph, a vertical asymptote appears as a vertical dashed line where the curve grows steeply upward or downward without crossing the line.

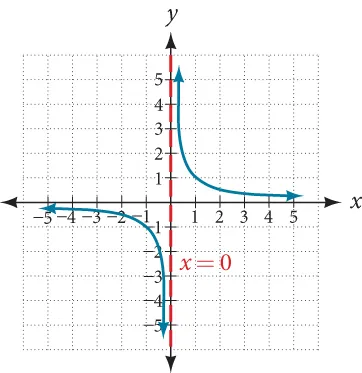

Graph of f(x) = 1/x demonstrating a vertical asymptote at x = 0, with the curve diverging in opposite directions on either side of the asymptote. Source.

Recognizing this structure reinforces understanding of the function’s unbounded behavior and highlights why the asymptote corresponds to a discontinuity.

Why Vertical Asymptotes Matter in AP Calculus AB

Understanding vertical asymptotes strengthens your ability to interpret limiting behavior, recognize discontinuities, and connect algebraic behavior to graphs. These skills support later concepts such as analyzing rational functions, determining integrability, and understanding domain constraints in more advanced calculus settings.

FAQ

A vertical asymptote is uniquely identified by unbounded behaviour: the function values increase or decrease without limit as x approaches a specific value. Other discontinuities, such as removable or jump discontinuities, involve finite values on either side and do not display this divergence.

Vertical asymptotes also demand examination of one-sided limits, as the behaviour can differ dramatically on each side of the asymptote.

No. A function cannot cross a vertical asymptote because the asymptote marks a value of x where the function does not exist and where its values diverge infinitely.

Graphs may appear to cross due to scaling issues, but when examined precisely, the asymptote is always a boundary the function approaches but never reaches.

Vertical asymptotes occur when the denominator equals zero and the numerator does not cancel the factor responsible for that zero.

A rational function may have:

• multiple distinct denominator zeros, each producing an asymptote

• no vertical asymptotes if all such zeros cancel with factors in the numerator

• only one asymptote if there is a single non-cancelled zero

Tables can show rapid growth or decline near a suspected asymptote, revealing patterns a graph’s scale might obscure.

Look for:

• values increasing or decreasing without bound as x approaches a specific number

• asymmetry in behaviour when approaching from the left versus the right

Such numerical evidence helps verify unbounded tendencies even when a graph appears smooth or hides steep changes.

Yes. A function may be defined at the point of a vertical asymptote, though the definition does not affect the asymptotic behaviour.

For example, a piecewise function may assign a specific value at x = c, but if nearby values of the function diverge infinitely, the asymptote still exists. The point’s definition does not restore continuity or remove the infinite discontinuity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The function g is defined for all real x except x = 4. The graph of g shows that as x approaches 4 from the left, g(x) decreases without bound, and as x approaches 4 from the right, g(x) increases without bound.

a) State the type of discontinuity at x = 4. (1 mark)

b) Explain briefly why this discontinuity occurs. (1–2 marks)

Question 1

a) 1 mark: Correctly identifies the discontinuity as a vertical asymptote (or infinite discontinuity).

b) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that the function values grow without bound as x approaches 4.

• 1 mark for linking this behaviour to an infinite limit or unbounded behaviour on each side of x = 4.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function f(x) = (3x + 1) / (x − 2).

a) Determine the value of x at which f has a vertical asymptote. (1 mark)

b) Evaluate the one-sided behaviour of f(x) as x approaches 2 from the left. (1–2 marks)

c) Evaluate the one-sided behaviour of f(x) as x approaches 2 from the right. (1–2 marks)

d) Using your answers above, explain why f is discontinuous at x = 2. (1 mark)

Question 2

a) 1 mark: Correctly states x = 2 because this value makes the denominator zero.

b) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that as x approaches 2 from the left, the denominator is negative and small in magnitude.

• 1 mark for concluding f(x) tends to negative infinity.

c) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that as x approaches 2 from the right, the denominator is positive and small in magnitude.

• 1 mark for concluding f(x) tends to positive infinity.

d) 1 mark: Correctly states that the function is discontinuous at x = 2 because the limit does not exist as a finite value and instead diverges to infinity.