AP Syllabus focus:

‘Differential equations relate an unknown function of an independent variable to one or more of its derivatives, allowing us to describe how a quantity changes and to develop mathematical models of real situations.’

Understanding differential equations is essential for modeling dynamic processes, because these equations express how a quantity changes rather than just what its value is at a moment in time.

What a Differential Equation Represents

A differential equation is an equation that involves an unknown function and one or more of its derivatives.

Differential Equation: An equation relating an unknown function to one or more of its derivatives in order to describe how that function changes.

This relationship allows us to represent real-world change mathematically. Instead of giving a direct formula for a quantity, a differential equation describes the rate of change, which captures how the quantity evolves with respect to an independent variable.

A normal sentence here ensures definitions are not consecutive. Differential equations appear in science, economics, and engineering because many natural phenomena are governed by how rapidly something grows, decays, or varies.

Components of a Differential Equation

Understanding the structure of a differential equation requires recognizing the unknown function, the independent variable, and the derivative expression that connects them.

The Unknown Function

The unknown function is the quantity whose behavior we are trying to understand. It is usually written as , , , or another variable depending on the context.

The Independent Variable

The independent variable is the quantity with respect to which change is measured. It might represent time, position, or another contextual quantity.

Independent Variable: The variable with respect to which the derivative is taken; it represents the input or driving parameter of change.

A normal sentence appears here before the next definition.

Dependent Variable: The output quantity whose value depends on the independent variable and whose rate of change is described by the differential equation.

The dependent variable “depends on” the independent one, and its rate of change can reveal significant information about the underlying behavior of a system.

Why Differential Equations Are Useful for Modeling

Differential equations model change, making them powerful tools in situations where values do not remain constant. They allow us to:

Represent how populations grow or decline.

Track motion, velocity, or acceleration.

Describe chemical reactions or cooling processes.

Model financial growth or decay scenarios.

In all these cases, the defining feature is that the rate of change depends on the current value of the quantity or other variables.

Relating Rates of Change to Real Situations

A differential equation provides a rule for how the dependent variable changes. For example, describing a quantity’s rate of change with respect to time may give insight into whether its growth accelerates, slows, or stabilizes.

= The derivative of with respect to ; the instantaneous rate of change

= Independent variable

= Dependent variable representing the unknown function

A normal sentence follows to maintain required spacing. The equation above expresses that the slope of the solution curve at any point depends on both the value of and the value of . This is typical when modeling natural processes where multiple factors influence how a quantity changes.

Local Behavior and Global Behavior

The derivative reveals local behavior — how the function acts at a particular point — while the entire differential equation helps us understand the global behavior of solutions over an interval.

Key ideas include:

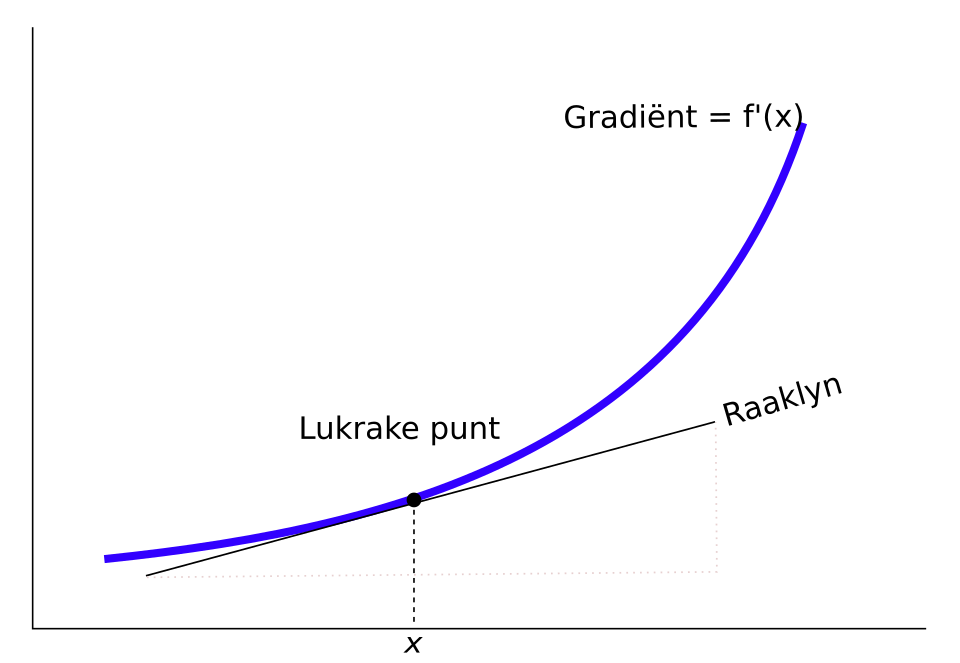

The derivative gives the tangent slope at each point.

This diagram shows a curve with a tangent line at a single point, illustrating that the derivative represents the slope of the tangent. It visually links geometric slope to rate-of-change concepts foundational to differential equations. Some additional geometric labels appear but simply enrich the interpretation without exceeding AP expectations. Source.

A differential equation controls how the slope changes from point to point.

Solutions emerge by following these slopes across the domain.

Modeling Real Situations with Differential Equations

The syllabus emphasizes that differential equations allow us to develop mathematical models grounded in context. To use them meaningfully, students must be able to interpret how a described situation translates into a relationship involving derivatives.

Common contexts include:

Motion along a straight line, where acceleration depends on velocity or position.

This figure depicts a baseball falling under gravity, with the downward acceleration labeled . It emphasizes how motion can be modeled by relating acceleration, velocity, and position through differential equations. Although it introduces a second-order setting, it cleanly illustrates how physical change motivates differential-equation modeling. Source.

Population dynamics, where the growth rate depends on population size.

Cooling processes, where temperature change depends on the difference between an object and its environment.

In each case, the differential equation simplifies complex behavior into a focused statement about change.

A differential equation therefore serves two major purposes in modeling:

It encodes a principle or assumption about how a system behaves, such as “the rate of change is proportional to the current value.”

It provides a framework from which solutions can be found, analyzed, or approximated.

By understanding differential equations, students gain access to mathematical tools that express not just what happens, but how and why it happens through the language of change.

FAQ

Differential equations describe how a quantity changes rather than giving its explicit formula. Ordinary functions give the value directly, while differential equations specify the rule governing its behaviour.

This means differential equations are especially useful when the exact form of the function is unknown, but the relationship between the function and its rate of change is understood.

Rates express how a system responds at each moment, which reflects real-world behaviour more accurately than static values.

By focusing on rates, we capture dynamic interactions such as growth, decay, and motion without needing a fully determined formula at the outset.

Yes. Some descriptions are ambiguous or can be interpreted in different mathematical forms.

For example:

• A phrase like “changes in proportion to its value” always implies proportionality, but the constant of proportionality may be positive or negative depending on context.

• Additional information may be required to identify the correct sign or structure.

In real-world scenarios, the natural choice is not always obvious. Time is often, but not always, the independent variable.

Situations involving spatial change, temperature change, or economic inputs may require thoughtful interpretation to determine which quantity drives the variation of the other.

Understanding what a differential equation expresses conceptually prepares students to interpret solutions later.

This early exposure emphasises that differential equations encode relationships between quantities, and that solving them is one step that follows from first understanding the system’s underlying structure.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A quantity y changes with respect to time t. A verbal description states:

"The rate of change of y is equal to three times the current value of y."

(a) Identify the dependent and independent variables.

(b) Write a differential equation that models this situation.

Question 1

(a)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies y as the dependent variable and t as the independent variable.

(b)

• 1 mark: Writes the correct differential equation dy/dt = 3y.

• 1 mark: Uses correct notation and structure (credit if equivalent wording such as "rate of change of y equals 3y").

Total: 2–3 marks depending on precision.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A tank contains a chemical solution. The verbal description below is given:

"The amount of chemical A in the tank decreases at a rate proportional to the amount present at time t. The rate of decrease is twice the amount present."

(a) State the dependent and independent variables.

(b) Explain in words what the phrase 'rate proportional to the amount present' means in this context.

(c) Write a differential equation that represents this situation.

(d) Briefly describe what information this differential equation gives about how the amount of chemical changes over time.

Question 2

(a)

• 1 mark: Identifies the dependent variable as the amount of chemical A (y).

• 1 mark: Identifies the independent variable as time t.

(b)

• 1 mark: States that the rate of change depends directly on the current amount; as the amount changes, the rate changes proportionally.

(c)

• 1 mark: Writes the differential equation dy/dt = -2y (negative sign required for decrease).

(d)

• 1–2 marks: Explains that the equation describes how quickly the amount decreases, showing that larger amounts decrease faster and the rate slows as the tank empties.

Total: 4–6 marks depending on detail.