AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain the squeeze theorem, which uses two functions that bound a third function and share the same limit at a point to determine the limit of the middle function.’

This section develops the core idea behind the Squeeze Theorem, showing how bounding functions and shared limits reveal hidden behavior of functions approaching a point.

Understanding the Purpose of the Squeeze Theorem

The Squeeze Theorem helps determine limits of functions whose behavior is difficult to compute directly. It formalizes the intuitive idea that if a function is “trapped” between two other functions that both approach the same limit, then it must approach that limit as well. This makes the theorem a central tool in early limit theory, especially for functions that oscillate, behave irregularly, or do not simplify easily using algebraic methods.

The theorem is particularly meaningful when average approaches fail or when direct substitution produces an indeterminate form. It provides a reliable approach whenever bounding relationships can be established. Because AP Calculus AB students often encounter limits involving trigonometric expressions or functions defined implicitly, the Squeeze Theorem becomes essential for building conceptual understanding of limit behavior.

Statement of the Squeeze Theorem

Before introducing the formal statement, it is important to understand the role of bounding in limit analysis. A function is bounded near a number if it stays within a specific numerical range, regardless of whether the function approaches the value smoothly.

Bounding Functions: Functions that provide upper and lower constraints on another function’s values within a specified interval near a point.

The Squeeze Theorem uses bounding functions to “pin down” the limit of a third function when the third function’s behavior is otherwise hard to compute.

= Functions defined near

= Point approached

= Common limit value

This formal structure ensures that the behavior of is determined entirely by the behavior of and near the specified point.

The Squeeze Theorem uses bounding functions to “pin down” the limit of a third function when the third function’s behavior is otherwise hard to compute.

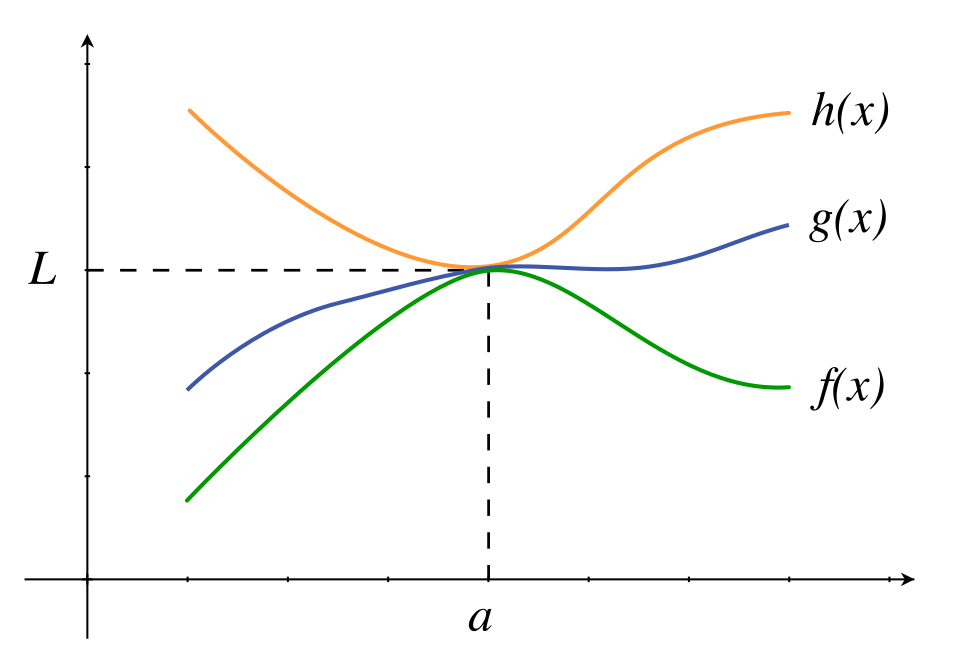

A graph of three functions illustrating the Squeeze Theorem, showing the middle function trapped between two bounding functions that share a common limit L at x = a. Source.

Intuition Behind the Theorem

The intuitive concept is straightforward: if a function cannot escape the “trap” formed by two other functions that tighten toward the same limit, then the trapped function must settle at that limit as well. This reflects a fundamental idea in calculus that limit values depend on nearby behavior rather than the function’s value at the point itself.

The intuition can be understood through three key ideas:

Convergence Pressure

As x approaches a point, if the bounding functions move closer together and converge to the same limit, they create a narrowing corridor that forces the middle function to follow.

Local Behavior Dominance

The Squeeze Theorem does not require the inequalities to hold everywhere; they must hold only in a neighborhood around the point of interest. This emphasizes that limits depend on local behavior.

Independence from Function Value

The actual values of f(x) at the point c—or even whether f(c) exists—are irrelevant to the theorem. Only the surrounding values matter for determining the limit.

Conditions Required for the Squeeze Theorem

For the theorem to apply correctly, three conditions must be met. These conditions are essential for AP Calculus AB students to recognize, especially when determining whether the method is appropriate for a given limit problem.

1. A Valid Bounding Relationship

To use the theorem, the inequalities must hold for all x sufficiently close to c (but not necessarily at c).

Important characteristics include:

The middle function must remain between the two bounding functions.

The inequalities can be strict or non-strict.

The bounds do not need to hold at the point c itself.

2. A Common Limit for the Bounding Functions

Both bounding functions must approach the same limit as x approaches c.

Key ideas:

This limit must exist and be finite.

If either bounding function lacks a limit or approaches different values, the theorem cannot conclude anything about the middle function.

3. Proximity of the Bound Functions Near the Target Point

The bounding functions do not have to be close to each other for all x—only near c.

This reinforces the principle that limit behavior focuses strictly on values arbitrarily close to the point.

Why the Squeeze Theorem Is Useful

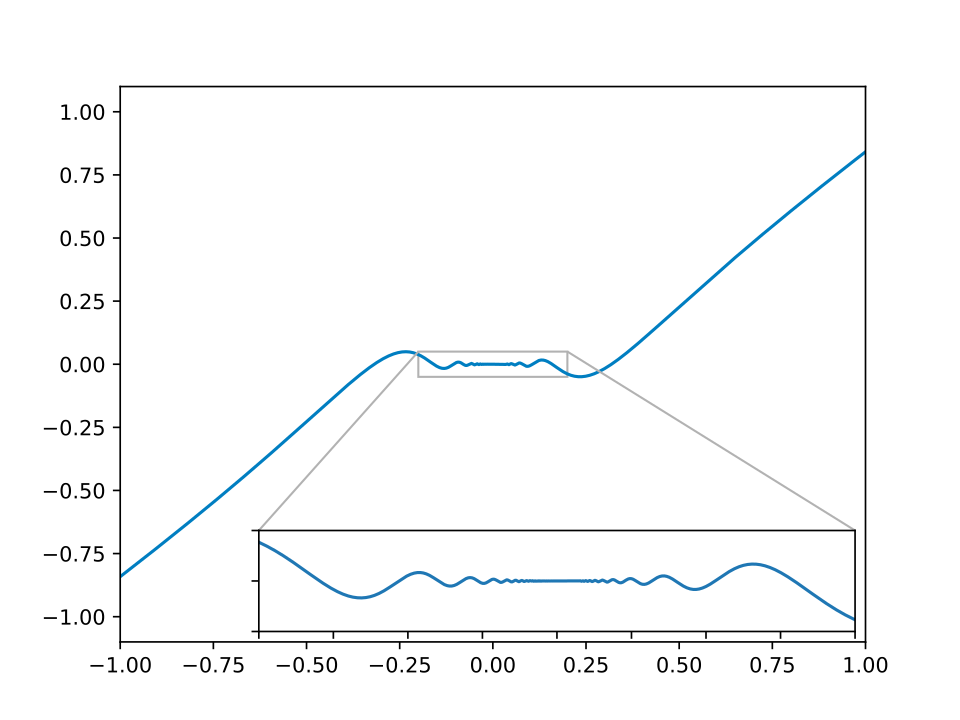

The theorem becomes an essential strategy when algebraic manipulation is insufficient or impossible. It is especially powerful in dealing with functions that oscillate yet remain bounded within predictable limits. More broadly, it provides conceptual support for understanding how limit behavior can be derived from constraints rather than direct evaluation.

It is especially powerful in dealing with functions that oscillate yet remain bounded within predictable limits.

A graph of x² sin(1/x) showing rapid oscillations that shrink toward the x-axis near zero, demonstrating how an oscillating function can remain bounded within narrowing limits. Source.

FAQ

The Squeeze Theorem is especially effective for functions with unpredictable or oscillatory behaviour whose exact limits cannot be found by algebraic simplification.

Common examples include:

• Trigonometric expressions with shrinking amplitudes

• Oscillatory functions confined by simple bounding curves

• Functions defined piecewise or implicitly whose formula does not directly reveal limit behaviour

It is particularly useful when the function's values become tightly constrained near a point, even if the overall expression appears complex.

No. The bounding functions only need to be easier to analyse than the function being squeezed, not necessarily simple in form.

They must:

• Be defined in a neighbourhood around the point

• Have known or easily computable limits

• Maintain a consistent inequality relationship

Even complicated bounding functions are acceptable as long as their limits match and the inequalities hold near the target point.

The inequalities must hold in some open interval around the point, regardless of whether they hold at the exact point itself.

This interval can be very small and does not need to be symmetric. The critical requirement is that the function stays between its bounds for all sufficiently close values, allowing the shared limit of the bounding functions to force the same limit on the squeezed function.

Yes, provided the inequalities hold in a neighbourhood around the point and the bounding functions share the same limit.

Single points of intersection do not affect validity. What matters is:

• A consistent bounding relationship near the point

• Matching limits of the bounding functions

• The middle function remaining between those bounds as it approaches the point

Touching at a single point does not break these conditions.

Look for clues indicating a function is difficult to evaluate directly but is naturally constrained. Typical signs include:

• Oscillation that decreases in amplitude

• Products of a bounded expression with one that approaches zero

• Piecewise or implicit definitions that obscure direct substitution

• Statements or inequalities provided in the problem

When a problem explicitly gives inequalities, it is often a prompt that the Squeeze Theorem may be the intended method.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is defined for all x near 0, and satisfies

x squared less than or equal to f(x) less than or equal to 2x squared for all x close to 0.

Given that the limit as x approaches 0 of x squared is 0, determine the value of the limit as x approaches 0 of f(x).

Explain your reasoning.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Correctly identifies that both bounding functions have limit 0 as x approaches 0.

1 mark: States that f(x) is squeezed between these functions.

1 mark: Concludes that the limit of f(x) as x approaches 0 is 0, with clear justification.

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is defined for all x near 3 and satisfies

h(x) less than or equal to g(x) less than or equal to k(x),

where the functions h and k satisfythe limit as x approaches 3 of h(x) is 5

the limit as x approaches 3 of k(x) is 5.

(a) Using the Squeeze Theorem, determine the limit as x approaches 3 of g(x).

(b) A student claims that the limit of g(x) might not exist because the value g(3) is undefined. State whether the student is correct and justify your answer.

(c) Another student suggests that the inequalities need to hold at x = 3 for the Squeeze Theorem to apply. Evaluate this statement and explain your reasoning.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

1 mark: States that h(x) and k(x) both approach 5 as x approaches 3.

1 mark: Identifies that g(x) is bounded between h(x) and k(x).

1 mark: Concludes that the limit of g(x) as x approaches 3 is 5 by the Squeeze Theorem.

(b)

1 mark: States that the student is incorrect.

1 mark: Explains that the existence of the limit does not depend on the value g(3); limits depend only on behaviour near the point.

(c)

1 mark: States that the inequalities do not need to hold at x = 3, only near 3.

1 mark: Explains that the Squeeze Theorem requires bounding behaviour in a neighbourhood of the point, not at the point itself.

Total: 6 marks