AP Syllabus focus:

‘Integrate each term in a partial fraction decomposition separately, often resulting in logarithmic antiderivatives for linear denominators.’

Integrating decomposed rational functions allows complex rational expressions to be rewritten as simpler, separate terms whose antiderivatives follow directly from foundational integration rules studied in AP Calculus AB.

Understanding Integration After Decomposition

When a rational function has already been rewritten as a sum of simpler fractional components, the next step is to integrate each term individually. This approach is grounded in the property that the integral of a sum equals the sum of integrals, enabling a difficult expression to be evaluated using familiar antiderivative rules. In this subsubtopic, the emphasis falls on linear denominators, which most commonly lead to logarithmic antiderivatives.

Because many rational functions do not resemble basic integrable forms at first glance, partial fraction decomposition is an algebraic tool applied beforehand. Once the function is split into simpler parts, the calculus step becomes accessible, efficient, and closely aligned with the AP standard.

This perspective—that a complicated expression can be written as a sum of simpler fractions—is the foundation for integrating decomposed rational functions.

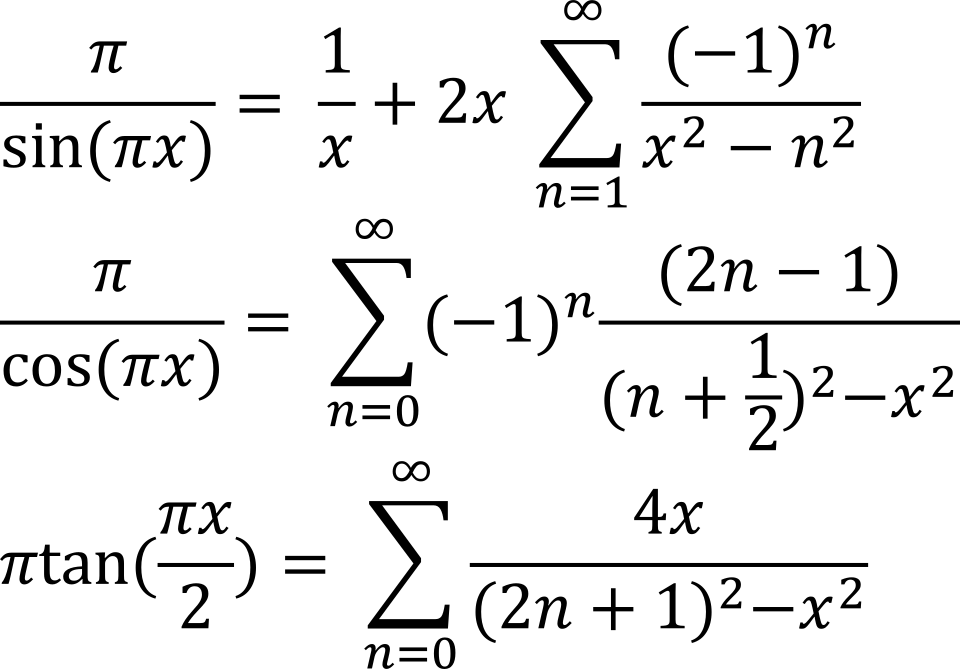

Diagram summarizing partial fraction decompositions for various trigonometric functions, illustrating how complex expressions can be rewritten as sums of simpler terms. The figure includes trigonometric cases beyond the AP Calculus AB syllabus, but the decomposition structure shown is directly analogous to rational-function decomposition. The visual reinforces the conceptual basis of simplifying algebraic forms before integrating. Source.

Key Idea: Integrating Term-by-Term

Integrating decomposed rational functions relies on the linearity of the integral, which allows the integral to be distributed across each simplified term.

Bullet points highlighting the fundamental process:

Begin with a rational function already expressed as a sum of simple fractions.

Identify the type of each denominator, focusing here on nonrepeating linear factors.

Apply basic antiderivative rules to each term independently.

Combine the results while including the constant of integration for indefinite integrals.

Maintain awareness of domain restrictions implied by logarithmic expressions.

The integrals resulting from linear denominators most often involve natural logarithms. This reflects the general behavior of integrals of the form , extended via substitution to handle shifts and scalings in the denominator.

Integrating Linear Denominators

A decomposed term with the structure or becomes straightforward to integrate using known antiderivatives. When this type appears in a rational decomposition, the calculus step typically involves recognizing that the derivative of the denominator is constant, allowing an immediate logarithmic expression.

= Constant obtained from decomposition

= Coefficient of the linear term

= Constant term in the linear expression

This antiderivative form appears frequently in AP Calculus AB and is essential for handling rational expressions after decomposition. Students should become fluent in identifying when an integrand matches this structure.

A clear contrast exists between integrating decomposed linear denominators and nonlinear or irreducible quadratic factors. Those cases require different strategies, but they fall outside the scope of this specific subsubtopic. Here, the focus remains on linear-denominator terms that produce logarithmic results with no further algebraic manipulation needed once decomposition is complete.

When a decomposed term has the form A/(x − a) with A constant, its antiderivative is A ln|x − a| + C, so each such term contributes a logarithmic piece to the final result.

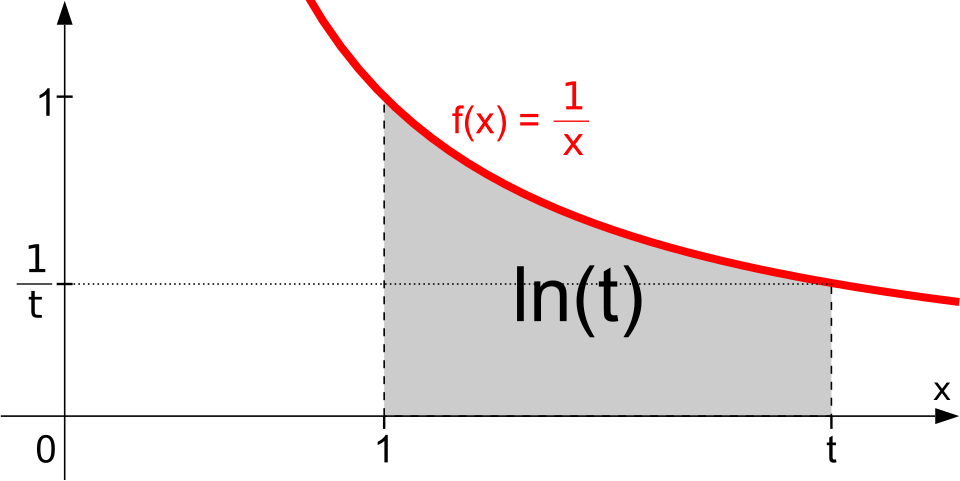

Graph of with the area from to shaded to represent . This illustrates the foundational relationship , which underlies the logarithmic antiderivatives produced by partial fraction terms of the form . The figure does not depict horizontal shifts such as , but these can be understood as translated versions of the same curve. Source.

Combining Multiple Decomposed Terms

A typical rational function may decompose into several components, each belonging to a recognizable antiderivative category. When integrating such expressions, students handle each piece sequentially and accumulate the results. This step highlights how decomposition converts a difficult integral into a structured list of familiar tasks.

To integrate each term effectively:

Recognize whether the denominator is linear and ensures the form .

Factor out constants whenever possible to match standard antidifferentiation patterns.

Apply the logarithmic rule precisely, including absolute value signs around the linear expression.

Keep the constant of integration outside the summation of individual antiderivatives.

This systematic breakdown allows complex expressions to be approached with confidence. Because AP Calculus emphasizes concept-driven manipulation, students should understand not only how to perform the integration but also why decomposition leads to simpler structures.

Importance of Logarithmic Antiderivatives

The appearance of logarithms is not incidental. When integrating decomposed rational functions, the logarithm emerges from the chain-rule relationship between the linear denominator and its constant derivative. This connection explains why antiderivatives of these terms follow a predictable and repeatable pattern.

Natural Logarithm: The logarithm with base , written , representing the inverse of the exponential function .

Because partial fractions often produce terms where the denominator’s derivative is a constant, the natural logarithm becomes the primary result of integrating those components. This reinforces the role of as a cornerstone of antiderivatives in rational-function contexts.

Understanding why the natural logarithm appears helps students avoid relying solely on memorized patterns and instead builds conceptual fluency. This skill is valuable not only for AP examinations but also for future mathematics coursework.

Structural Considerations in Integration

When integrating decomposed terms, attention to structure ensures mathematical accuracy. Students should be attentive to the coefficients in the denominator, correctly adjusting for scaling factors. They should also recognize when rewriting is beneficial before integrating, such as factoring out constants or identifying opportunities to simplify expressions.

Key structural habits include:

Always checking for a constant multiple inside the logarithm.

Writing absolute values around linear expressions inside logarithmic antiderivatives.

Keeping track of all constants so that no scalar adjustments are overlooked.

Viewing each decomposed term as an independent integration task guided by standard formulas.

This disciplined approach ensures that all integrals of decomposed rational functions with linear denominators follow clear, consistent rules aligned with the AP Calculus AB curriculum.

FAQ

A decomposed term will produce a logarithmic antiderivative whenever the denominator is a linear expression and the numerator is a constant.

This is because the derivative of a linear expression is itself a constant, matching the numerator needed for the standard log form.

If the numerator is anything other than a constant, the term must be simplified or adjusted before it can follow this pattern.

Students frequently forget to divide by the coefficient of x in the denominator.

Another common slip is omitting the absolute value in the logarithm, which is required for domain correctness.

Occasionally, students also combine multiple logarithmic terms too early, which can obscure sign errors.

Absolute values ensure the expression is defined for all x-values allowed by the original rational function.

Without absolute values, any negative input to a logarithm would be undefined.

They also preserve the behaviour of the antiderivative across intervals where the expression inside the log changes sign.

The order does not affect the final answer because integration is linear.

However, tackling simpler terms first can help reduce algebraic clutter.

Working through terms in a consistent left-to-right manner also helps reduce the likelihood of sign errors when combining logarithms.

Differentiate the final expression and verify that it returns the original decomposed form.

Check especially that:

• Coefficients inside logarithms are handled correctly.

• All constants and signs match the decomposed expression.

• No domain restrictions have been accidentally altered.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The function f is given by

f(x) = 6 / (x - 4).

Find an antiderivative F of f.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for recognising that the antiderivative of 1 / (x - 4) is ln|x - 4|.

• 1 mark for multiplying by the constant 6.

• 1 mark for including the constant of integration C.

Correct answer: F(x) = 6 ln|x - 4| + C.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A rational function g has already been decomposed into partial fractions as follows:

g(x) = 3 / (x + 2) − 5 / (2x − 1).

(a) Find the indefinite integral of g(x).

(b) Hence evaluate the definite integral of g(x) from x = 0 to x = 3.

(c) State one reason why partial fraction decomposition is helpful in integrating rational functions.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark for integrating 3 / (x + 2) to obtain 3 ln|x + 2|.

• 1 mark for integrating −5 / (2x − 1) to obtain −(5/2) ln|2x − 1|.

• 1 mark for including the constant of integration C.

Answer: ∫ g(x) dx = 3 ln|x + 2| − (5/2) ln|2x − 1| + C.

(b)

• 1 mark for substituting upper and lower limits correctly.

• 1 mark for calculating the expression at x = 3 accurately.

• 1 mark for calculating the expression at x = 0 accurately.

• 1 mark for obtaining the correct difference.

Final value: 3 ln 5 − (5/2) ln 5 − [3 ln 2 − (5/2) ln 1].

This simplifies to (1/2) ln 5 − 3 ln 2. (Equivalent simplified forms accepted.)

(c)

• 1 mark for a correct conceptual statement.

Acceptable answers include:

– It rewrites a complex rational expression as simpler fractions whose antiderivatives are standard.

– It allows separate integration of each simpler term.

– It converts difficult rational integrals into combinations of logarithmic forms.