AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use linear partial fraction decompositions to evaluate definite integrals of rational functions, combining the results of the simpler component integrals.’

Accumulating areas of rational functions often requires breaking complex expressions into simpler components. Applying partial fractions to definite integrals streamlines evaluation by transforming difficult integrands into manageable, integrable pieces.

Applying Partial Fractions to Definite Integrals

When a definite integral involves a rational function—a ratio of polynomials—it may be simplified by rewriting the integrand using a partial fraction decomposition, which expresses the function as a sum of simpler fractions with easier antiderivatives.

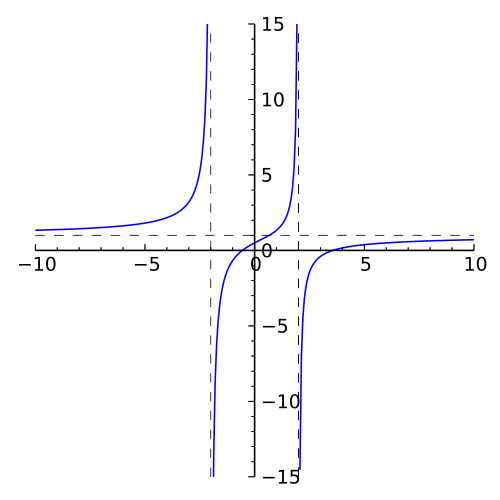

Graph of the rational function , illustrating a typical rational integrand suitable for partial fraction decomposition. Vertical and horizontal asymptotes depict its structure clearly. The specific formula exceeds syllabus requirements and serves only as a representative example. Source.

Since the AP syllabus explicitly emphasizes “use linear partial fraction decompositions to evaluate definite integrals,” this topic focuses on integrals whose denominators factor into nonrepeating linear factors. After decomposition, each resulting term can be integrated using previously learned antiderivative rules, often involving logarithmic expressions.

Because the decomposition process is performed before integration, applying partial fractions to definite integrals requires attention to the interval, the evaluation of antiderivatives at the integral bounds, and the proper combination of results from the simpler component integrals.

When Partial Fractions Are Appropriate

A rational integrand is a strong candidate for partial fractions when:

The denominator factors into linear components.

The degree of the numerator is lower than the degree of the denominator.

The resulting decomposed fractions match basic integration forms, such as .

If the numerator’s degree is too large, algebraic techniques such as polynomial long division should be applied first; however, this falls under a separate subtopic. Here, we assume the integrand is already prepared for decomposition.

Structure of Linear Partial Fractions

To apply partial fractions, a student rewrites a rational function with factorable denominator into a sum of fractions whose denominators contain the linear factors individually. These simpler fractions are then integrated over the original interval.

Partial Fraction Decomposition: A method of expressing a rational function as a sum of simpler rational expressions whose denominators are typically linear or otherwise easily integrable.

Because decomposition is an algebraic step, it occurs before engaging with definite integral bounds. Once decomposed, each term is integrated using standard techniques.

A variable expression split into partial fractions may produce terms of the form , each of which integrates to a logarithmic expression. These results must then be evaluated using definite integral bounds in accordance with the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC).

Integrating Decomposed Rational Functions

The AP syllabus specifies that students should “combine the results of the simpler component integrals.” This requires a clear, organized approach:

Process for Applying Partial Fractions to Definite Integrals

Factor the denominator into linear components to confirm the integrand is suitable for decomposition.

Set up the decomposition by assigning constants to each linear factor’s numerator.

Solve for the constants using algebraic methods such as substitution or comparison of coefficients.

Rewrite the integrand as a sum of simpler fractions.

Integrate each term individually using known antiderivative formulas.

Apply the limits of integration to each antiderivative carefully.

Combine the numerical results to obtain the final value of the definite integral.

Between decomposition and evaluation, students must preserve the original bounds.

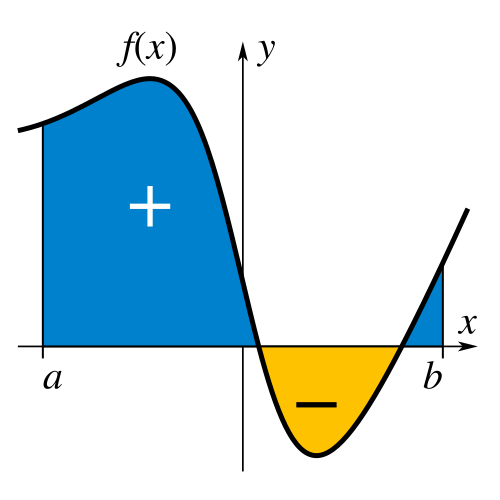

Diagram showing the definite integral as the signed area between a curve and the -axis on the interval from to . The shading illustrates positive and negative contributions to accumulated area. The specific function exceeds syllabus requirements and is included solely to visualize definite integral evaluation after decomposition. Source.

This is essential because, unlike substitution-based integrals, partial fractions typically do not require changing the variable of integration; therefore, no re-expression of bounds is needed.

Integrals of Linear Denominators

Many decomposed terms lead directly to logarithmic antiderivatives, which AP students should recognize from basic integration rules.

= independent variable

= constant determining horizontal shift of the denominator

These logarithmic relationships allow each fraction from the decomposition to be integrated smoothly. Students then apply the definite bounds to the resulting expression.

A decomposed rational function might also contain constant multiples of these forms. Because definite integrals respect linearity, constants may be factored out before evaluation.

Linearity and Definite Integrals in Partial Fractions

The linearity of definite integrals ensures that each partial fraction term contributes independently to the overall accumulated value. This property makes partial fractions especially effective in the definite integral context, since:

The integral of a sum equals the sum of the integrals.

A constant multiple may be pulled outside the integral symbol.

Each term may be evaluated across the bounds without interacting with other terms.

Together, these properties allow students to break a complicated rational integral into multiple simpler evaluations. By applying the FTC to each antiderivative, students obtain numerical values representing accumulated change over the interval.

Combining Component Integrals

Once each integral has been evaluated individually, the final step is simply to add the results. If any integrand in the decomposition produces a negative value over part of the interval, that value contributes negatively to the final sum, aligning with the geometric interpretation of definite integrals as signed area.

Thus, applying partial fractions to definite integrals transforms the problem from integrating one complex expression into integrating several much simpler ones. This aligns precisely with the AP objective: to “use linear partial fraction decompositions to evaluate definite integrals of rational functions, combining the results of the simpler component integrals.”

FAQ

Check the structure of the integrand. Partial fractions are preferred when the denominator factors into distinct linear terms and the numerator is of lower degree.

If substitution or a simple antiderivative rule does not immediately simplify the integrand, partial fractions typically offer the most direct path.

Yes. Partial fraction decomposition is purely algebraic and does not depend on the sign of the interval.

You simply evaluate the antiderivatives at the given bounds. However, be careful when expressions inside logarithms become negative; use absolute values when interpreting the final expression.

Typical errors include:

• Forgetting to apply bounds to each antiderivative term.

• Dropping negative signs when substituting limits.

• Forgetting to combine all evaluated terms at the end.

• Using incorrect constants from an earlier algebraic step.

No. The order does not affect the result. Each term is integrated independently and contributes additively to the final value.

Some students rearrange the terms to simplify arithmetic or to match known antiderivative forms more clearly, which is perfectly acceptable.

Each component typically has the form constant divided by (x minus a), whose antiderivative is a logarithmic expression. Therefore, once decomposed, logarithms arise naturally.

This makes partial fractions especially useful for definite integrals where logarithmic evaluation provides a straightforward numerical result after applying the limits.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The function f is a rational function defined on the interval [1, 4]. Its denominator factors as (x − 1)(x + 2).

(a) Explain why the definite integral from 1 to 4 of f(x) dx can be evaluated using linear partial fractions.

(b) State the form of the partial fraction decomposition of f(x), but do not determine the constants.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

• States that the denominator factors into non-repeating linear factors, allowing linear partial fractions.

(b) 1–2 marks

• Writes the correct form A divided by (x − 1) plus B divided by (x + 2). (1 mark)

• Notes that constants A and B would be determined algebraically, but are not required here. (1 mark)

Total: 2–3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the definite integral from 0 to 3 of (5x + 4) divided by (x + 1)(x + 2) dx.

(a) Write the integrand as a partial fraction decomposition of the form A divided by (x + 1) plus B divided by (x + 2).

(b) Determine the values of A and B.

(c) Hence evaluate the definite integral, showing all necessary steps in your working.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark

• Correctly expresses the decomposition as A divided by (x + 1) plus B divided by (x + 2).

(b) 2 marks

• Correctly sets up an equation to find A and B by comparing coefficients or substitution. (1 mark)

• Obtains correct values A = 1 and B = 4. (1 mark)

(c) 2–3 marks

• Integrates each term correctly using basic antiderivative rules for rational functions. (1 mark)

• Applies limits from 0 to 3 accurately. (1–2 marks depending on correctness and clarity)

Total: 5–6 marks