AP Syllabus focus:

‘Volumes around lines like y = k or x = c are still found using V = ∫ π(radius)², where the radius is the difference between the function and the chosen axis.’

When using the disc method for solids of revolution about shifted horizontal or vertical lines, students express radius as a distance to the new axis before constructing an appropriate definite integral.

Writing Disc Method Integrals for Shifted Axes

Understanding Solids of Revolution with Shifted Axes

When a region in the plane is revolved around a line such as or , the resulting figure is a solid of revolution, whose volume is computed by accumulating circular cross sections perpendicular to the chosen variable. These circular slices are known as discs, each having an area determined by its radius.

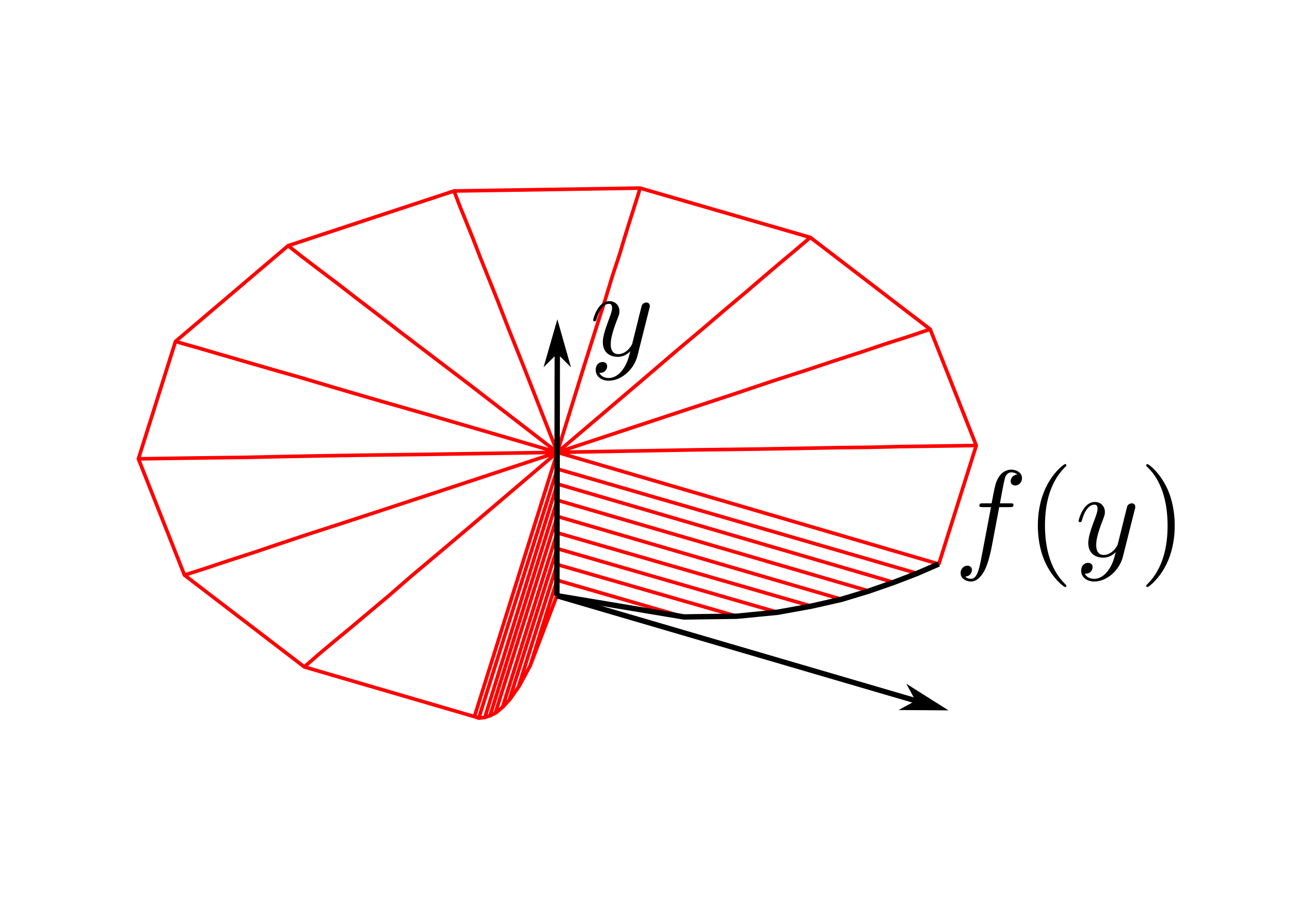

Illustration of the disc method for a solid of revolution, using the curve and a circular cross-section. The diagram emphasizes the radius as the distance from the curve to the axis of revolution and the infinitesimal slice thickness used in integration. The specific function shown exceeds syllabus detail but models the same geometric principles. Source.

The Role of the Radius in Disc Method Integrals

The radius of a disc is the perpendicular distance from a point on the generating function to the axis of revolution.

Radius: The perpendicular distance between the curve defining the boundary of a region and the axis about which the region is revolved.

This distance must always be nonnegative and expressed in terms of the variable of integration.

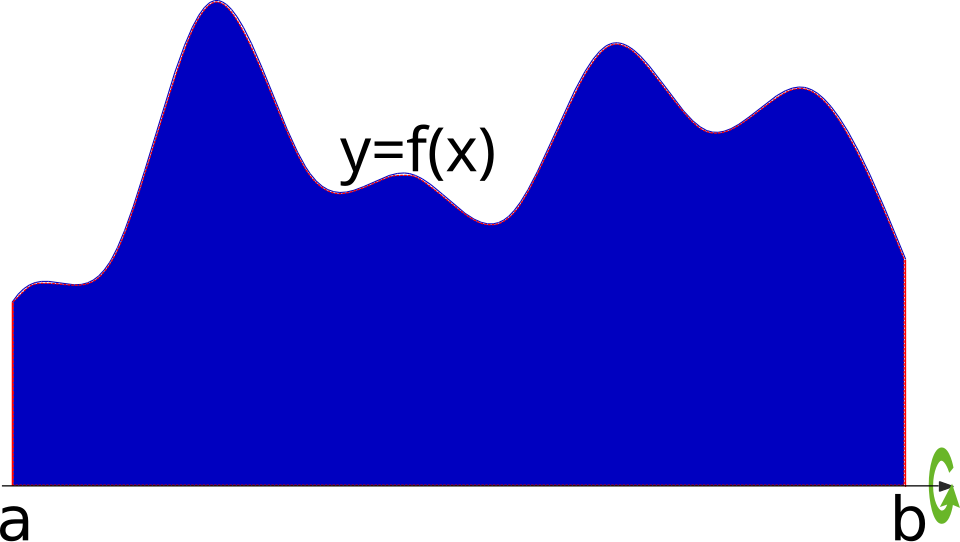

A region in the plane that forms a solid of revolution when rotated around a horizontal axis. The image highlights the graph, the bounded region, and the rotation arrow, demonstrating how the radius in a disc-method integral represents vertical distance to the axis. Some visual details exceed AP AB scope but reinforce the geometric interpretation. Source.

An integral using the disc method requires expressing volume as the accumulated area of circular cross sections.

= Volume of the solid (cubic units)

= Distance from curve to axis of revolution (units)

Before applying this relationship, the integrand must be rewritten to reflect the shifted axis. A correctly structured volume integral will always match the orientation of the slices and the limits of integration with the geometry of the region.

A sentence must appear between any two equation or definition blocks, so this text ensures proper spacing while reinforcing that understanding structure precedes symbolic computation.

Determining the Radius for Horizontal Lines of Revolution

When revolving around , the radius is measured vertically. Students must compare the function value with the axis value , keeping the radius expression positive. Common structures include:

If the function lies above the axis, radius = .

If the function lies below the axis, radius = .

If the region crosses the line, radius must be expressed piecewise, though AP Calculus AB problems typically avoid piecewise expressions in disc-only contexts.

Important considerations when identifying radius for horizontal axes include:

Ensuring the vertical direction matches the chosen integration variable.

Confirming that the integrand depends solely on when integrating with respect to .

Verifying that the axis does not require re-expressing the function.

Determining the Radius for Vertical Lines of Revolution

When revolving around , the radius is measured horizontally, requiring the boundary expressed as in terms of if the region is better described using vertical slices. In these cases, students determine radius using:

If the function lies to the right of the axis, radius = .

If the function lies to the left of the axis, radius = .

Students should be careful to choose the proper orientation of integration because integrating with respect to forces the radius to be written using expressions involving only. This may require rewriting the boundary function as .

Process for Writing Disc Method Integrals for Shifted Axes

To organize the construction of volume expressions, students can follow a consistent sequence:

Identify the axis of revolution, noting whether it is horizontal or vertical.

Determine the direction of slicing, matching discs perpendicular to the axis.

Express radius as distance to the axis, ensuring positivity and correct variable form.

Write the integral with , using the variable of integration corresponding to slice orientation.

Set the limits of integration by projecting the interval of the region onto the axis of the slicing direction.

Why Shifted Axes Change the Radius Expression

A shifted axis alters only the radius, not the general structure of the disc formula. The definite integral remains an accumulation of circular areas, but the radius must incorporate the horizontal or vertical offset. This perspective aligns with the syllabus requirement that, even for shifted lines of revolution, volumes are found using , with the radius written as a difference between the function and the chosen axis.

Visualizing the Geometry of Shifted Discs

Students benefit from picturing the disc as centered on the axis of revolution. The radius then becomes a direct measurement from the axis to the curve. This perspective clarifies why vertical distances correspond to horizontal lines of revolution and vice versa, connecting geometric intuition with algebraic formulation.

Common Structures for Radius Expressions

To reinforce pattern recognition, typical radius forms include:

when revolving around .

when revolving around .

Rewritten functions such as if integrating with respect to is more natural.

Recognizing these patterns ensures that students consistently form correct disc integrals, even when the axis of revolution is shifted away from the coordinate axes.

FAQ

A shifted axis does not by itself force a change in variable. The choice depends on the orientation of the slices.

If discs are perpendicular to the axis of revolution, integrate with respect to the variable corresponding to that direction.

Only switch variables if the region’s description becomes simpler when rewritten in terms of the other variable.

Students often measure distance to the wrong curve or misinterpret whether the function lies above, below, left, or right of the axis.

Useful checks include:

• Visualising the perpendicular segment from the curve to the axis

• Ensuring the radius remains positive on the entire interval

• Confirming the radius matches the chosen integration variable

Yes. Although absolute values represent distance, they can often be simplified by determining which quantity is larger on the interval.

If a curve always lies above a horizontal axis, or always to the right of a vertical axis, the sign of the expression is fixed.

Use interval reasoning to remove the absolute value and keep the formula simple.

The limits themselves usually stay the same unless the region is more naturally described in another variable.

A shift changes the radius expression, not the horizontal or vertical extent of the region.

You only adjust limits if you intentionally change the variable of integration and must describe the region in new coordinates.

A clear diagram can reveal geometric relationships that may be harder to see algebraically.

Look for:

• The relative position of the curve and shifted axis

• The direction of perpendicular slicing

• Whether the region crosses the axis

Accurate sketches help avoid sign errors and unnecessary complication in the radius expression.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A region in the plane is bounded above by the curve y = 4 - x and below by the x-axis. The region is revolved about the horizontal line y = –2 to form a solid of revolution.

Write down a definite integral using the disc method that represents the volume of the solid.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies that discs are perpendicular to the axis y = –2 and thus uses integration with respect to x.

• 1 mark: Correct radius stated as vertical distance from y = 4 – x to y = –2, i.e. (4 – x) – (–2) or equivalent.

• 1 mark: Correct volume integral of the form integral from x = 0 to x = 4 of pi(radius)^2 dx.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function f is defined on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 3 and is given by f(x) = 1 + x. The region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis, and the vertical lines x = 0 and x = 3 is revolved about the vertical line x = 5 to create a solid of revolution.

(a) Express the radius of a typical disc in terms of x.

(b) Write an integral expression for the volume of the solid using the disc method.

(c) Without evaluating the integral, briefly explain why the radius expression must remain positive on the interval.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Recognises radius is a horizontal distance to x = 5.

• 1 mark: Correct radius expression 5 – x.

(b)

• 1 mark: Correct use of the disc method, volume written as an integral with pi(radius)^2.

• 1 mark: Correct limits 0 to 3 and correct substitution of radius into the integrand.

(c)

• 1 mark: States that on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 3 the quantity 5 – x is always positive, ensuring the radius represents a valid distance.