AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize integrands that can be simplified by algebraic techniques, such as factoring, long division, or completing the square, before integrating.’

Deciding when algebraic rearrangements simplify integration demands recognizing structural patterns in integrands, enabling efficient use of known antiderivative rules and ensuring expressions are rewritten into more integrable forms.

Purpose of Algebraic Rearrangement in Antidifferentiation

Before applying more advanced integration techniques, it is often essential to analyze whether an integrand becomes simpler through algebraic manipulation. These rearrangements allow you to convert challenging expressions into forms where basic antiderivative rules, substitution, or other techniques apply more naturally. Algebraic restructuring does not change the integral’s value; it only reorganizes the expression to reveal a more accessible path to integration.

Recognizing When Rearrangement Is Necessary

Students should identify characteristics signaling that an integrand is more complicated than it first appears. Common indicators include:

• A rational expression whose numerator and denominator have similar or mismatched degrees

• A quadratic expression not easily factorable in its original form

• An expression mixing polynomial and radical components

• A product or quotient that obscures recognizable derivative pairs essential for substitution

These clues suggest that reformatting the integrand will reveal underlying relationships between terms, allowing the integral to match known antiderivative patterns.

Factoring as a Rearrangement Strategy

Factoring reorganizes expressions to expose simpler multiplicative structures. It can reveal cancellation opportunities, derivative relationships, or substitution pathways hidden within the original form.

Factoring: Rewriting an expression as a product of simpler expressions whose multiplication reproduces the original expression.

Factoring is particularly useful when a complicated polynomial or mixed expression hides a common factor. Once factored, the integrand may simplify directly or allow substitution to become more evident. Recognizing perfect squares or special products can also transform seemingly complex expressions into forms appropriate for integration.

Identifying patterns such as difference of squares, factoring out a greatest common factor, or factoring quadratics can dramatically change the integration pathway.

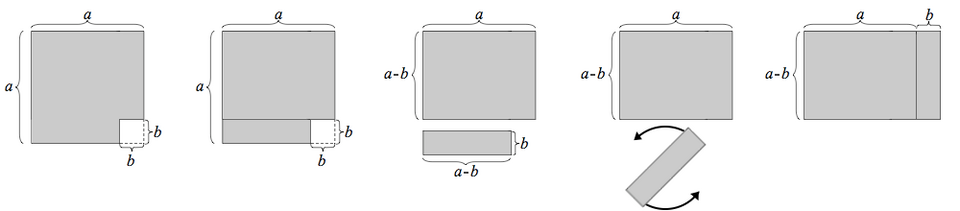

This geometric diagram represents as the difference in area between two squares and rearranges the pieces to form a rectangle of area . It visually justifies the factoring rule, helping reveal when a difference-of-squares pattern can simplify an integrand prior to integration. The figure focuses on the algebraic identity itself and does not depict integrals directly. Source.

Using Algebraic Long Division Before Integrating

When a rational function has a numerator whose degree is greater than or equal to the denominator’s degree, the integrand cannot be integrated efficiently until the expression is rewritten using polynomial long division. This method produces a combination of a polynomial and a proper rational function, each of which tends to have straightforward antiderivatives.

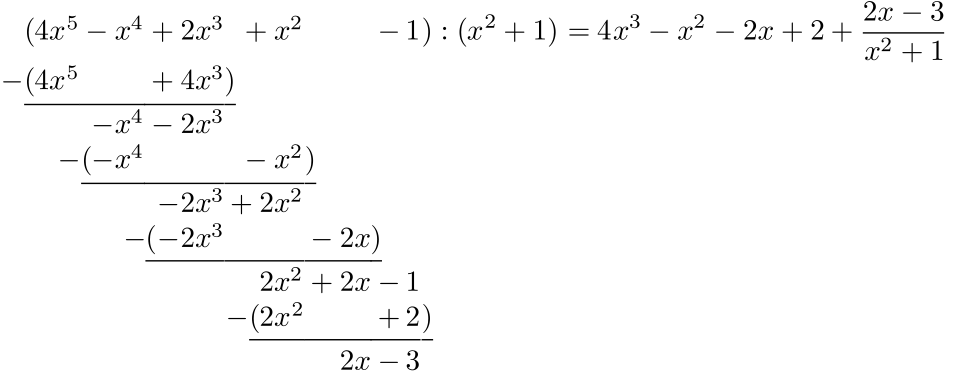

This diagram illustrates polynomial long division step by step, separating a complex rational expression into a quotient and a remainder term. It highlights how reorganizing the algebra prepares each component for simpler integration. The specific polynomials shown are examples and not required by the AP Calculus AB syllabus. Source.

Proper Rational Function: A rational expression in which the degree of the numerator is strictly less than the degree of the denominator.

Once rewritten, the polynomial component is easily integrated using power rules, while the remaining rational terms may require additional techniques such as substitution or partial fractions.

Why Division Often Precedes Other Techniques

Long division is not merely an organizational step; it is a foundational trigger enabling subsequent strategies. Many rational expressions appear resistant to substitution or factorization until division is performed. A divided form can also reveal hidden structures such as logarithmic or arctangent derivatives that were not previously apparent.

Completing the Square to Simplify Integrands

Completing the square rewrites a quadratic expression inside an integrand into a structured, shifted-square form that aligns with known integral formulas involving logarithmic or inverse trigonometric functions. This strategy is particularly valuable when the quadratic appears inside rational or radical expressions.

Completing the Square: Transforming a quadratic expression into an equivalent form by adding and subtracting terms to create a perfect square trinomial.

After completing the square, the form of the integrand typically suggests which antiderivative rule applies.

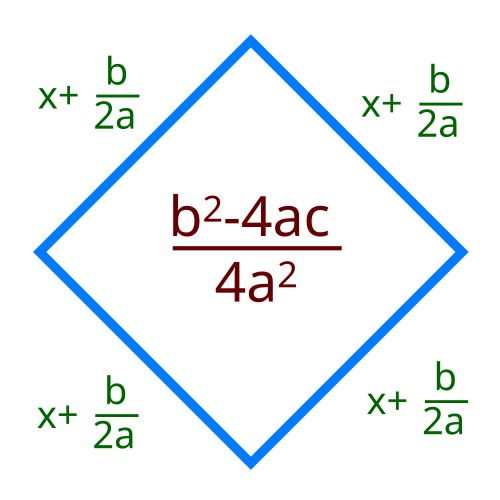

This diagram shows how completing the square rewrites a general quadratic expression into the structured form , revealing patterns useful for integration. It demonstrates how algebraic rearrangement exposes forms associated with standard antiderivative rules. The final derivation of the quadratic formula includes extra content beyond the AP Calculus AB requirement. Source.

A sentence is necessary here to maintain proper spacing before any additional equation content.

= Variable of integration

= Constants that reposition and vertically shift the parabola

Deciding Which Rearrangement Technique to Use

Because integrands vary widely, selecting the appropriate algebraic method requires analytical judgment. Students should examine:

• The relative degrees of numerator and denominator in rational functions

• Whether a quadratic expression is factorable or better suited to completing the square

• Whether terms share a common factor that simplifies the structure

• Whether rearrangement exposes substitution opportunities or prepares the integrand for partial fractions

This decision-making process helps prevent unnecessary work and ensures the chosen integration method aligns with the integrand’s underlying algebraic structure.

Building Intuition Through Structural Awareness

Developing proficiency in identifying when to use factoring, long division, or completing the square relies on recognizing algebraic patterns across many integration contexts. Observing how rearrangements transform unwieldy forms into structured expressions is a critical step toward mastery. Integrands often disguise their simplest form, and algebraic rearrangement is the tool that reveals the path toward successful antidifferentiation.

FAQ

Look for algebraic patterns that immediately reduce complexity. For example, if the numerator of a rational expression shares a common factor with the denominator, cancellation may occur after factoring.

Patterns such as perfect squares, difference of squares, or a common monomial factor often indicate that factoring will convert the integrand into a form suited to straightforward rules or substitution.

Completing the square is particularly useful when the quadratic does not factor neatly into real linear factors. This often occurs when its discriminant is negative or unfriendly for simple mental factorisation.

By rewriting the quadratic into a shifted-square form, you expose a structure that aligns with known integral types, especially those involving inverse trigonometric functions or substitutions of the form u = x + constant.

Long division separates the integrand into simpler parts with clearer antiderivative patterns. The resulting polynomial term is straightforward to integrate, while the remaining rational part is easier to classify and manipulate.

Rearrangement through division also prevents errors by reducing clutter and isolating the term that requires more attention, rather than integrating the original expression in one complicated step.

Yes. Simplifying the integrand often reveals a substitution that would have been difficult or impossible to spot in the original form.

For example, completing the square may uncover a natural shift substitution, while factoring might isolate a pair of terms that match a derivative pattern. Rearrangement frequently narrows the list of viable substitutions to a single obvious choice.

Typical errors include:

• Completing the square incorrectly by mishandling constant terms

• Factoring only part of an expression, leaving hidden structure unrecognised

• Neglecting to perform long division when it is required, leading to improper use of advanced techniques

• Attempting substitution too early, before rewriting the integrand into a clearer form

Careful checking of algebraic steps reduces these errors substantially.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The integrand (3x² + 5x + 2) / (x + 1) is to be integrated.

Explain why an algebraic rearrangement should be carried out before attempting to find the antiderivative, and state the specific technique that should be used.

Question 1

• Identifies that the degree of the numerator is greater than or equal to the degree of the denominator (1 mark).

• States that polynomial long division should be used (1 mark).

• Gives a valid reason, such as: the rearrangement produces a polynomial plus a proper rational function that is easier to integrate (1 mark).

Total: 1–3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the integral of (4x + 7) / (x² + 4x + 5).

(a) Explain why completing the square is a useful algebraic rearrangement for this integrand.

(b) Rewrite the denominator by completing the square.

(c) State how the rewritten form helps determine which integration method or formula becomes applicable, without carrying out the actual integration.

Question 2

(a)

• States that the quadratic in the denominator is not factorable into simple linear factors, making completing the square appropriate (1 mark).

• Notes that rewriting the quadratic in square form makes the structure of the integrand more recognisable for standard integration techniques (1 mark).

(b)

• Correctly rewrites x² + 4x + 5 as (x + 2)² + 1 (2 marks).

Award 1 mark if the method is correct but the final constant is incorrect.

Award 2 marks only for the fully correct completed square.

(c)

• States that the rewritten form resembles a standard expression leading to an inverse trigonometric or substitution-based integral (1 mark).

• Clearly explains that the simplified structure guides the choice of integration method (1 mark).

Total: 4–6 marks.