AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain what a limit found using L’Hospital’s Rule tells you about the behavior of the original functions near the point, connecting the result to the contextual meaning of the quantities.’

Understanding how to interpret a limit computed with L’Hospital’s Rule is essential for connecting symbolic results to real-world behavior, especially when functions represent meaningful, measurable quantities in context.

Interpreting L’Hospital’s Rule in Applied Contexts

L’Hospital’s Rule provides a powerful way to evaluate limits that initially yield indeterminate forms, but the deeper skill required in this subsubtopic is explaining what the computed limit tells us about how two quantities behave near a specific point. In contextual problems, the ratio of two functions frequently represents a meaningful comparison—such as efficiency, density, rate ratios, or relative growth—and the limit describes how these relationships behave as the independent variable approaches a critical value.

When students apply L’Hospital’s Rule, they must interpret the meaning of the resulting limit rather than viewing it as merely a numerical outcome. An interpretation connects the limit to the real-world significance of the functions involved and clarifies what the ratio reveals about their behavior.

Understanding What the Limit Represents

The limit of a ratio of two functions often answers a conceptual question such as “How does one quantity compare to another as we approach a particular condition?” or “What trend emerges when both quantities approach zero or infinity?” A result found using L’Hospital’s Rule therefore carries contextual meaning tied directly to the structure of the original scenario.

When this ratio involves derivatives, the behavior is described in terms of instantaneous rates of change, which provides additional insight into how the related quantities evolve.

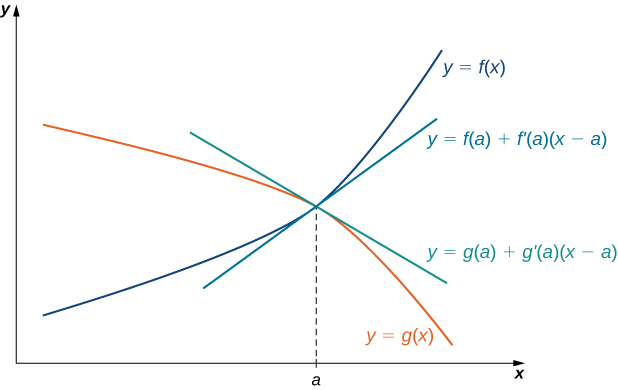

This diagram compares two functions and their tangent-line approximations near x=ax=ax=a. It illustrates how the ratio f(x)/g(x)f(x)/g(x)f(x)/g(x) behaves like the ratio of slopes f′(a)/g′(a)f'(a)/g'(a)f′(a)/g′(a) close to the point. The linear-approximation detail slightly exceeds AP requirements but reinforces the geometric foundation of L’Hospital’s Rule. Source.

Instantaneous Rate of Change: The derivative of a function at a point, representing how fast the dependent variable is changing with respect to the independent variable at that instant.

This interpretation is especially useful in scientific or economic contexts, where the magnitude of a rate ratio may reveal dominance, proportionality, or equilibrium between two interacting quantities.

A normal sentence is required here before any equation appears, ensuring clarity and coherence of the conceptual explanation.

= Numerator function representing a measurable quantity

= Denominator function representing a related measurable quantity

= Limit describing how the ratio behaves as approaches

Practical Meaning of the Limit in Context

Interpreting a limit requires translating the symbolic value into a precise statement about the original situation.

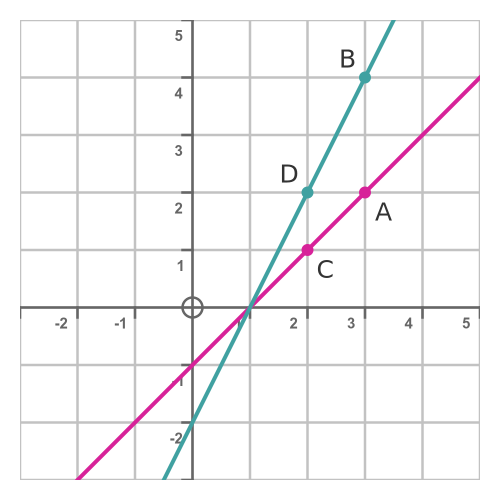

This graph illustrates how two functions approaching zero together can produce a stable limiting ratio as xxx approaches a shared intercept. The consistent values of f(x)/g(x)f(x)/g(x)f(x)/g(x) near the point highlight how a limit describes the behavior of the quotient even when the ratio is undefined at the intercept. The labeled points add contextual clarity beyond AP expectations but remain conceptually aligned. Source.

The meaning typically relates to one or more of the following ideas:

Relative behavior near the point

Does one quantity grow faster than another?

Is the ratio stabilizing toward a constant value?

Description of trends

A finite limit indicates a predictable relationship between the two quantities as the input approaches the specified value.

A limit of zero suggests the numerator quantity becomes negligible compared with the denominator.

A limit approaching infinity indicates the numerator dominates sharply.

Contextual explanation using appropriate units

Since both functions carry units, the limit inherits a contextual unit or becomes unitless depending on the structure of the ratio. This unit must be identified when interpreting the meaning.

Connecting Limit Values to Real Situations

A limit found using L’Hospital’s Rule should always be interpreted in the language of the applied setting. This involves explicitly stating:

What each function represents in the original problem.

What the limit describes about their relationship.

How the result reflects actual behavior of the modeled situation.

For example, if the ratio of two biological or physical quantities approaches a constant, the limit describes how those quantities compare as conditions converge. If the ratio gives a rate-based value, the interpretation should reference how rapidly one measured property changes relative to another at that instant.

Communicating Meaningful Interpretations

Clear communication of the result includes identifying changing quantities, stating what the limit reveals about their relationship near the specified point, and describing the implication for the scenario. Important elements of a complete interpretation include:

Naming the relevant quantities rather than referring to them abstractly.

Stating the direction of change, such as increasing, decreasing, or leveling off.

Connecting the numerical limit directly back to the phenomenon being modeled.

Checklist for Interpreting L’Hospital’s Rule in Context

To ensure interpretations are thorough and contextually accurate, students should verify that they have:

Identified what the numerator and denominator represent.

Connected the form of the original limit (such as or ) to the situation.

Explained the meaning of comparing rates of change when derivatives appear.

Provided appropriate units or explained why the ratio is unitless.

Described what the limit reveals about the behavior of the modeled quantities near the given point.

Why Interpretation Matters

Interpreting the result ensures that the mathematical process answers the actual contextual question, providing an explanation that describes how the original quantities are behaving—not merely how the symbolic expression behaves.

FAQ

Computing the limit gives a numerical result, but interpretation requires translating that number into a meaningful statement about the original quantities in context.

This involves explaining what the numerator and denominator represent, how their behaviours compare near the specified point, and what the limit indicates about their real-world relationship.

No. The interpretation applies only near the point where the limit is evaluated.

It provides local information about how the two quantities behave as the input approaches the specific value, not how they behave far from that point or over extended intervals.

It may mean:

• The ratio of the quantities becomes highly unstable near the specified point.

• The numerator and denominator grow or shrink in incompatible ways.

• The situation requires a more detailed model or another analytical method.

In context, this often signals a rapid or unpredictable change in the relationship between the quantities.

The limit may have meaningful units, depending on the context. If the numerator and denominator measure quantities with different units, the ratio inherits a compound unit.

Units help determine whether the limit represents:

• A pure comparison of magnitudes

• A rate-based interpretation

• A dimensionless proportion

This ensures the explanation remains physically or practically meaningful.

Yes. A limit can reveal whether one quantity begins to dominate another, whether they stabilise relative to each other, or whether a key transition occurs.

For example, a small limit may indicate diminishing influence of the numerator quantity, whereas a large limit suggests increasing dominance or sensitivity near the specified point.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The functions p(x) and q(x) model two related physical quantities. As x approaches 2, both p(x) and q(x) approach 0, creating an indeterminate form in the ratio p(x)/q(x). Using L’Hospital’s Rule, it is found that the limit of p(x)/q(x) as x approaches 2 equals 5.

Explain what this limit value tells you about the behaviour of the original quantities p and q near x = 2.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for stating that the limit describes how p compares to q near x = 2.

• 1 mark for interpreting the value 5 as meaning p is changing five times as fast as q near x = 2.

• 1 mark for noting that the meaning refers to the original quantities, not the derivatives alone.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A population model gives two functions, A(t) and B(t), representing two interacting species. As t approaches 10 weeks, both A(t) and B(t) approach zero, but their ratio is difficult to evaluate directly. Applying L’Hospital’s Rule gives the result:

limit of A(t)/B(t) as t approaches 10 equals 0.25.

(a) Explain what this limit tells you about the behaviour of the two populations near t = 10.

(b) State one reason why this interpretation must be expressed in terms of the original populations rather than the derivatives alone.

(c) Briefly describe what the limit value would suggest if it had instead been greater than 1.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for stating that the limit gives the comparative behaviour of A and B near t = 10.

• 1 mark for interpreting 0.25 as A decreasing to zero at a quarter of the rate of B (or B decreasing four times as fast as A).

• 1 mark for explaining that L’Hospital’s Rule replaces the ratio of functions with the ratio of their instantaneous rates of change, which must be tied back to the original quantities for contextual meaning.

• 1 mark for identifying that derivatives alone describe rates, not the real-world quantities being compared.

• 1 mark for stating that if the limit were greater than 1, A would be decreasing faster than B near t = 10 (or A dominates relative to B).

• 1 mark for clarity and correct use of contextual reasoning.