AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rewrite verbal descriptions of function behavior near a point as formal limit statements, choosing appropriate symbols and notation to match the described behavior.’

Verbal descriptions of nearby function behavior can be rewritten precisely using limit notation, allowing us to express approaching values symbolically and interpret function behavior with mathematical clarity.

Translating Verbal Descriptions into Limit Notation

Translating verbal descriptions into formal limit statements is a central skill in AP Calculus AB because it builds the bridge between everyday language and precise mathematical communication. A limit describes the value a function approaches as the input approaches a number, even if the function never actually attains that value. To express this symbolically, students must understand how to interpret verbal cues about approaching behavior, directionality, and function values.

Understanding Key Phrases in Verbal Descriptions

Verbal statements often hint at how a function behaves near a point without explicitly stating a limit. Recognizing these cues helps determine which symbols and expressions to use. Common verbal features include:

A variable approaching or getting arbitrarily close to a value.

A function getting close to, approaching, or tending toward a number.

References to behavior near a point rather than at the point.

Indications of direction, such as “from the left” or “from the right.”

When interpreting these, it is essential to distinguish between the function’s value at a point (if it exists) and the limit, which depends only on nearby behavior.

The Meaning of Formal Limit Notation

Before writing formal expressions, recall that limit notation expresses the idea of approaching behavior without requiring equality at the point.

Limit of a Function: The value a function approaches as its input approaches a specified number, regardless of whether the function equals that value at the number.

When a verbal description references behavior from one side, it corresponds to one-sided limits, which use special notations indicating direction.

Writing Two-Sided Limits from Verbal Descriptions

Two-sided limits arise when the verbal description implies that the function approaches the same value from both sides of a point. Typical verbal cues include:

“As x gets closer to c …”

“When x approaches c …”

“The function approaches L near c …”

These translate into the standard symbolic form:

A two-sided limit statement communicates a complete description of nearby behavior, even if the function value at differs or is undefined.

“When a verbal statement says that as xxx gets arbitrarily close to ccc, the outputs get arbitrarily close to LLL, the corresponding analytic notation is a two-sided limit.”

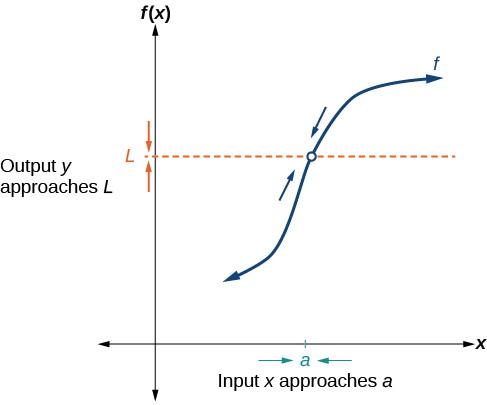

This graph illustrates a function whose values approach a single height LLL as the input xxx approaches aaa from both directions, even though the function is not defined at that point. It visually represents the verbal description that the output nears LLL as xxx nears aaa. The hole emphasizes that limits describe nearby behavior rather than the value of the function at the point itself. Source.

Writing One-Sided Limits from Verbal Descriptions

When the verbal statement specifies direction, the limit must reflect this using left- or right-hand notation. Cues such as “as x approaches c from values less than c” indicate a left-hand limit, written . Phrases such as “from values greater than c” correspond to the right-hand limit, written .

These distinctions are crucial for describing functions with behaviors such as jumps or asymmetrical approaches.

“If a verbal description distinguishes the behavior ‘from the left’ and ‘from the right’ of ccc, you should write one-sided limits using limx→c−f(x)\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x)limx→c−f(x) and limx→c+f(x)\lim_{x \to c^+} f(x)limx→c+f(x) rather than a single two-sided limit.”

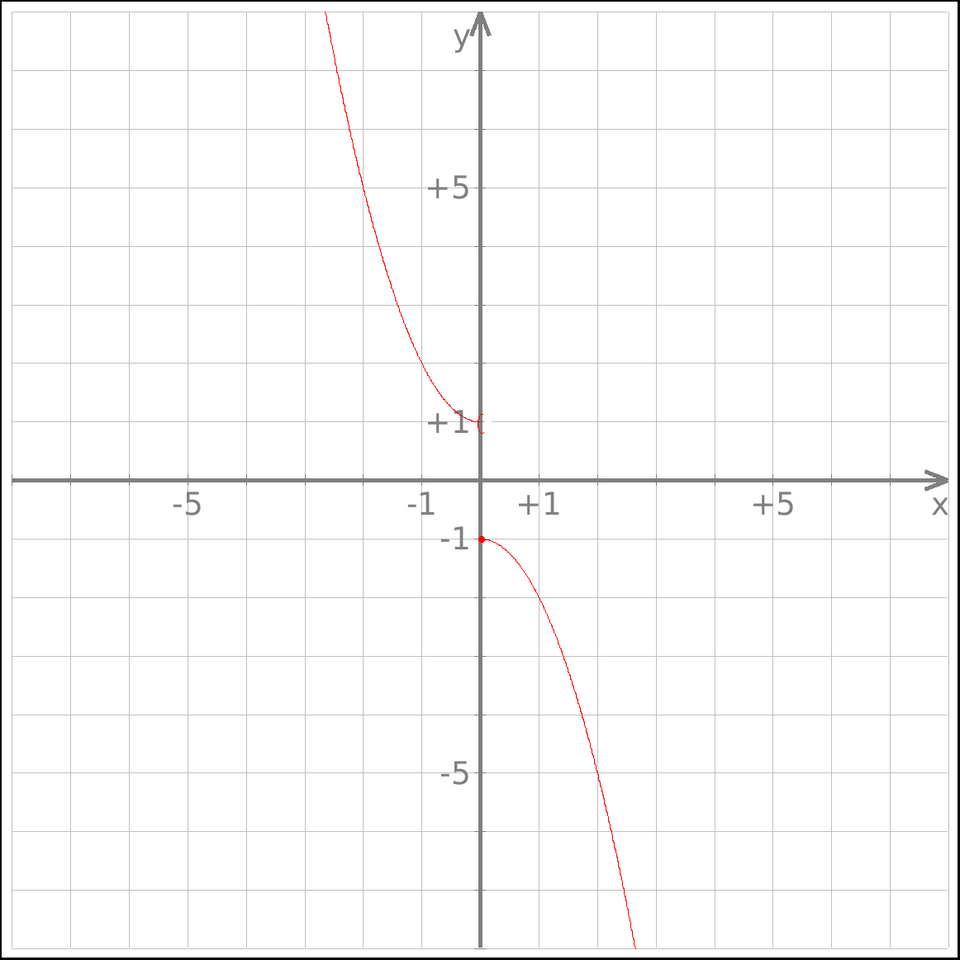

This graph shows a function that approaches one value as xxx approaches the target point from the left and a different value from the right. It visually supports verbal descriptions requiring one-sided limit notation such as limx→c−f(x)\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x)limx→c−f(x) and limx→c+f(x)\lim_{x \to c^+} f(x)limx→c+f(x). Although the overall limit does not exist, the directional behavior highlights why one-sided notation is essential for translating verbal statements accurately. Source.

Connecting Behavior to Appropriate Symbol Choices

To translate statements accurately, students must match language to notation carefully. Consider the following layers of interpretation:

A statement describing how the function output behaves suggests the limit’s value.

A statement about where x is heading determines the approach point.

A statement referencing direction determines whether the limit is one-sided.

A statement emphasizing behavior near but not at a point signals that the limit—not the function value—is the appropriate tool.

Using correct limit notation ensures that the mathematical meaning is communicated without ambiguity.

Structured Approach to Translation

The process of converting verbal descriptions into limit notation becomes more reliable when students follow a consistent method:

Identify the input behavior: What value is x approaching?

Identify the output behavior: What value does the function approach?

Determine one-sided or two-sided behavior based on directional words.

Translate into symbolic notation using appropriate limit symbols.

These steps reinforce conceptual understanding and align directly with the expectations of the AP Calculus AB curriculum.

Incorporating Precision and Clarity in Limit Statements

Limit notation is powerful because it conveys precise information about function behavior. To maintain clarity:

Use correct symbols, including arrows, superscripts, and function notation.

Distinguish between equals (used for numerical values) and approaches (expressed via limit notation).

Avoid implying that the limit evaluates the function at that point unless explicitly stated.

This careful separation of ideas mirrors the broader calculus theme that limiting behavior often reveals deeper insights than pointwise values.

Relating Verbal Descriptions Across Representations

Though this subsubtopic focuses on translating verbal descriptions into limit notation, it is helpful to recognize that verbal descriptions commonly arise from graphical or numerical contexts. Students may hear descriptions such as “the graph levels off near L” or “the values in the table approach 3,” both of which signal limit structure. Translating these to symbols strengthens fluency across representations and prepares students for more advanced topics in differential calculus.

Understanding how to express verbal descriptions using formal limit notation enhances mathematical communication and deepens conceptual mastery in early calculus study.

FAQ

Verbal descriptions that focus on behaviour near a point, rather than at the point, always indicate a limit. Phrases such as “gets closer to”, “approaches”, or “tends towards” signal limiting behaviour.

If the statement instead uses wording like “the function is equal to” or “the value at x = c”, it is describing the function value, not a limit.

Language that specifies direction is the key indicator. Look for phrases such as:

• “from values greater than c”

• “approaching from below”

• “approaches c from the left/right”

If direction is not implied, assume a two-sided limit is intended.

Many descriptions deliberately exclude the point because limits concern only nearby behaviour. The function value at the point may be irrelevant, undefined, or even contradictory.

In translation tasks, your focus is solely on what happens as x approaches the point, not what happens exactly at it.

If the description indicates that behaviour differs by direction, not by speed, write separate one-sided limits.

If the rate or path affects the outcome in a more complex expression, focus on whether the description distinguishes approach directions explicitly. Without directional cues, you cannot assume one-sided limits are intended.

Yes. Descriptions such as “approaches one value from the left and another from the right” or “oscillates near the point” imply non-existence of a limit.

In these cases, translate each described behaviour into appropriate symbolic statements, even if the overall two-sided limit fails to exist.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is described verbally as follows:

"As x approaches 2, the values of f(x) get closer and closer to 7, regardless of whether x approaches from the left or from the right."

Write a single mathematical statement in limit notation that accurately represents this behaviour.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for writing a limit expression involving x approaching 2.

• 1 mark for writing the correct function notation f(x).

• 1 mark for giving the correct limit value 7.

Correct answer: lim x→2 f(x) = 7

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is described verbally as follows:

"As x approaches 4 from values greater than 4, the outputs of g(x) approach 12. However, when x approaches 4 from values less than 4, the outputs approach 3. The function value g(4) is defined to be 10."

(a) Write two separate mathematical statements in limit notation describing the behaviour of g(x) as x approaches 4 from the left and from the right.

(b) State, with justification, whether the two-sided limit of g(x) as x approaches 4 exists.

(c) Explain whether g is continuous at x = 4.

Mark scheme:

(a)

• 1 mark for correct right-hand limit notation with limit value 12.

• 1 mark for correct left-hand limit notation with limit value 3.

(b)

• 1 mark for stating that the two-sided limit does not exist.

• 1 mark for correct justification: the left and right limits are not equal.

(c)

• 1 mark for stating that g is not continuous at x = 4.

• 1 mark for correct explanation: continuity requires the limit to exist and equal g(4); here the limit does not exist, so continuity fails.