AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rewrite radical expressions using rational exponents and use the power rule to find derivatives, interpreting these derivatives using graphs and verbal descriptions.’

Extending the power rule to rational exponents strengthens students’ ability to differentiate a wider class of functions by converting radicals into exponent form and applying familiar derivative rules.

Understanding Rational Exponents and Differentiability

Rational exponents allow functions written with radicals to be expressed in a more flexible algebraic form. When expressed with exponents, such functions can be differentiated using the power rule, which states that the derivative of is for appropriate values of . This subsubtopic focuses on rewriting radical expressions as rational powers and applying differentiation rules consistently and accurately, supporting deeper interpretation of rates of change in graphical and contextual settings.

Rational Exponent: An exponent written as a fraction , representing the th root of a quantity raised to the th power.

When dealing with radical expressions, converting them to rational exponents enables direct application of derivative rules used earlier for integer powers. This supports algebraic simplification and strengthens conceptual understanding of instantaneous change.

Rewriting Radical Expressions Using Rational Exponents

Students must be able to rewrite expressions involving square roots, cube roots, and other radicals into exponent form. This transformation is essential for applying the power rule without relying on memorized derivative formulas for special cases.

Examples of common conversions include:

rewritten as

rewritten as

rewritten as

These rewritten expressions better reveal structural features of a function, such as growth or decay behavior, and prepare the function for differentiation using rules already mastered with integer exponents.

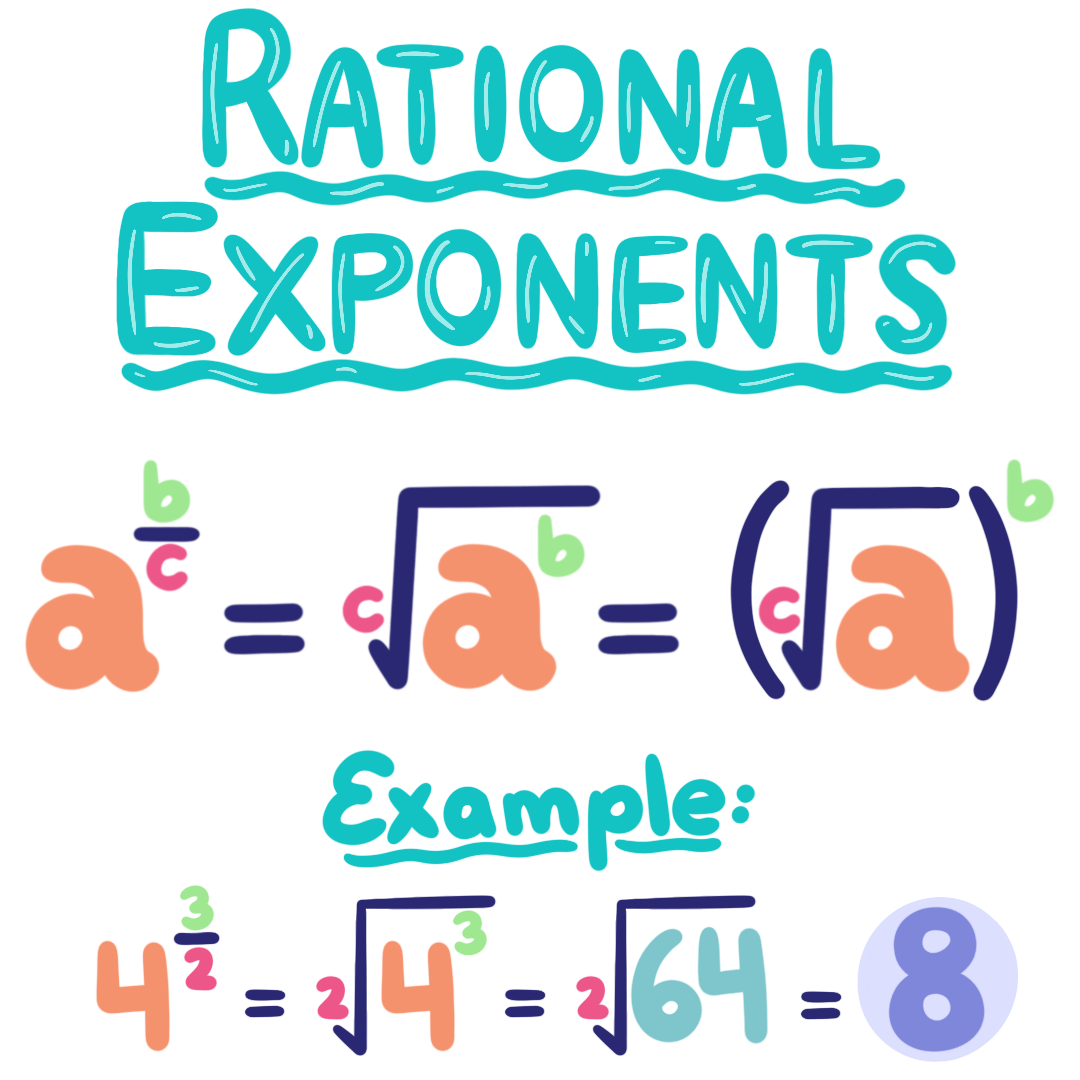

This diagram illustrates the equivalence between rational exponents and radical expressions, reinforcing how fractional powers translate into roots and powers in symbolic form. The example included provides additional detail but supports the same conceptual relationship. Source.

= numerator determining the power applied

= denominator determining the root applied

Shifting a function into rational exponent form does not alter its meaning but clarifies its structure for calculus operations.

Applying the Power Rule to Rational Exponent Functions

The power rule extends naturally to rational exponents, allowing derivatives to be computed for a broader class of functions than those expressed with integers alone. Differentiating functions of the form follows the same pattern used for polynomial expressions.

= any real exponent for which the function is differentiable

Using rational exponents, the derivative of a function involving radicals becomes algebraically straightforward.

Key characteristics of applying the power rule with rational exponents include:

The new exponent becomes , which may also be rational or negative.

The resulting derivative may include reciprocal or radical forms.

Algebraic simplification often improves interpretability, especially when relating results to the behavior of graphs.

A critical skill is identifying when a rational exponent expression reveals domain restrictions that shape where the derivative exists.

Interpreting Derivatives Using Graphs and Verbal Descriptions

Interpreting the meaning of derivatives obtained from rational exponent functions is central to AP-style reasoning. After differentiating, students must relate the resulting expression to graphs and contextual features of the function.

Important interpretive insights include:

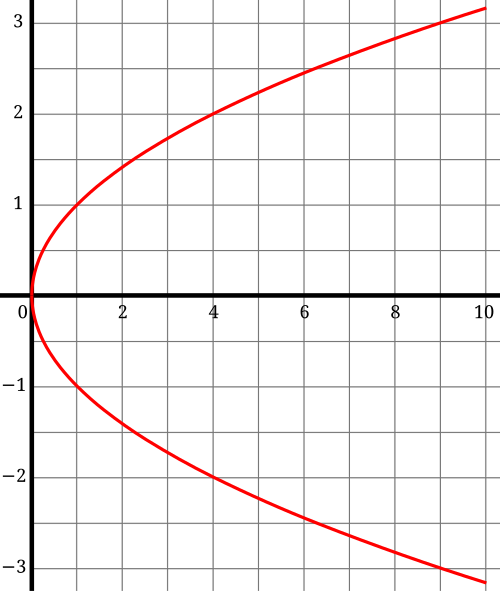

Slope behavior: The sign and magnitude of indicate increasing or decreasing behavior and rate of steepness.

Concavity cues: Although second derivatives are not the focus here, recognizing when a rational exponent leads to rapid growth or flattening helps connect symbolic and graphical understanding.

Domain and continuity considerations: Rational exponents may restrict where the original function and its derivative are defined, affecting interpretation on graphs.

These interpretations support essential calculus reasoning about motion, accumulation, and real-world change when functions are modeled using radical or rational exponent expressions.

This graph displays the function y=xy=\sqrt{x}y=x, illustrating the restricted domain and the changing slope characteristic of rational-exponent functions. Though it does not depict the derivative explicitly, it provides a clear visual context for understanding instantaneous change. Source.

Process for Extending the Power Rule to Rational Exponents

To apply the power rule successfully in this context, the following steps provide a reliable structure aligned with the syllabus expectations:

Rewrite all radical expressions using rational exponent notation to ensure compatibility with differentiation rules.

Identify the exponent clearly, confirming whether it is positive, negative, or fractional.

Apply the power rule by multiplying by the current exponent and reducing the exponent by one.

Simplify the result algebraically, converting back into radical form only when beneficial for interpretation.

Interpret the derivative verbally or graphically when required, focusing on instantaneous rate of change.

Strengthening Conceptual Understanding Through Consistent Notation

The transition from radical notation to rational exponent notation is more than a symbolic change. It clarifies structural relationships within functions and promotes flexible thinking. As students become proficient in expressing functions in exponent form, they develop stronger command over derivative operations and deepen their conceptual understanding of instantaneous change.

FAQ

Rewriting a radical as a rational exponent transforms the function into a standard power format, allowing the power rule to be applied uniformly without introducing extra algebraic steps.

It also clarifies the structure of the function, making exponent manipulation more transparent and reducing the likelihood of errors during differentiation.

Yes, but only when the expression is mathematically defined. For example:

• Even roots require non-negative inputs.

• Odd roots allow negative inputs.

• Negative rational exponents introduce reciprocal expressions, which may further restrict the domain by excluding zero.

Understanding these restrictions ensures correct interpretation of where both the function and its derivative exist.

The size of the new exponent after differentiation determines how quickly the derivative grows or decays.

A larger positive exponent indicates faster increases in rate of change, while negative exponents highlight intervals where the rate of change becomes very small or approaches infinity.

Most cases benefit from conversion, but exceptions occur when:

• The radical form is already simple enough that the derivative is obvious.

• The expression involves multiple operations where converting may create unnecessary algebraic complexity.

In general, the exponent form is preferred for clarity and consistency.

Rational exponents often represent physical or geometric relationships, such as area–radius or volume–length scaling.

Expressing these relationships as power functions makes it easier to analyse growth patterns, compare rates of change, and describe how small variations in input influence the output in measurable contexts.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

A function is given by f(x) = 4x^(3/2).

(a) Rewrite f(x) using radical notation.

(b) Find f ’(x).

Question 1 (2 marks)

(a) 1 mark: Correct rewriting using radicals

• f(x) = 4 sqrt(x^3)

(or equivalently 4 x sqrt(x))

(b) 1 mark: Correct derivative

• f ’(x) = 4 * (3/2) x^(1/2) = 6 x^(1/2)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Consider the function g(x) = 2x^(5/3) − 3x^(2/3).

(a) Rewrite g(x) entirely in radical form.

(b) Differentiate g(x).

(c) Explain briefly how the derivative reflects the rate of change of g(x) for x > 0.

Question 2 (5 marks)

(a) 1 mark: Correct radical expressions

• g(x) = 2 cube_root(x^5) − 3 cube_root(x^2)

(b) 2 marks:

• 1 mark for differentiating each term correctly

• g ’(x) = 2 (5/3) x^(2/3) − 3 (2/3) x^(-1/3)

• Simplified: g ’(x) = (10/3) x^(2/3) − 2 x^(-1/3)

(c) 2 marks: Explanation of rate of change for x > 0

• 1 mark: Recognises that the derivative is positive for sufficiently large x, implying increasing behaviour

• 1 mark: Notes that the term with x^(-1/3) becomes small as x increases, so the overall rate of change increases gradually