AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rearrange expressions by factoring and cancelling common factors to create equivalent forms that allow direct evaluation of limits that originally produced indeterminate forms.’

Factoring and cancelling common factors simplifies expressions that initially yield indeterminate forms, allowing limits to be evaluated through clearer algebraic structure and predictable function behavior near a point.

Understanding the Role of Factoring in Limit Evaluation

When a direct substitution into a limit produces an indeterminate form such as , algebraic manipulation becomes essential. Factoring exposes the internal structure of an expression so that unnecessary complexity can be removed. Once simplified, the function often becomes easier to analyze near the point of interest, permitting evaluation using standard limit laws.

Indeterminate Forms and the Need for Algebraic Restructuring

An indeterminate form is an expression whose value cannot be determined directly from substitution because the symbolic outcome gives no information about the limit’s true behavior.

Indeterminate Form: An expression such as that does not reveal the actual limit value and requires additional algebraic or analytic techniques.

Factoring targets the algebraic source of the indeterminacy by revealing shared factors in numerator and denominator that can be cancelled when the cancellation does not violate domain restrictions.

Factoring Techniques Relevant to Limit Problems

The most common factorable structures arise when functions involve polynomial terms that vanish at the same input value.

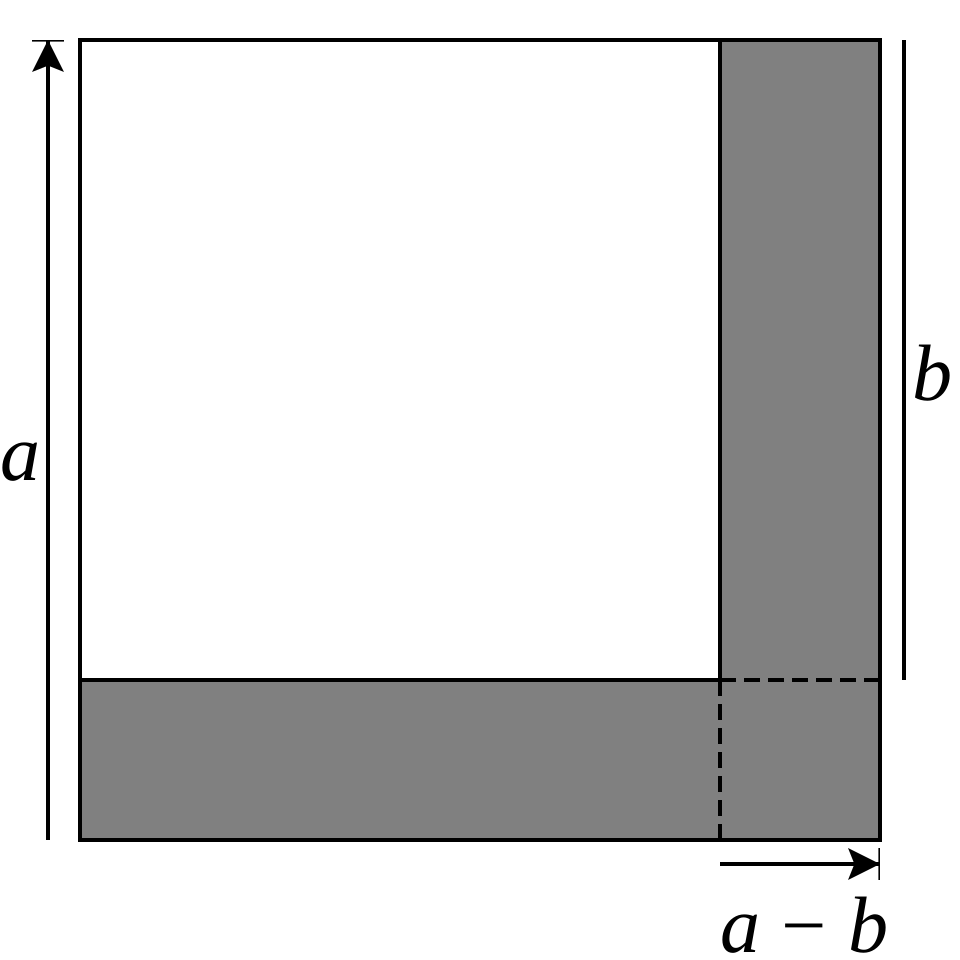

A geometric illustration of the difference of squares identity, representing as a large square minus a smaller square. The L-shaped region visually reveals how the expression factors into , supporting its use in simplifying algebraic limit expressions. Source.

Common Polynomial Factoring Patterns

Students frequently encounter the following patterns when simplifying limits:

Common monomial factors, where each term shares a numerical or variable factor.

Quadratic factoring, including trinomials that split into two binomials.

Difference of squares, rewriting an expression of the form into .

Perfect square trinomials, recognizable by symmetric structure around a middle term.

Higher-degree polynomials, which may contain repeated factors essential to cancellation.

These patterns help create equivalent expressions that better expose cancelable components.

Equivalent Forms and Domain Considerations

An equivalent form is one that matches another expression in value for all in the domain where both are defined. In limits, equivalence excludes the specific input value that causes the indeterminate form, since the limit concerns behavior near, not at, the point.

Equivalent Form: An expression that produces identical output values to another expression for all where both are defined, even if values differ at isolated points.

Once an equivalent form is obtained, standard limit laws allow direct substitution, as long as the resulting expression is defined.

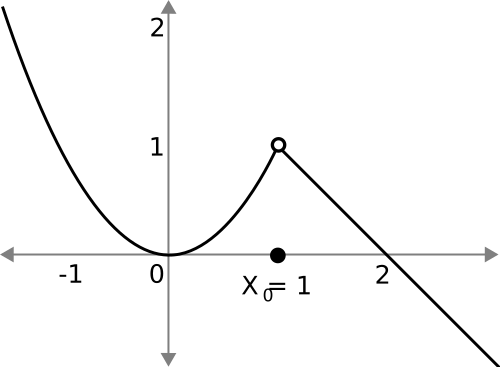

A graph illustrating a removable discontinuity, where the function is undefined at a single point but approaches the same value from both sides. The open circle marks the hole, emphasizing that the limit depends on nearby behavior rather than the function’s value at that point. Source.

Cancelling Common Factors in Limit Problems

Cancellation is permissible only when the factor being cancelled is nonzero in the region where the limit is taken. Even though the problematic point itself may make the factor zero, the limit examines values arbitrarily close to that point.

Why Cancellation Does Not Change the Limit

Because limits involve approaching a value rather than evaluating the function exactly at that value, removing a factor that is zero only at the limiting point does not alter nearby behavior. The resulting simplified expression is therefore valid for computing the limit.

= Limit of simplified expression after cancelling a nonzero common factor near

= Numerator function

= Denominator function

= Input value approached

This principle applies broadly to rational expressions, polynomial structures, and functions containing embedded factors.

Systematic Process for Factoring and Cancelling in Limits

A structured approach increases accuracy and helps avoid algebraic missteps.

Step-by-Step Reasoning Framework

Check substitution first to verify whether an indeterminate form such as appears.

Identify common algebraic structure in the numerator and denominator, searching for factorizable components.

Factor completely, ensuring all polynomial factors or special patterns are isolated.

Cancel only those factors that remain nonzero for values near the target point.

Rewrite the simplified expression and apply direct substitution using continuity principles.

Interpret the resulting value as the limit, understanding that the simplified expression need not agree with the original at the limiting point itself.

This method aligns with the syllabus requirement to use algebraic restructuring to resolve indeterminate forms and compute limits directly.

Importance of Full Factorization

Only full factorization guarantees exposure of all potentially cancelable components. Partial factorization may leave hidden complexity that prevents simplification and obscures limit behavior. Ensuring completeness prevents algebraic errors and supports conceptually accurate limit computation.

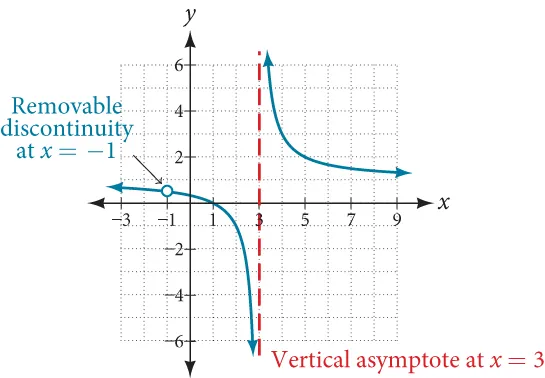

A rational function displaying a removable discontinuity at and a vertical asymptote at . The open circle illustrates how a canceled factor creates a hole where the original function was undefined, while the asymptote highlights the contrasting behavior of non-cancelable factors. Source.

FAQ

Factoring exposes algebraic structure that numerical estimation cannot reveal. Indeterminate forms arise from expressions disguising their true limiting behaviour, and factoring removes the source of that disguise.

Numerical methods may suggest a limit but cannot justify it. Factoring, however, produces an equivalent expression that explicitly shows how the limit emerges once the problematic factor is cancelled.

A factor may be cancelled only if it is non-zero for all values near the point of interest, even if it equals zero at the point itself.

To verify this:

• Check whether the factor is zero only at the limiting value.

• Ensure the cancellation does not change the function on any interval around that point.

If both conditions hold, cancelling the factor preserves the limit.

A cancelled factor vanishes only at the point where the indeterminate form occurs. Everywhere else, the original and simplified expressions have identical algebraic values.

Graphically, the only difference is that the original function has a hole at that point, while the simplified expression draws the curve through that hole, matching the limiting behaviour.

Yes. Even when standard patterns are not immediately visible, systematic techniques can reveal hidden structure.

Useful strategies include:

• Grouping terms to create factorable pairs.

• Searching for repeated linear factors through synthetic or polynomial division.

• Identifying whether the polynomial equals zero at the limiting value and thus must contain a corresponding factor.

Students frequently cancel too early or cancel terms that are not genuine factors.

Errors include:

• Cancelling terms within sums rather than factors within products.

• Ignoring domain restrictions and assuming the simplified expression equals the original everywhere.

• Overlooking that cancellation removes only a hole, not discontinuities caused by non-cancelable denominator factors.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The function f is defined by

f(x) = (x² - 9) / (x - 3).

(a) State why direct substitution of x = 3 gives an indeterminate form.

(b) Hence determine the limit of f(x) as x approaches 3.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: States that substitution gives 0/0 or an indeterminate form.

(b) 1 mark: Factors x² - 9 as (x - 3)(x + 3).

1 mark: Cancels the common factor and evaluates the resulting expression to give 6.

Total: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function

g(x) = (x² + 4x + 3) / (x + 1).

(a) Factor the numerator fully.

(b) Explain why the function g has a removable discontinuity.

(c) Determine the exact value of the limit of g(x) as x approaches -1.

(d) State the value that could be assigned to g(-1) to make g continuous at x = -1.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark: Correct factorisation of x² + 4x + 3 as (x + 1)(x + 3).

(b) 1 mark: States that g has a removable discontinuity because a factor cancels, leaving a hole at x = -1.

(c) 1 mark: Cancels the factor (x + 1).

1 mark: Correctly evaluates the simplified expression x + 3 at x = -1 to obtain 2.

(d) 1 mark: States that g(-1) should be defined as 2 to make the function continuous.

Total: 5 marks.