AP Syllabus focus:

‘Apply the power rule to find derivatives of polynomial terms with positive and negative integer exponents in symbolic and applied problems.’

The power rule provides a fast, reliable method for differentiating expressions involving integer powers of the variable, forming the foundation for efficient derivative computation in calculus.

Applying the Power Rule to Integer Powers

The power rule is a fundamental differentiation rule that dramatically simplifies finding the derivative of functions expressed as integer powers of . It allows students to bypass the limit definition of the derivative in favor of a direct algebraic method appropriate for polynomial expressions and terms involving both positive and negative integer exponents.

Understanding Integer Powers within Differentiation

Before applying the rule, it is important to recognize how integer powers behave within differentiable expressions. An integer power is any expression of the form , where is a whole number or its negative counterpart. These powers appear frequently in polynomial functions, rational expressions, and real-world models where quantities scale proportionally with repeated multiplication or division.

Integer Power: An expression of the form where is any positive or negative integer.

Students should be aware that positive powers model repeated multiplication, whereas negative powers represent reciprocal relationships. This distinction makes the power rule especially efficient because it applies uniformly across these different representations.

The Power Rule for Derivatives

The power rule states that the derivative of is obtained by multiplying by the exponent and reducing the exponent by one. This transformation reflects how the instantaneous rate of change of a power function depends on both its exponent and its current value.

= any integer exponent

= independent variable

Because this rule is universally valid for integer exponents, it enables rapid symbolic differentiation of polynomial terms and supports the interpretation of how these expressions change with respect to their inputs.

This rule is essential in both symbolic work and applied problems where the derivative represents a measurable quantity such as velocity, growth rate, or marginal change.

Differentiating Positive Integer Powers

Positive integer powers, such as or , appear frequently in polynomial functions. When differentiating such terms, applying the power rule directly yields new polynomial expressions of reduced degree. This process reveals important structural properties of polynomials, including predictable behavior of successive derivatives and the effect of exponent reduction on curvature.

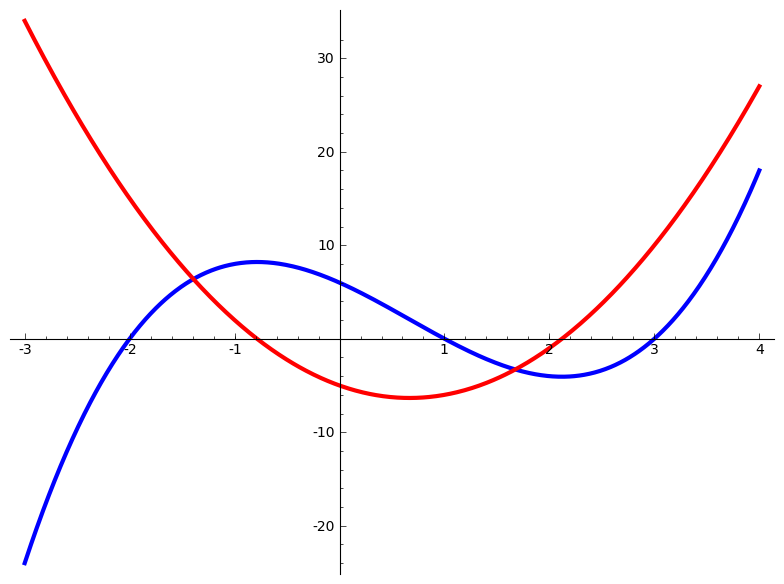

This graph shows a cubic polynomial together with its quadratic derivative, illustrating how applying the power rule reduces degree and determines curvature behavior. Source.

Differentiating Negative Integer Powers

Negative integer powers, including expressions like or , may initially appear different because they represent reciprocal functions.

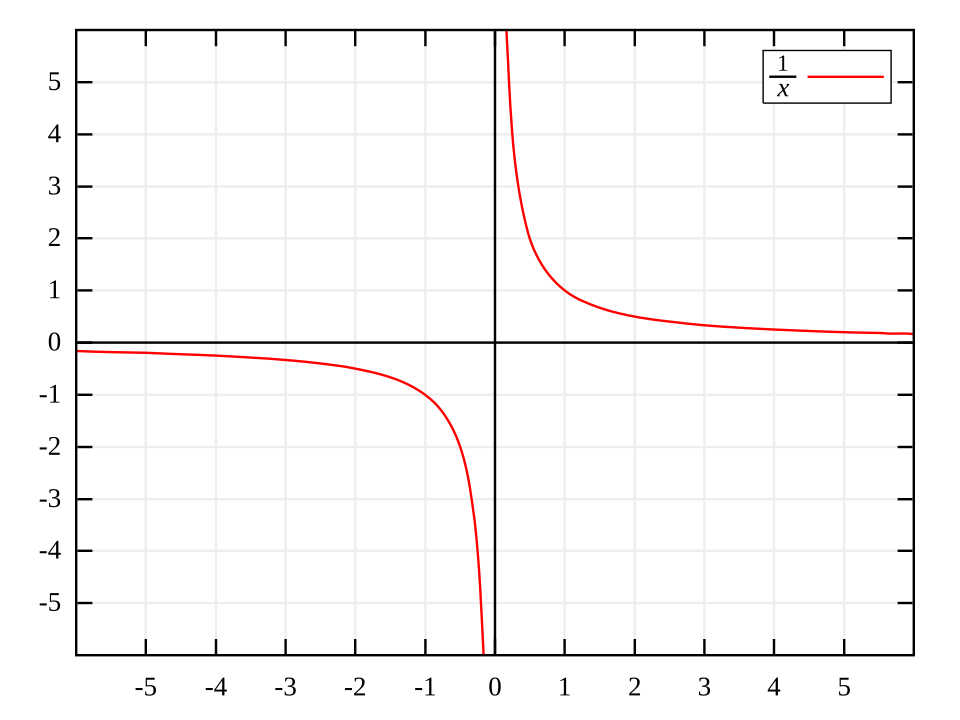

The graph illustrates the reciprocal function y=1/xy = 1/xy=1/x, a model of a negative integer power. Its asymptotic structure highlights characteristic behavior of reciprocal functions that still follow the power rule for differentiation. Source.

Nevertheless, the same power rule applies without modification. When the exponent decreases by one, the resulting expression typically involves a higher-order reciprocal, which is consistent with the behavior of rational functions and their rates of change.

Reciprocal Power: A power function of the form , representing for a positive integer .

These reciprocal forms commonly emerge in contexts involving inverse proportionality, and the power rule provides a direct way to differentiate them without first rewriting them as fractions.

Importance of Symbolic Accuracy

Careful symbolic manipulation is an essential component of applying the power rule correctly. The exponent must be lowered by exactly one, and the coefficient multiplying the variable must be evaluated precisely. Small symbolic inaccuracies—such as mishandling negative signs or omitting the new exponent—can produce significant errors in later steps of a problem, particularly when derivatives are used to determine graphical or physical behavior.

Power Rule in Applied Problems

In applied settings, the derivative of a function involving integer powers often represents an instantaneous rate of change connected to a real-world quantity. The power rule’s efficiency supports rapid evaluation of such rates, enabling students to interpret results within meaningful contexts such as motion, economics, or population modeling. Because many models simplify to polynomial or rational forms, having a reliable method to compute derivatives of integer powers is crucial for understanding how related quantities evolve.

Integration with Other Differentiation Rules

Although the focus of this subsubtopic is on applying the power rule to individual terms, students should recognize that it frequently works in combination with other derivative rules. When dealing with polynomials or more complex expressions, the power rule is applied to each term individually while sum, difference, and constant multiple rules determine how these differentiated terms combine. This integration allows for efficient differentiation of a wide range of functions encountered in AP Calculus AB.

FAQ

The power rule applies whenever the expression is a single term whose variable is raised to an integer exponent, including negative integers.

If the expression can be written as a constant multiplied by x to some integer power, the rule applies immediately. Terms involving sums, products, or non-integer powers require other differentiation rules.

The decrease arises from the structure of repeated multiplication. Each differentiation step removes one factor of x from the original expression.

This reflects how the rate of change of x raised to an integer power depends on how many repeated factors contribute to growth.

Yes—negative integer powers create reciprocal behaviour, and as x gets smaller in magnitude, the function’s value grows in magnitude.

This occurs because dividing by a very small number produces large outputs, which also leads to rapid changes detectable through differentiation.

Differentiation affects each term individually, but their relative magnitudes can shift.

For example, lower-degree terms may become more or less dominant after differentiation, altering the overall shape or steepness of the resulting expression.

Rewriting is optional, but it can clarify algebraic structure.

Some students find fractional form easier when checking domain restrictions or simplifying final answers, but the power rule works the same in either representation.

Practice Questions

The function f is defined by f(x) = 7x^5 − 3x^2.

(a) Find f′(x).

(1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of 7x^5 is 35x^4.

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of −3x^2 is −6x.

• 1 mark: Final answer f′(x) = 35x^4 − 6x.

A particle moves along a line such that its position at time t seconds is given by

s(t) = 4t^6 − 2t^3 + 15.

(a) Use the power rule to find the velocity function v(t).

(b) Determine the acceleration at t = 2.

(c) State one interpretation of the sign of the acceleration at this instant.

(4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a) Velocity

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of 4t^6 is 24t^5.

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of −2t^3 is −6t^2.

• 1 mark: Final velocity expression v(t) = 24t^5 − 6t^2.

(b) Acceleration at t = 2

• 1 mark: Differentiate velocity to obtain a(t) = 120t^4 − 12t.

• 1 mark: Correct substitution of t = 2 and correct evaluation of the numerical result.

(c) Interpretation

• 1 mark: Correct statement that the sign of the acceleration indicates whether the particle’s velocity is increasing (positive acceleration) or decreasing (negative acceleration) at t = 2.