AP Syllabus focus:

‘Construct appropriate upper and lower bound functions in order to apply the squeeze theorem to more complicated functions and determine their limits.’

Developing reliable upper and lower bounds allows students to extend the Squeeze Theorem to increasingly complex functions, enabling precise limit evaluation when direct computation is difficult.

Constructing Bounds to Squeeze Other Functions

Understanding the Goal of Bounding

When applying the Squeeze Theorem, the objective is to find two simpler functions that trap a more complicated function between them near a point of interest.

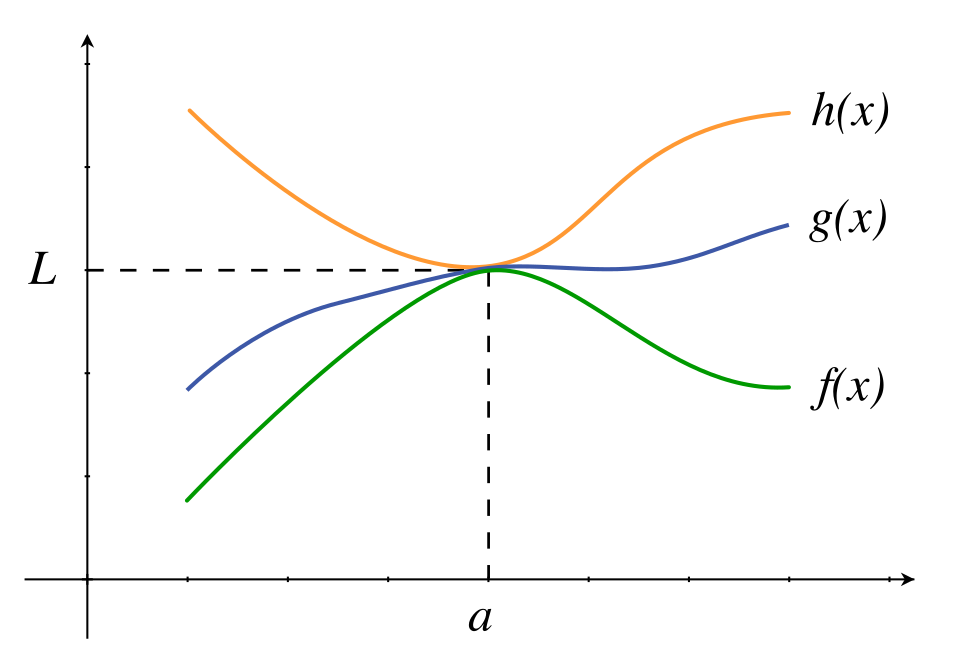

A generic graph illustrates the Squeeze Theorem: the middle function is trapped between upper and lower curves that converge toward the same limit as approaches , visually reinforcing the concept of bounding to determine limits. Source.

These bounding functions must be easier to analyze and share a known limit at the target input. Because complicated expressions often behave predictably within specific intervals, bounding becomes a strategic way to reveal hidden limit behavior.

The Squeeze Theorem as a Guiding Principle

Before constructing bounds, it is essential to understand the purpose of bounding: to reliably compare a function to others whose limit behavior is already established. This comparison validates the desired limit without explicitly computing the original function’s limit algebraically or numerically.

Squeeze Theorem: If for near , and , then .

Once the theorem frames the goal, constructing useful bounds becomes a matter of identifying structure in the function and matching it to known inequalities.

Strategies for Constructing Upper and Lower Bounds

Bounding is not guesswork—it uses recognized function properties, inequalities, and structural patterns.

Common strategies include:

Using known trigonometric inequalities such as , which extend naturally to compositions like or .

Leveraging absolute value properties, especially for functions known to stay within fixed bounds.

Comparing growth behaviors, where one function dominates another as approaches a limiting value.

Expanding inequalities through algebraic manipulation, such as multiplying by positive expressions to maintain direction.

Bounding oscillatory factors by enclosing them within constants so that only the non-oscillating part influences the limit.

Recognizing When Bounds Are Needed

Some functions resist direct substitution or simplification. Bounding becomes necessary when:

A factor oscillates indefinitely, preventing normal limit evaluation.

A term approaches zero, allowing the possibility of forcing the product or quotient toward a known limit.

A function’s graph suggests constrained behavior but its algebraic form is too complex.

The function’s structure includes composition with known bounded functions.

These conditions signal that a bounding approach may reveal the limit more effectively than algebra alone.

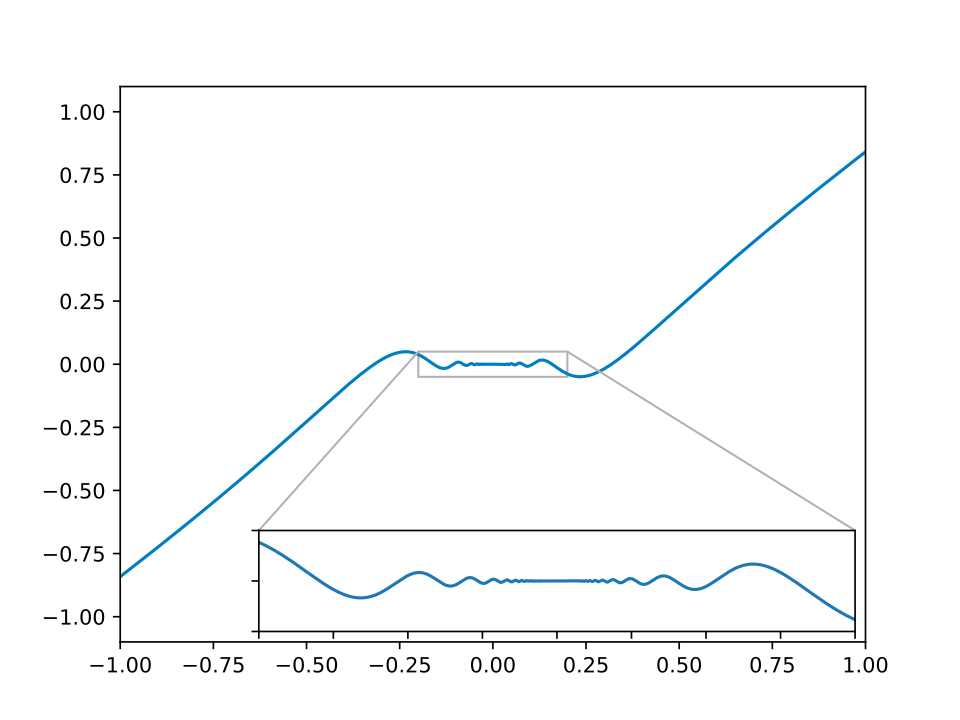

The graph of displays rapid oscillations with diminishing amplitude near , illustrating how an oscillatory term multiplied by a shrinking factor becomes a natural candidate for bounding when applying the Squeeze Theorem. Source.

Building Bounds from Known Inequalities

Constructing bounds often begins with establishing a basic inequality that applies to a crucial part of the function. Once the base inequality is identified, it can be transformed or extended to enclose the entire expression.

Key techniques include:

Substituting transformed expressions into known inequalities.

Multiplying inequalities by positive expressions to scale bounds appropriately.

Incorporating absolute values to control sign-sensitive terms.

Using algebra to reshape the inequality into one that matches the function’s structure.

Bounded Function: A function is bounded near if there exists a number such that for all sufficiently close to .

Recognizing bounded components immediately suggests how they may contribute to a three-function inequality required for the Squeeze Theorem.

Combining Bounds with Limit Behavior

After bounding the function, the next requirement is to ensure that both bounding functions approach the same limit at the desired point. At this stage, the Squeeze Theorem converts the bounding relationship into a precise limit statement.

= Lower bounding function

= Common limit value

A bounding inequality allows the conclusion only when the upper and lower bounding functions converge identically.

A bounding argument typically proceeds as follows:

Identify a bounded or oscillatory term.

Recognize a factor that approaches zero or another simple behavior.

Apply a known inequality to the oscillatory term.

Multiply or combine inequalities to form a complete bound.

Evaluate limits of the bounding functions.

Use the Squeeze Theorem to justify the limit of the target function.

Structural Patterns That Help in Constructing Bounds

Certain algebraic and trigonometric structures commonly appear in limit problems and lend themselves naturally to bounding. Recognizing these structures streamlines the bounding process.

Helpful patterns include:

Oscillating factor multiplied by shrinking factor, ensuring that the shrinking factor determines the limit.

Reciprocal expressions that amplify or diminish bounded terms.

Products of bounded and monotonic functions, allowing the monotonic portion to guide the limit.

Exponential or polynomial envelopes that dominate smaller oscillatory components.

Interpreting Bounding Graphically and Conceptually

Even though bounding is an analytic technique, a conceptual or graphical understanding strengthens intuition. Visualizing two curves tightening around the target function near the limit point reinforces why the Squeeze Theorem works and how well-constructed bounds reveal true function behavior.

FAQ

An inequality holds near a limit point if all algebraic steps used to construct it preserve order. Multiplying or dividing by a positive expression always maintains inequality direction, which is essential when building bounds.

If the sign of an expression is uncertain, rely on absolute values to guarantee correctness. This ensures that your bounding functions genuinely enclose the target function.

Oscillatory functions often remain trapped within fixed numerical bounds, even as their frequency increases. This makes them ideal when paired with another factor that approaches zero.

Because the oscillation does not settle to a single value, direct limit evaluation fails. Bounding supplies the structure needed to reveal the underlying limiting behaviour.

Yes. A bound does not need to be sharp to be useful; it only needs to converge to the same limit as its counterpart.

Loose bounds still demonstrate that the target function is confined between two functions approaching a common value. This is often sufficient for applying the Squeeze Theorem successfully.

Break the function into components and analyse each separately. Identify which part is bounded, which part approaches zero, and which part controls the overall behaviour.

Useful approaches include:

• Isolating oscillatory terms

• Using absolute values to simplify sign issues

• Multiplying known inequalities by appropriate factors

This layered method often reveals a workable bounding structure.

A graph can reveal amplitude shrinkage, oscillation patterns, or natural envelopes around a function. These visual cues suggest what types of functions could serve as upper and lower bounds.

While graphs do not provide formal proof, they guide algebraic reasoning by highlighting behaviour that may not be obvious from the expression alone.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is defined for all x close to 0, and it is known that

-1 <= sin(3/x) <= 1 for all nonzero x,

and that f(x) = x sin(3/x).

Using suitable bounds, determine lim x→0 f(x).

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• Identifies suitable bounds: -x <= f(x) <= x or equivalent (1 mark)

• States that both bounding functions tend to 0 as x→0 (1 mark)

• Concludes that the limit is 0 by the Squeeze Theorem (1 mark)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Let g be a function defined by

g(x) = x^2 cos(1/x) for x ≠ 0,

and g(0) = 0.

(a) Show that g(x) is bounded above and below by two functions whose limits at 0 are easy to evaluate.

(b) Hence determine lim x→0 g(x).

(c) Explain briefly why the Squeeze Theorem is required in this situation rather than direct substitution.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• Uses the fact that -1 <= cos(1/x) <= 1 to give -x^2 <= g(x) <= x^2 (1 mark)

• States or implies that these are appropriate bounding functions (1 mark)

(b)

• Correctly evaluates both bounding limits as 0 (1 mark)

• Concludes that lim x→0 g(x) = 0 by the Squeeze Theorem (1 mark)

(c)

• Explains that cos(1/x) oscillates infinitely often near 0, preventing direct substitution (1 mark)

• States that bounding is necessary to control the oscillation and justify the limit (1 mark)