AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use algebraic techniques such as multiplying by a conjugate to simplify expressions involving radicals, producing equivalent forms that reveal finite limit values.’

Rationalizing expressions in limit problems helps transform indeterminate radical forms into simpler, equivalent expressions that allow direct evaluation of a function’s behavior near a point.

Understanding the Purpose of Rationalizing in Limits

Rationalizing is a targeted algebraic strategy used when limits involve radical expressions that prevent direct substitution. These cases frequently produce indeterminate forms, particularly , because subtracting or combining radicals often masks a stable value that the limit approaches. Rationalizing rewrites the expression into an equivalent form that reveals the hidden behavior of the function and makes the limit accessible using standard limit laws.

Indeterminate Forms and Radicals

When substitution yields an indeterminate form, the structure of the expression—not the limit itself—is the source of difficulty. Radicals, especially in differences like , introduce non-linear behavior that obscures cancellation. Rationalizing eliminates these obstructions by creating algebraic expressions free of problematic radicals in the numerator or denominator.

The Conjugate as a Rationalizing Tool

The most common method for simplifying radical expressions in limits is multiplying by a conjugate, introduced here as a central technique.

Conjugate: For an expression of the form , where one of the terms contains a radical, the conjugate is , and vice versa.

Multiplying by a conjugate leverages the identity to remove radicals and simplify the structure of a limit. This produces a new form that is algebraically equivalent everywhere except possibly at the point causing the indeterminate form. Because limits focus on nearby values rather than the exact point, this equivalence maintains the limit while enabling simplification.

After the definition above, it is important to note that the conjugate method applies not only to binomial radicals but also to more complex expressions whenever the structure fits the difference-of-squares pattern.

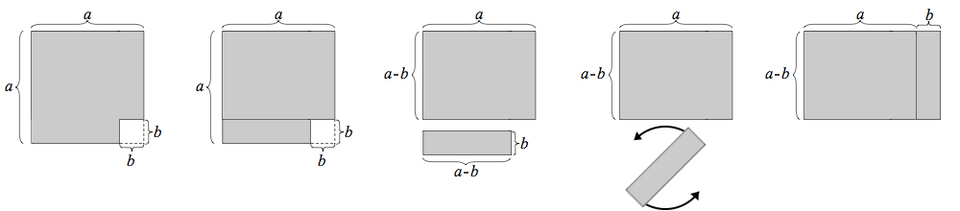

Multiplying by the conjugate relies on the difference of squares identity, which turns a product of binomials with radicals into an expression without radicals.

Geometric illustration of the identity , showing how the difference of squares structure enables cancellation when multiplying by conjugates in rationalization. Source.

When and Why Rationalizing Works

Rationalizing is appropriate when:

The limit involves radical expressions whose substitution leads to .

A difference of radicals appears in either the numerator or denominator.

Standard limit laws cannot be applied until an algebraic obstruction is removed.

The simplified form reveals a continuous expression near the limiting value.

Rationalizing works because it transforms nonlinear radical components into polynomial or rational components that are easier to analyze using continuity and substitution. By eliminating radicals in key positions, the function often becomes continuous at the point of interest, allowing direct evaluation of the limit.

Rationalizing the Numerator

A frequent situation occurs when the numerator contains a difference of radicals. Multiplying numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the numerator:

Removes radicals from the numerator.

Creates a difference of squares that simplifies to non-radical terms.

Allows factors causing the indeterminate form to cancel, exposing a manageable expression.

This procedure preserves the value of the limit because multiplying by a conjugate over itself is equivalent to multiplying by 1. Students should remember that the conjugate must match the structure of the radical expression exactly for the identity to apply successfully.

Rationalizing the Denominator

Some limits require rationalizing the denominator instead, particularly when the denominator’s radical prevents evaluation through direct substitution. Multiplying by the conjugate of the denominator:

Ensures that the denominator becomes a rational expression.

Transfers any remaining radicals to the numerator in a controlled form.

Helps identify cancellations or simplifications needed for evaluating the limit.

This technique follows the same algebraic principles but focuses on ensuring that the denominator does not approach zero in a way that obscures the limit.

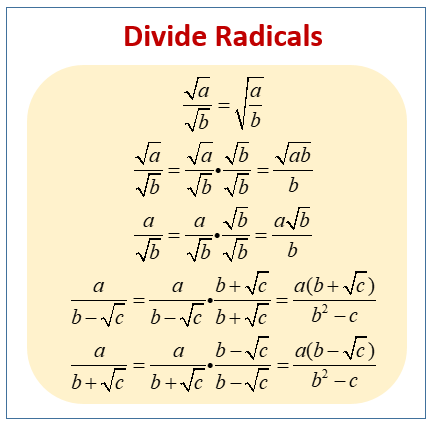

When the radical appears in a denominator, rationalizing by multiplying numerator and denominator by an appropriate radical or conjugate produces an equivalent expression with a rational denominator.

Diagram summarizing key rules for dividing and simplifying radical expressions, including rationalizing denominators with conjugates. It reinforces the algebraic operations used to prepare radical expressions for limit evaluation. Source.

Equivalent Forms and their Importance in Limits

The syllabus emphasizes producing equivalent forms because the purpose of rationalization is not to alter the behavior of the function but to reveal it. Equivalent forms maintain:

Identical function values for all except possibly the limiting point.

The same limit as the original expression.

A clearer path to applying limit laws and substitution.

Rationalizing is one method among many for generating such equivalent expressions, but it is uniquely suited to radical contexts where direct cancellation is otherwise impossible.

Structure of Equivalent Expressions

A successful rationalization typically yields:

A simplified numerator free of radicals interfering with cancellation.

A denominator no longer equal to zero after cancellation.

A final expression that is continuous at the limit point, meaning substitution is now valid.

Using Rationalizing Strategically

Rationalizing should be viewed as a strategic tool rather than a universal requirement. Students should consider it when:

The structure of the expression includes radicals resisting direct substitution.

Factoring does not resolve the indeterminate form.

The goal is to reveal a finite limit obscured by algebraic complexity.

These decisions align with the broader AP Calculus AB expectation that students select approaches appropriate to the form of a limit problem.

Rationalization in Broader Limit Contexts

Because rationalization creates equivalent expressions, it connects directly to previous limit techniques such as continuity, factored cancellations, and limit laws. It exemplifies the general method of transforming a problematic expression into a tractable one without changing the underlying limit, reinforcing the importance of algebraic manipulation in limit evaluation.

FAQ

Multiplying by the conjugate changes the algebraic appearance of the expression but not its behaviour near the limiting value. This is because the conjugate is introduced as part of a factor equal to 1, so the transformation preserves equivalence for all x-values except possibly the point where the limit is taken.

The limit concerns values arbitrarily close to that point, not the value at the point itself, so the simplification remains valid for evaluating the limit.

Rationalising is particularly efficient when:

• You see a difference of radicals such as sqrt(x + a) − sqrt(x).

• Substitution yields a zero-over-zero form and the radicals prevent obvious cancellation.

• Factoring does not produce a usable cancellation structure.

A good rule of thumb is: if radicals create the barrier, use the conjugate.

You must use the full conjugate of the entire binomial containing the radical. For example, the conjugate of 3 − sqrt(x + 1) is 3 + sqrt(x + 1), not merely sqrt(x + 1).

Using a partial conjugate will not generate the difference-of-squares outcome required to remove the radical, meaning the simplification will fail to resolve the indeterminate form.

After rationalising, factors that previously caused a zero-over-zero form frequently cancel, leaving an expression defined and continuous in a neighbourhood of the limiting point.

Once continuity is restored, direct substitution becomes valid, allowing the limit to be evaluated using the simplified expression rather than the original one.

Rationalising may remove radicals but it does not change domain restrictions that already existed; cancelled factors still indicate points where the original expression was undefined.

However, the simplified form can sometimes appear valid at the limiting point even though the original expression was undefined there. This is acceptable because limits concern nearby values, but the point itself must not be treated as belonging to the domain unless explicitly redefined.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Evaluate the limit by rationalising the expression:

lim (x → 4) [ (sqrt(x) − 2) / (x − 4) ].

Show all algebraic steps leading to your answer.

Question 1

• Correct rationalising step: multiply numerator and denominator by (sqrt(x) + 2). (1 mark)

• Correct simplification to obtain (sqrt(x) − 2)(sqrt(x) + 2) in the numerator and x − 4 in the denominator. (1 mark)

• Correct final limit value: 1/4. (1 mark)

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function f defined for x ≠ 9 by

f(x) = (3 − sqrt(x)) / (9 − x).

(a) Rationalise the numerator and simplify f(x) into an equivalent form valid for x ≠ 9.

(b) Hence determine lim (x → 9) f(x).

(c) State whether the limit suggests a removable discontinuity at x = 9, giving a brief reason.

Question 2

(a)

• Multiply top and bottom by the conjugate (3 + sqrt(x)) to rationalise the numerator. (1 mark)

• Correct simplification of numerator to 9 − x. (1 mark)

• Correct cancellation leading to f(x) = 1 / (3 + sqrt(x)). (1 mark)

(b)

• Correct substitution of x = 9 into the simplified expression. (1 mark)

• Correct limit value: 1 / 6. (1 mark)

(c)

• Correct statement that the discontinuity at x = 9 is removable, with justification (the limit exists and is finite, while the original expression is undefined at x = 9). (1 mark)

Total: 6 marks