AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use the squeeze theorem to justify important trigonometric limits, such as the limits of sin(x)/x and (1 − cos(x))/x as x approaches zero.’

Understanding how trigonometric functions behave near zero is essential in calculus, and the squeeze theorem provides a powerful method for establishing foundational limit results used throughout differentiation.

Key Idea of Applying the Squeeze Theorem to Trigonometric Limits

The squeeze theorem becomes especially valuable when a function’s value cannot be determined by direct substitution, yet its behavior is bounded by two simpler functions whose limits are known. Trigonometric expressions near zero often exhibit this property, making them ideal candidates for this technique.

Why Trigonometric Limits Require Squeezing

Direct substitution in expressions like or at leads to indeterminate forms, which provide no immediate information about the function's limiting behavior. The squeeze theorem helps resolve this by comparing the target function to bounding functions that behave more predictably.

Understanding the Structure of Trigonometric Behavior Near Zero

Key trigonometric functions change smoothly near zero, but their ratios can produce undefined values or ambiguous numerical behavior. To address this, the squeeze theorem uses geometric or algebraic bounds to constrain the function’s value as approaches zero. This approach links the subtle behavior of trigonometric expressions to limits that are essential for defining derivatives of trigonometric functions.

The Foundational Trigonometric Limit:

This limit plays a central role in differential calculus because it directly supports the derivative of .

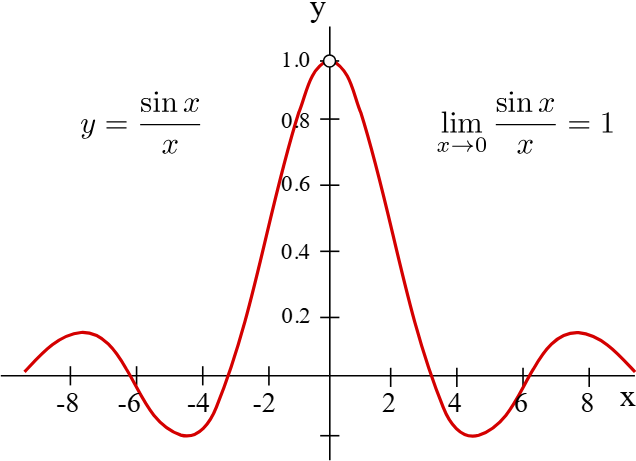

The graph shows how sin(x)/x\sin(x)/xsin(x)/x approaches 1 as xxx approaches zero, emphasizing that the limit exists even though the function is undefined at the origin. Source.

Squeeze Theorem: If near a point , and , then .

In the context of , a classical geometric inequality shows that for near zero (and measured in radians):

.

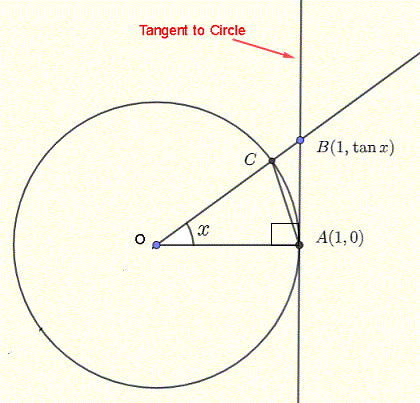

The diagram illustrates how comparing areas of a triangle, sector, and tangent-formed triangle leads to the inequalities needed to squeeze sin(x)/x\sin(x)/xsin(x)/x between cosx\cos xcosx and 1. Source.

Both bounding functions approach as , allowing the squeeze theorem to confirm that the middle expression approaches the same value.

A necessary sentence here ensures spacing before the next equation block.

= angle measure in radians

= sine function value corresponding to angle

This establishes one of the most important trigonometric limits in calculus and forms the basis for evaluating other related limits.

Applying Squeezing to

A second essential trigonometric limit arises in the study of derivatives for cosine. The expression cannot be evaluated using direct substitution, and recognizing its behavior requires bounding techniques related to the previous limit.

Why This Expression Needs Special Handling

As with the previous ratio, substituting into produces division by zero. However, unlike the ratio, this expression approaches zero rather than a nonzero constant, and its analysis benefits from manipulating trigonometric identities in conjunction with squeezing.

Trigonometric Identity: A relationship, true for all permissible values of the variable, connecting trigonometric functions such as and .

By rewriting using the Pythagorean identity or related transformations, the expression becomes easier to compare to known bounded forms. These rewritten forms, together with knowledge of how behaves near zero, allow the construction of bounds to apply the squeeze theorem effectively.

A bridging sentence is included here to separate the definition from the equation block.

= angle measure in radians

= cosine function value corresponding to angle \cos(x)\sin(x)\cos(x)x$ approaches zero.

Check the domain and angle units. These trigonometric limits rely on angle measure in radians; using degrees would invalidate the relationships necessary for squeezing.

Importance of These Limits in Calculus

The trigonometric limits justified using the squeeze theorem support foundational derivative rules and appear throughout the study of differential equations, series, and modeling situations involving periodic motion. These results ensure that trigonometric functions behave predictably near zero and provide a rigorous starting point for deeper calculus concepts.

FAQ

Radians ensure that the arc length on the unit circle equals the angle measure itself. This property is essential for deriving the geometric inequalities used to squeeze sin(x)/x.

In degrees, the proportional relationship between arc length and angle does not hold, so the inequalities fail and the limit no longer evaluates to the correct value.

The same inequality structure applies because the geometry of the unit circle is symmetric about the x-axis. The signs of the trigonometric expressions reflect across the axis, but the bounding behaviour remains unchanged.

Thus, sin(x)/x approaches 1 from both sides, ensuring the limit is unaffected by the direction of approach.

Yes, provided suitable bounding functions can be found. This often involves rewriting expressions into forms involving sin(x) or cos(x) near zero.

For example, limits involving tan(x), sin(ax), or cos(ax) may be squeezed once identities or inequalities reduce them to known behaviours.

Near zero, sin(x) is approximately linear, while 1 − cos(x) grows quadratically. This difference explains why sin(x)/x approaches a non-zero constant, but (1 − cos(x))/x approaches zero.

This contrast arises from the shapes of the sine and cosine graphs, where cosine has a turning point at zero but sine crosses the axis with non-zero slope.

No. Alternatives include power series expansions or defining sine and cosine through differential equations. However, these approaches require mathematical structures beyond the AP curriculum.

The geometric squeeze method remains the most accessible and aligns cleanly with the foundational goals of introductory calculus.

Practice Questions

A function f is defined for values of x close to 0 by f(x) = sin(x) / x.

(a) Use the Squeeze Theorem to determine the limit of f(x) as x approaches 0.

[1–3 marks]

(a)

• States or uses the inequalities cos(x) ≤ sin(x) / x ≤ 1 for x near 0. (1 mark)

• States that both bounding functions approach 1 as x approaches 0. (1 mark)

• Concludes that the limit is 1 by the Squeeze Theorem. (1 mark)

Consider the function g(x) = (1 − cos(x)) / x for x not equal to 0, and g(0) = k.

(a) Use an appropriate trigonometric identity to rewrite g(x) in a form suitable for applying the Squeeze Theorem.

(b) Determine the limit of g(x) as x approaches 0.

(c) Find the value of k that makes g continuous at x = 0.

[4–6 marks]

(a)

• Correctly rewrites 1 − cos(x) as 2 sin²(x/2). (1 mark)

• Expresses g(x) in the form 2 sin²(x/2) / x or equivalent. (1 mark)

(b)

• Uses the identity sin(x/2) / (x/2) approaches 1 as x approaches 0, or an equivalent squeeze argument. (1 mark)

• Concludes that the limit of g(x) as x approaches 0 is 0. (1 mark)

(c)

• States that continuity requires g(0) = limit as x approaches 0 of g(x). (1 mark)

• Concludes that k must be 0. (1 mark)