AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain that if a function is differentiable at a point, then it must be continuous there; if a point is not in the domain of f, it cannot be in the domain of f′.’

Differentiability and continuity are closely connected ideas in calculus, and understanding their relationship clarifies when derivatives exist and how functions behave at specific input values.

Differentiability and Its Consequences

A function is differentiable at a point when its derivative exists there, meaning the limit defining the instantaneous rate of change converges to a single real number. Differentiability guarantees that the function behaves in a locally predictable and smooth manner. The derivative captures how rapidly the output changes with respect to the input and reflects the function’s local linearity.

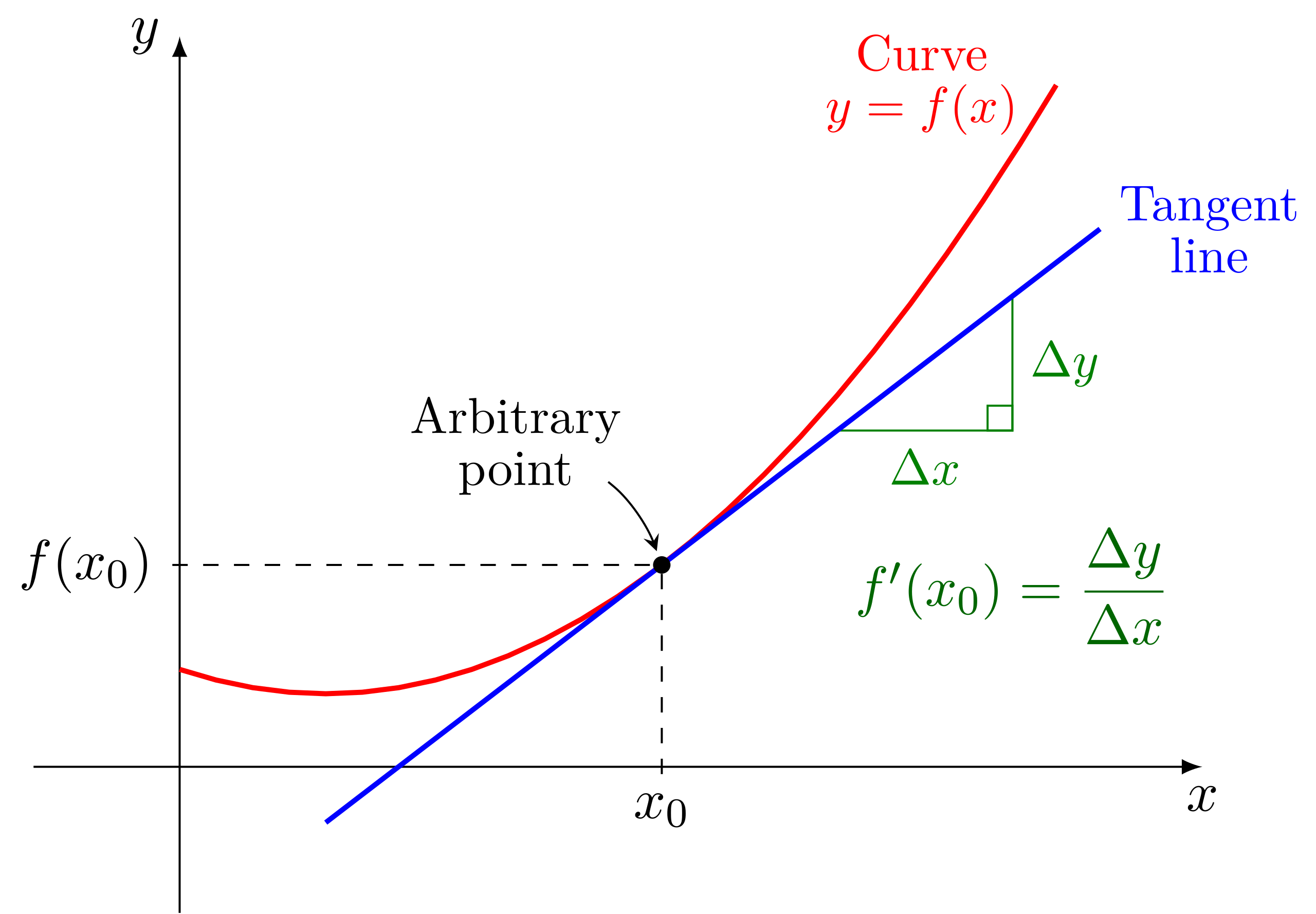

This diagram shows a smooth graph of with a tangent line drawn at a point , illustrating that differentiability at corresponds to a single, well-defined slope. The tangent line’s slope represents the derivative , emphasizing that differentiable functions locally resemble their tangent lines. The image reinforces that such local linearity cannot occur if the function is discontinuous at the point. Source.

Differentiability: A function is differentiable at a point if the limit of its difference quotient exists and is finite.

Because differentiability ensures a consistent slope around the point, it has important implications for continuity. Differentiability is a stronger condition than continuity, meaning that when a derivative exists at a point, the function cannot “jump,” break, or behave erratically there. This relationship forms a foundational principle in AP Calculus AB.

Continuity as a Prerequisite

A function is continuous at a point when its value, limit, and behavior align without any gaps. When a point is in the domain of a function, the input is valid, and the function assigns an output value. Only then is it meaningful to discuss continuity or differentiability. Understanding this structure helps clarify why differentiability cannot occur without continuity.

Continuity: A function is continuous at if .

In order for a derivative to exist, the function must not only approach a definite value but do so in a way that supports a well-defined slope. This requirement integrates continuity into the broader concept of differentiability.

Why Differentiability Implies Continuity

The AP syllabus emphasizes the crucial statement: if a function is differentiable at a point, it must be continuous there. Differentiability imposes structure on the function’s nearby values, enforcing smoothness that prevents discontinuities.

= derivative at , representing instantaneous rate of change

= change in input approaching

= change in output over the interval

Because this limit exists only when approaches in a stable and predictable manner, the condition forces the limit of the function to equal the function’s actual value at . Therefore, continuity becomes a necessary consequence of differentiability. Stated differently, if a function exhibited a discontinuity at , the difference quotient would not stabilize to a single slope value, and the derivative could not exist.

A normal sentence such as this one ensures proper spacing before the next structural element.

Domain Considerations and the Derivative

The syllabus also specifies that if a point is not in the domain of a function, it cannot be in the domain of its derivative. This reflects the logical sequence required for differentiability. Since defining a derivative depends on evaluating and for values arbitrarily close to , the function must be defined on an interval around that point.

Domain: The set of all input values for which a function is defined.

If a point is excluded from the domain, the function provides no output there, making continuity impossible and eliminating the possibility of a derivative.

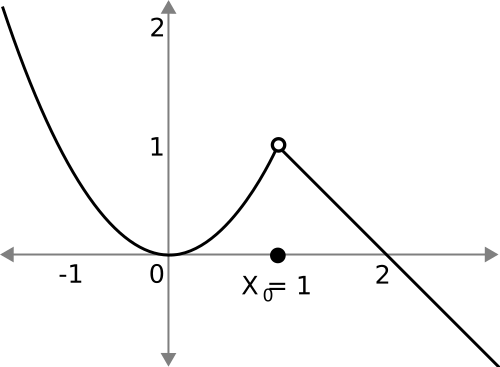

This graph shows a curve with a hole at , representing a removable discontinuity where the function is not defined at that input. Because does not exist, the function cannot be continuous or differentiable at , even though nearby values follow a simple trend. The image emphasizes that domain membership is required before continuity or derivatives can be considered. Source.

This rule prevents attempting to assign derivative values at holes, vertical asymptotes, or locations where the function simply does not exist. It underscores that the derivative function is built directly upon the original function’s structure.

A sentence here provides separation before further conceptual clarification.

Structural Relationship Between the Function and Its Derivative

The derivative function inherits its domain from where is differentiable, which is always a subset of where is continuous and defined. Because continuity is required but not sufficient for differentiability, students should view the hierarchy as:

Differentiability requires continuity.

Continuity requires the point to be in the domain.

Therefore, differentiability requires the point to be in the domain.

This structure ensures that each concept builds on the previous one. A function may be continuous without being differentiable, but it can never be differentiable without being continuous. This perspective helps students recognize situations where a derivative must fail, such as at discontinuities or undefined points, aligning precisely with the AP curriculum’s emphasis.

FAQ

Continuity only ensures that a function has no gaps or jumps at a point, whereas differentiability requires the function to behave smoothly enough to possess a well-defined slope there.

A function may be continuous yet have features such as sharp corners or abrupt directional changes. These do not violate continuity but prevent the existence of a unique tangent slope, making differentiability the stricter condition.

No. Differentiability requires that both the left-hand and right-hand derivatives exist and agree. If a function is continuous only from one side, it cannot provide the two-sided behaviour necessary to define a derivative.

You may still consider one-sided derivatives, but these do not count as differentiability in the full sense required for AP Calculus AB.

If the function is not continuous at a point, the numerator of the difference quotient reflects a sudden jump or undefined value, preventing the quotient from approaching a single finite limit.

Patterns that may appear include:

• The difference quotient blowing up to extremely large magnitudes.

• Oscillating values that never stabilise.

• Being impossible to compute because the function value at the point does not exist.

Sometimes continuity can be restored by redefining the function at a removable discontinuity, but this does not automatically restore differentiability.

Even after filling the hole, the surrounding behaviour must still support a stable, unique derivative. If the graph approaches the point in a non-smooth way, differentiability will still fail.

Forming a derivative requires evaluating how the function behaves arbitrarily close to the point of interest. If the function is not defined at the point itself, the derivative cannot be computed.

This reflects the hierarchy:

• A point must be in the function’s domain to discuss continuity.

• Continuity must hold to discuss differentiability.

• Thus, differentiability is impossible anywhere the function itself does not exist.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function g is differentiable at x = 2.

(a) State what this implies about the continuity of g at x = 2.

(b) Explain why g must be defined at x = 2 for the derivative g'(2) to exist.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: States that differentiability at x = 2 implies continuity at x = 2.

(b) 1–2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that g must be defined at x = 2 to discuss continuity or differentiability.

• 1 mark for explaining that the derivative requires evaluating g(2) and nearby values, so g(2) must exist.

Total: 2–3 marks available.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function h defined on the real numbers except at x = 5, where it has a removable discontinuity. The limit of h(x) as x approaches 5 exists and is finite, but h(5) is not defined.

(a) Explain why h cannot be differentiable at x = 5.

(b) A student claims that because the graph of h appears smooth on both sides of x = 5, the derivative at x = 5 should still exist. Evaluate this claim, giving a clear reason based on differentiability and continuity.

(c) Describe the relationship between differentiability, continuity, and the domain of a function that this example illustrates.

Question 2

(a) 1–2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that h is not continuous at x = 5.

• 1 mark for concluding that since differentiability implies continuity, h cannot be differentiable at x = 5.

(b) 1–2 marks:

• 1 mark for rejecting the claim.

• 1 mark for explaining that even a visually smooth graph cannot compensate for a missing function value; the derivative cannot be formed because the function is undefined at x = 5.

(c) 2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that differentiability requires continuity.

• 1 mark for stating that continuity requires the point to be in the domain, so differentiability is impossible at points where the function is not defined.

Total: 4–6 marks available.