AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize that a function can fail to be differentiable at a point where the tangent line is vertical and has no finite slope, even though the function is continuous there.’

Vertical tangents reveal moments where a function’s graph rises or falls infinitely steeply, creating continuity without differentiability because no finite slope can describe the instantaneous rate of change.

Understanding Vertical Tangents in Differentiation

A vertical tangent occurs when the graph of a function becomes infinitely steep at a point. In such cases, the tangent line is vertical, meaning its slope is undefined. Because the derivative represents the slope of the tangent line, the derivative cannot exist at any point where the tangent line is vertical.

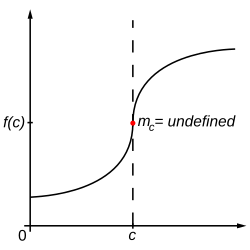

This graph shows a curve with a vertical tangent line at a specific point, illustrating how the slope becomes infinite. The function remains continuous at the point even though the derivative does not exist. This highlights the distinction between continuity and differentiability when a tangent becomes vertical. Source.

This aligns directly with the AP requirement to recognize that a function may remain continuous while still failing to be differentiable at such points.

When a tangent line is vertical, the instantaneous rate of change approaches positive or negative infinity. Even though the function’s value approaches a clear limit, the change in output with respect to input becomes unbounded. This leads to a breakdown in differentiability, despite the absence of breaks, jumps, or holes in the graph.

Differentiability vs. Continuity at Points with Vertical Tangents

A function can be continuous while not differentiable, and vertical tangents are a key example. The function does not “jump” or “break”; instead, its slope simply becomes too steep to express with a finite number. Students should distinguish these ideas clearly, because AP Calculus AB emphasizes that failing to be differentiable does not imply failing to be continuous.

Differentiability: A function is differentiable at a point if its derivative exists there, meaning the limit of its difference quotient approaches a finite value.

A vertical tangent provides a special case where the limit governing the derivative does exist in a directional sense but diverges to infinity or negative infinity. This signals that the slope cannot be represented by a finite real number.

How Vertical Tangents Arise

Vertical tangents typically appear when the function’s rate of change accelerates without bound near a point. This often happens when the denominator in a difference quotient shrinks faster than the numerator, creating increasingly steep secant lines.

Before reaching the exact point of the vertical tangent, the slopes of secant lines become extremely large, either positive or negative. These slopes do not settle toward a single finite value as the interval shrinks, so differentiability fails.

= instantaneous rate of change at

= small change in input

In the case of a vertical tangent, this limit diverges rather than approaching a finite value.

A limit that diverges still describes meaningful geometric behavior: the graph becomes vertical. However, because the derivative requires a finite real number to exist, such divergence ensures non-differentiability.

Graphical Interpretation of Vertical Tangents

Students must be able to recognize vertical tangents visually.

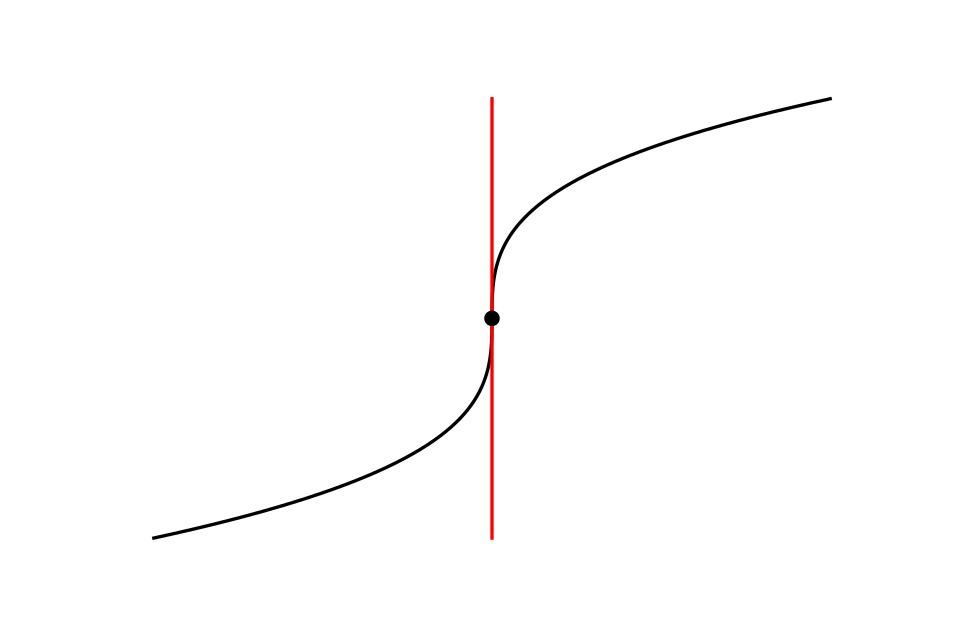

This diagram shows the cube root function together with a vertical tangent at the origin, where the slope becomes unbounded. The function remains continuous at this point even though the derivative does not exist. The visual emphasizes infinite steepness as the cause of non-differentiability. Source.

Key graphical indicators include:

The function approaches a nearly vertical orientation near the point.

The left-hand and right-hand slopes both become unbounded, but not necessarily with opposite signs.

The function remains connected and unbroken at the point of interest.

Because continuity concerns only the function's value and limit, not its slope, the function may still be continuous even as its slope becomes infinite.

Why a Vertical Tangent Implies Non-Differentiability

For a derivative to exist, both the left-hand and right-hand limits of the difference quotient must approach the same finite number. At a vertical tangent, the slopes approach infinity or negative infinity, meaning they cannot satisfy the condition for differentiability.

Non-differentiability: A function is non-differentiable at a point when the derivative fails to exist, often due to discontinuities, corners, cusps, or vertical tangents.

In contrast with corners or cusps, which arise from abrupt directional changes, vertical tangents arise from unbounded steepness. Yet all such situations prevent differentiability.

Distinguishing Vertical Tangents from Other Non-Differentiable Features

Recognizing different types of non-differentiability is essential:

Corners: One-sided slopes exist but differ.

Cusps: One-sided slopes diverge to opposite infinities.

Vertical tangents: One-sided slopes diverge to the same infinity (positive or negative), creating infinite steepness.

Each of these behaviors produces a point where the derivative does not exist, but the geometric cause differs.

Analytical Clues for Identifying Vertical Tangents

While no explicit calculations are required here, students should understand qualitative indicators that a function may have a vertical tangent:

The derivative expression involves terms that cause the slope to grow without bound as approaches a point.

The function's rate of change accelerates dramatically as inputs near the point.

Graphing technology reveals increasingly steep slopes in the region.

These clues help confirm that the tangent line becomes vertical and the derivative fails to exist, even though the function remains continuous.

FAQ

A vertical tangent occurs when the slope grows without bound as you approach the point, not merely when the graph looks steep.

To verify this, check whether the secant slopes approach very large positive or negative values without levelling off. If they continue increasing without stabilising, the tangent is vertical.

• If estimates appear to settle to a large finite value, the slope is steep but not vertical.

• If estimates escalate indefinitely, the slope is unbounded and the tangent is vertical.

Not necessarily. Vertical tangents commonly involve slopes approaching infinity from both sides, but some functions can approach infinite slope from only one direction while the other side remains undefined or does not exist.

This still prevents differentiability because the derivative requires both one-sided limits to exist and be equal.

Yes, a function may have several vertical tangents, often arising when the rate of change accelerates dramatically near multiple points.

Common mechanisms include:

• Repeated factors in algebraic expressions that produce unbounded growth.

• Rapid approach to a limiting value within an oscillatory or root-type structure.

• Symmetry in functions such as certain power roots that steepen at multiple locations.

Numerical derivative tools use difference quotients over very small intervals. Near a vertical tangent, dividing by a tiny change in x amplifies rounding error, causing unstable or inconsistent outputs.

Graphing calculators may also auto-rescale axes, making the curve appear less steep than it truly is. This can hide the behaviour leading to a vertical tangent unless the window is adjusted manually.

Yes. Vertical tangents persist under vertical or horizontal shifts and reflections because these transformations do not alter steepness.

However, vertical or horizontal stretches can change where the steepness becomes infinite.

• A vertical stretch may steepen the curve more quickly, shifting the point where a vertical tangent occurs.

• A horizontal stretch may slow steepening, potentially removing or relocating a vertical tangent.

The fundamental behaviour, though, remains rooted in how rapidly the function’s rate of change grows.

Practice Questions

A function f is continuous at x = 2. A graph of f near x = 2 shows the curve becoming vertical as it approaches the point (2, f(2)). Explain why f is not differentiable at x = 2.

(1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies that the tangent line at x = 2 is vertical or that the slope becomes infinite.

• 1 mark: States that the derivative cannot exist because the slope is not finite or does not approach a finite limit.

• 1 mark: Connects this to non-differentiability, e.g. “Therefore f is not differentiable at x = 2.”

Maximum 3 marks.

Consider the function g defined for all real x by g(x) = cube root of (x – 1).

(a) Show that g has a vertical tangent at x = 1.

(b) Explain clearly why g is continuous at x = 1 but not differentiable there.

(c) State one other feature of a graph that can cause a function to be continuous but not differentiable.

(4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Observes that as x approaches 1, the graph becomes infinitely steep or the slope grows without bound.

• 1 mark: Concludes that the tangent at x = 1 is vertical.

(b)

• 1 mark: States that g is continuous at x = 1 because the limit of g(x) as x approaches 1 equals g(1).

• 1 mark: States that g is not differentiable because the slope becomes infinite or the derivative does not approach a finite limit.

(c)

• 1 mark: Gives a correct feature such as a corner, cusp, or discontinuity in the derivative.

Maximum 6 marks.