AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize when rewriting a function into an equivalent form, or applying identities, makes a limit easier to evaluate using previous limit laws or other theorems.’

Strategically rewriting expressions helps reveal hidden behavior in limits. By creating equivalent forms, students overcome indeterminate structures and apply established limit laws with clarity and precision.

Strategic Use of Algebraic Rearrangement

When evaluating limits, the ability to rewrite a function into an equivalent form is essential for removing obstacles such as indeterminate expressions, hidden factors, or inaccessible limit laws. This subsubtopic emphasizes recognizing when an expression’s current form obscures a limit and determining which algebraic techniques clarify the function’s behavior near the point of interest.

When Rearrangement Is Necessary

Students often encounter expressions where direct substitution fails or produces an indeterminate form like . Rearrangement allows the underlying structure to become visible. Key motivations for rewriting include:

Exposing common factors that can be canceled legally.

Transforming radical expressions to eliminate irrational components.

Using algebraic identities that simplify trigonometric or polynomial expressions.

Revealing continuity properties that permit the application of limit laws.

Isolating terms to which known theorems, such as the Squeeze Theorem, can be applied.

Identifying Equivalent Forms

An equivalent form of a function is a mathematically identical expression defined on all points where both forms are valid. Equivalent forms are not approximations; they preserve the function’s behavior on its domain, excluding points made undefined by temporary manipulations.

Equivalent Form: A rewritten version of an expression that produces the same output values as the original expression for all in the shared domain.

Recognizing equivalence is critical because applying limit laws requires access to a function’s values arbitrarily close to the limit point, even when the function is undefined at that point itself.

A sentence here ensures spacing before any later equation material.

Common Algebraic Strategies

Students should choose techniques that align with the structure of the expression being analyzed. Strategic selection prevents unnecessary manipulation and maintains conceptual clarity.

1. Factoring to Reveal Structure

Factoring can uncover multiplicative relationships hidden in expanded expressions. Useful patterns include:

Common factors across terms

Difference of squares

Perfect square trinomials

Polynomial division that exposes a cancellation opportunity

Once factored, expressions may allow term cancellation, transforming a blocked limit into one that can be evaluated using substitution.

2. Rationalizing to Remove Radicals

Rationalizing is especially effective when radicals create indeterminate forms.

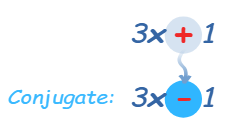

This diagram illustrates the concept of a conjugate by pairing two expressions that differ only in the sign between terms, demonstrating the structure used when rationalizing expressions containing radicals. Source.

Multiplying by a conjugate eliminates the radical through a difference-of-squares identity. This process often converts a complex radical structure into a simpler polynomial form that obeys familiar limit laws.

3. Using Algebraic Identities

Algebraic identities connect different representations of functions. Applying them strategically helps transform an expression into one suitable for direct limit computation. Some identities commonly used include:

Polynomial expansions that isolate terms

Trigonometric identities that relate ratios or squares

Logarithmic and exponential identities used to separate products or powers

These identities improve accessibility and reveal behavior not apparent in the original form.

Applying Limit Laws After Rearrangement

After rewriting an expression, students can apply previously established limit laws to compute the desired value. Rearranged forms should make it clearer when:

The limit is found through direct substitution

One-sided behavior needs evaluation

The resulting expression now aligns with a known continuous function

The limit can be decomposed into sums, differences, products, or quotients

= First function approaching limit

= Second function approaching limit

Because rearranged expressions often clarify continuity or smoothness, they provide a foundation for confidently applying these laws.

A sentence here ensures spacing before any later definition or equation is used.

Strategic Decision-Making

The central skill is knowing when to rearrange a function and which method to use. Effective strategies include:

Identifying whether an expression’s surface structure prevents direct substitution.

Determining whether a hidden factor or cancelable term exists.

Considering whether algebraic or trigonometric identities lead to a more transparent representation.

Checking whether rearrangement allows direct application of continuity or theorems such as the Squeeze Theorem.

These decisions rely on pattern recognition and familiarity with common algebraic forms.

Pitfalls to Avoid

Even correct algebraic techniques can be misapplied if the student does not monitor domain restrictions or equivalence. Important cautions include:

Avoid canceling terms that equal zero at the limit point unless the cancellation is justified for nearby values.

Ensure that multiplying by a conjugate or identity does not change the function’s value except at removable points.

Do not introduce approximations that alter exact behavior required for limit evaluation.

Remember that rewriting for convenience must preserve correctness across all relevant -values.

How This Skill Supports Broader Limit Techniques

Strategic rearrangement is a foundational tool that supports deeper limit topics throughout calculus. It enables students to:

Transform indeterminate expressions into computable ones.

Apply limit laws consistently and rigorously.

Recognize removable discontinuities through algebraic inspection.

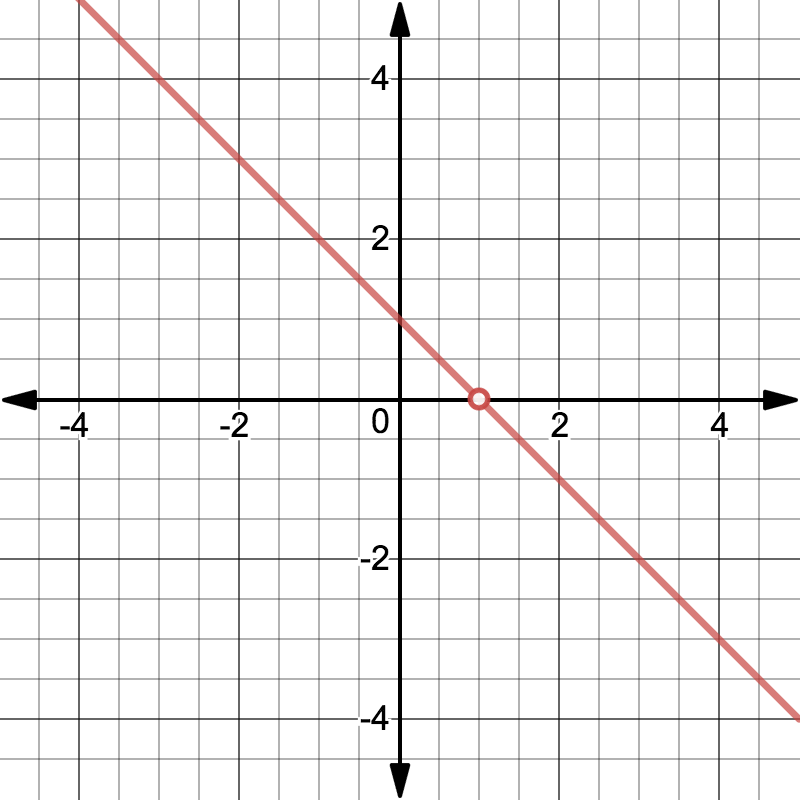

This graph shows a continuous line with a hole at one point, visually representing a removable discontinuity that can be revealed through algebraic simplification such as factoring and canceling. Source.

Prepare expressions for numerical, graphical, or theorem-based approaches.

This subsubtopic reinforces that algebraic creativity, when used with precision, is essential for navigating complex limit structures within AP Calculus AB.

FAQ

Look for structural cues that signal hidden simplifications. These include repeated terms, expressions resembling identities, or radicals paired with sums or differences.

You can also test whether substitution fails because of a removable discontinuity rather than unbounded behaviour. If both numerator and denominator approach zero and no oscillatory pattern appears, rearrangement is often promising.

Yes. Expressions may appear similar but differ on domain restrictions or introduce terms not defined near the limit point.

Be cautious when:

• Manipulations introduce a term that becomes undefined close to the limit.

• An identity is applied incorrectly outside its valid domain.

• Cancelling a factor removes information about one-sided behaviour.

Choose the conjugate of whichever radical term is preventing simplification. The goal is to eliminate the radical that causes an indeterminate expression.

Guidelines:

• If the radical is in the numerator, rationalise the numerator.

• If the radical is in the denominator, rationalise the denominator.

• Pick the version that produces cancellable terms or exposes continuity.

The key issue is forgetting that cancelled factors may represent points where the original function is undefined.

To avoid this:

• Always check whether the cancelled factor equals zero at the limit point.

• Retain awareness of domain restrictions even after simplification.

• Use the simplified form for limit evaluation, not for redefining the original function.

Rearrangement can ensure that each piece takes a form that reveals its behaviour near the boundary, making comparison of side limits more transparent.

Useful approaches include:

• Factoring polynomials within pieces to show whether cancellations occur.

• Using identities to match expressions on both sides of a boundary.

• Simplifying each piece independently to isolate the value approached from each side.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The function f is defined for all x not equal to 2 by

f(x) = (x² − 4) / (x − 2).

(a) Rewrite f(x) into an equivalent form that can be evaluated at x = 2.

(b) Hence determine the limit of f(x) as x approaches 2.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: Correctly factorises the numerator as (x − 2)(x + 2).

1 mark: Cancels the common factor to obtain the equivalent form f(x) = x + 2.

(b) 1 mark: Evaluates limit as x approaches 2 to obtain 4.

Total: 2–3 marks depending on working shown.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function

g(x) = (sqrt(9 + x) − 3) / x, for x not equal to 0.

(a) Explain why direct substitution cannot be used to evaluate the limit of g(x) as x approaches 0.

(b) Use an appropriate algebraic rearrangement to rewrite g(x) into an equivalent form suitable for evaluating the limit.

(c) Hence determine the limit as x approaches 0.

(d) Briefly justify why the rewritten expression is equivalent to g(x) for values of x near 0.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark: States that substitution gives 0/0 or an indeterminate form, preventing direct evaluation.

(b) 1–2 marks: Multiplies numerator and denominator by the conjugate (sqrt(9 + x) + 3) and simplifies correctly to obtain 1 / (sqrt(9 + x) + 3).

(c) 1 mark: Correctly evaluates the limit as 1/6.

(d) 1 mark: Explains that multiplying by the conjugate introduces no change in value for x not equal to 0, so the forms are equivalent for all x near 0.

Total: 4–6 marks depending on accuracy and clarity.