AP Syllabus focus:

‘Give examples of continuous functions that are not differentiable at certain points in their domain, such as corners or cusps where left-hand and right-hand derivatives differ.’

Functions can behave smoothly overall yet fail to possess a derivative at specific points. Understanding how continuity differs from differentiability is essential for identifying nondifferentiable behavior in graphs.

Continuous but Not Differentiable

A function can be continuous at a point yet fail to be differentiable there, meaning the graph connects without breaks but lacks a well-defined instantaneous rate of change. This subsubtopic emphasizes recognizing specific graph features—particularly corners, cusps, and mismatched one-sided derivatives—that obstruct differentiability even when continuity is preserved.

When a function is continuous at , its limit matches its function value. However, differentiability requires the limit of the difference quotient to exist and be the same from both sides. The derivative fails whenever this condition is violated despite continuity.

Understanding Continuity Versus Differentiability

Continuity ensures no jumps, gaps, or removable breaks in the graph. Differentiability is a stronger requirement tied to smoothness of change, so any abrupt directional shift can prevent the derivative from existing. Points of concern typically occur where the graph abruptly changes slope or approaches an infinite steepness.

Continuous at a Point: A function is continuous at if .

Because continuous functions can still display sharp visual features, continuity alone cannot guarantee differentiability at the same location.

One-Sided Derivatives and Their Role

To determine differentiability at a point, AP Calculus AB students must analyze one-sided derivatives, which measure instantaneous rate of change from each direction. If these values disagree or fail to exist, the ordinary derivative is undefined even when the function itself remains unbroken.

One-Sided Derivative: The left-hand derivative and right-hand derivative are limits of the difference quotient taken from and respectively.

A disagreement in these two directional values signals the presence of a corner or cusp. Even a momentary shift in slope renders the tangent line undefined or ambiguous.

Corners

A corner is a point on a function’s graph where the slope from the left and the slope from the right differ but both remain finite. Graphically, the function appears to form a sharp angle. Corners commonly arise in piecewise-defined functions where the pieces connect continuously but exhibit distinct slopes.

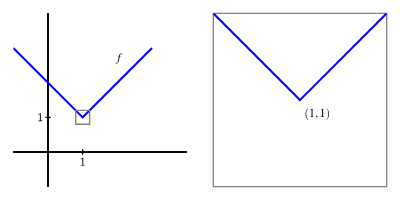

This graph shows a function that is continuous at but has a sharp corner there, so does not exist. The left and right sides of the curve meet at , yet they approach that point with different finite slopes, preventing a single tangent line. This visual underscores that continuity alone does not guarantee differentiability at a point. Source.

Important features of corners include:

The function does not break; the point is continuous.

The tangent line cannot be uniquely defined because directional slopes conflict.

The derivative is undefined at that point due to mismatch in one-sided derivatives.

Cusps

A cusp represents an even sharper feature than a corner, often where the slopes on each side diverge to opposite infinities. While the function remains continuous, the instantaneous rate of change becomes unbounded as the graph rapidly changes direction.

Cusp: A point where the graph of a continuous function approaches vertical tangency with slopes tending toward opposite infinite values on each side.

Cusps highlight how continuity does not constrain slope behavior; steepness can become extreme without breaking the graph.

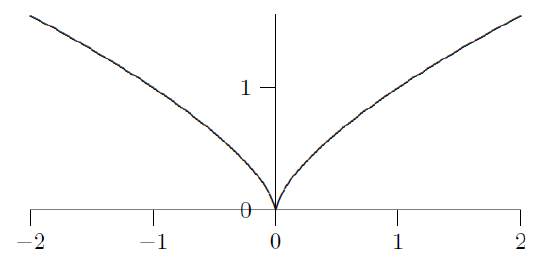

This graph of shows a cusp at , where the function remains continuous but the tangent slope becomes unbounded from both sides. As approaches , the curve turns sharply and the tangent lines approach a vertical line, so no finite derivative exists at the cusp. This example emphasizes that even without gaps or jumps, extreme changes in direction can destroy differentiability. Source.

Vertical-Like Sharpness and Infinite Slopes

Some nondifferentiable points involve behavior approaching a vertical slope without forming a point of vertical tangency. The key issue is abrupt directional change rather than actual vertical alignment. In cusps or corners, slopes become undefined not because the tangent line is vertical, but because competing directional behaviors prevent forming a single linear approximation.

These features emphasize the need to treat differentiability as a limit-based property rather than a purely visual one.

Analyzing Graphs for Nondifferentiability

Students should examine three core aspects when deciding whether a continuous function is nondifferentiable at a point:

Directional Slopes: Do the left-hand and right-hand rates of change match?

Smoothness: Does the graph flow gently through the point, or does it shift abruptly?

Local Behavior: Does the function exhibit signs of unbounded steepness as it approaches the point?

If any of these indicators fail, differentiability fails even when continuity is confirmed.

Why the Derivative Fails to Exist

The derivative represents the instantaneous slope of the tangent line, which itself must be unique. At corners, multiple tangent line candidates exist. At cusps, steepness becomes unbounded, eliminating the possibility of a finite slope. In both cases, the limit defining the derivative fails to converge to a single real number.

= Function value at the point

= Increment approaching zero

As the limit fails to settle to a single finite value in these situations, the point is deemed nondifferentiable.

Key Indicators of Continuity Without Differentiability

Students can rely on the following identifying features:

Continuous connection with no gaps at the point.

Sharp geometric features such as corners or cusps.

Mismatched or divergent one-sided derivatives.

Absence of a single, well-defined tangent line.

FAQ

A corner usually forms when two line segments or curves meet with different but finite slopes, creating a clear angled point. In contrast, a cusp shows a sharper, more dramatic change in direction.

A practical way to tell them apart:

• Corners have finite slopes on both sides.

• Cusps have slopes that grow extremely large in magnitude, often appearing almost vertical as you zoom in.

Yes. A function may have a well-defined derivative on one side of the point if the limit of the difference quotient exists when approaching from that direction.

However, differentiability at the point itself still fails because:

• The opposite side does not produce the same derivative value, or

• The derivative on the other side does not exist or diverges.

Many real-world situations involve sudden changes in behaviour, including shifts in direction, speed, or applied forces. These transitions often generate non-smooth features in mathematical models.

Common examples include:

• Absolute value relationships in optimisation

• Sudden changes in material resistance

• Piecewise rules in cost or penalty structures

Often, yes. By smoothing transitions or replacing sharp joins with gently curving segments, modellers can create differentiable approximations.

This is common in:

• Computer graphics

• Physics simulations

• Economic modelling

Such adjustments preserve the general shape while eliminating problematic corners or cusps.

They can. If a function with a corner or cusp is used inside another function, the non-differentiability usually propagates through the composition.

Key considerations:

• A composite cannot be differentiable at a point where the inner function fails to be differentiable.

• Even if the outer function is smooth, the composite inherits the inner function’s sharp behaviour at that input.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The graph of a continuous function f is shown to have a sharp corner at x = 2.

Explain why f is not differentiable at x = 2.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: States that the left-hand and right-hand derivatives at x = 2 do not agree.

1 mark: States that a sharp corner means there is no single tangent line at that point.

1 mark: Concludes that f is not differentiable at x = 2 because the derivative does not exist.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is continuous on the interval [−3, 3]. Near x = 0, the graph of g displays a cusp: as x approaches 0 from the left, the slope of the graph becomes increasingly large and positive; as x approaches 0 from the right, the slope becomes increasingly large and negative.

(a) State what feature of the graph ensures that g is continuous at x = 0.

(b) Explain why g is not differentiable at x = 0.

(c) Describe how the behaviour of the slopes near x = 0 demonstrates the difference between continuity and differentiability.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Part (a)

1 mark: Identifies that the graph is unbroken or connected at x = 0, or that the limit of g(x) as x approaches 0 equals g(0).

Part (b)

1 mark: States that the slopes on each side of x = 0 become unbounded or diverge.

1 mark: States that the left-hand and right-hand derivatives do not agree or do not exist.

1 mark: Concludes that g is not differentiable at x = 0 because there is no finite tangent slope.

Part (c)

1 mark: Explains that continuity concerns the value of the function being unbroken, whereas differentiability requires a well-defined slope.

1 mark: States that extreme or opposing slopes show the graph is continuous but not smooth, so differentiability fails.