AP Syllabus focus:

‘When revolving around a horizontal or vertical line other than an axis, students adjust the radius function to measure distance from the curve to the new axis of revolution.’

Revolving a region around a nonstandard horizontal or vertical line broadens the disc method by modifying radii to reflect distances from curves to shifted axes. This adjustment ensures correct volume measurement.

Revolving Regions Around Horizontal or Vertical Lines

When a plane region is revolved around a line that is neither the x-axis nor the y-axis, the resulting solid of revolution still consists of circular cross sections.

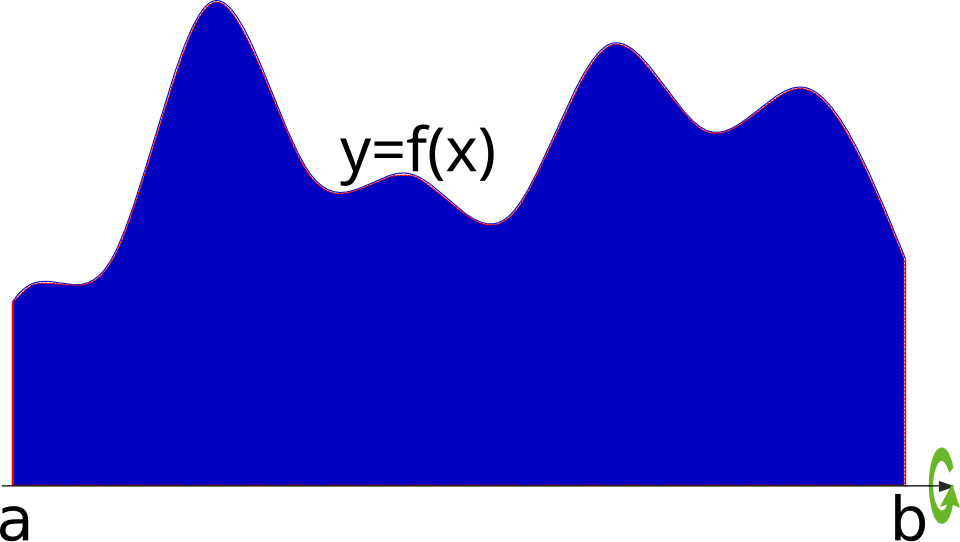

This figure illustrates a planar region and the horizontal axis about which it is rotated to generate a solid of revolution via the disk method. Each thin rectangle perpendicular to the axis creates a circular disk whose radius is the distance from the curve to the axis. The image includes a specific example curve not tied to the syllabus, but the key idea is the general construction of discs from a region and an axis. Source.

However, the radius of each circular slice is no longer simply the value of the function; instead, it must be computed as the distance between the curve and the chosen line of revolution. This subsubtopic emphasizes how to identify and construct these radius expressions accurately so that the resulting volume is correctly modeled using integration.

Understanding the Concept of a Shifted Axis

A shifted axis is any horizontal or vertical line other than the coordinate axes used as the center of rotation. Because the axis is displaced in the plane, the geometric structure of each disc changes accordingly. Students must focus on interpreting diagrams and functional relationships to determine appropriate radii.

Shifted Axis of Revolution: A vertical or horizontal line, not equal to the x- or y-axis, about which a region is rotated to produce a solid of revolution.

When the axis is shifted, the radius of each disc depends on the vertical or horizontal distance from the curve to that line. For vertical lines, radii are horizontal distances; for horizontal lines, radii are vertical distances. Thinking geometrically helps reinforce which orientation is appropriate.

Identifying the Radius for Horizontal Lines

A horizontal line has the form . When revolving around such a line, the radius at each point of the solid corresponds to a vertical distance.

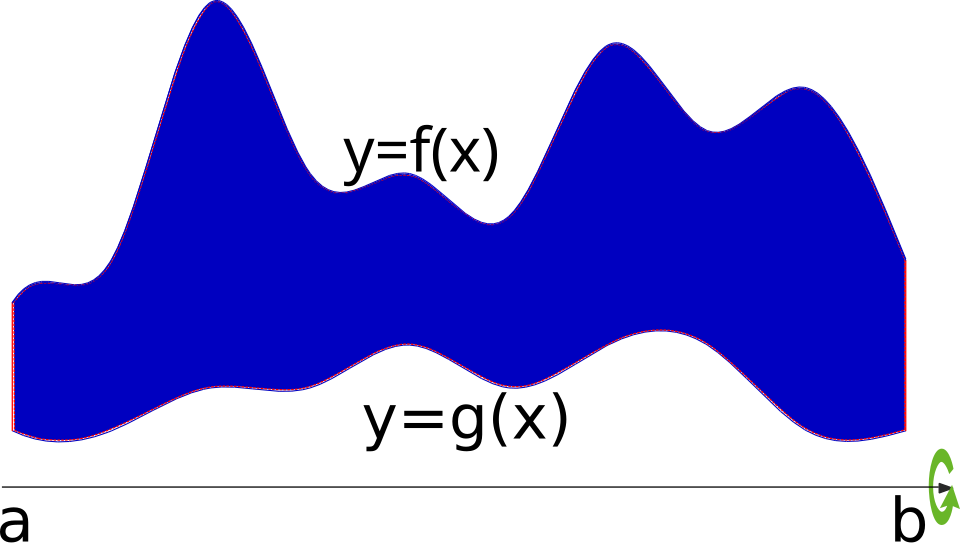

This figure shows a region between two functions being revolved around a horizontal axis, producing washer-shaped cross sections. The outer and inner radii are explicitly drawn as vertical segments from each curve down to the axis, emphasizing that radii are distances to the line of revolution. The presence of both inner and outer radii reflects the washer method, which is additional detail beyond the current focus but illustrates the same distance-from-axis principle. Source.

This distance is found by subtracting the y-value of the curve from the constant value or vice versa, depending on whether the curve lies above or below the line. The radius must always be expressed as a positive value that measures the perpendicular distance to the axis.

= function describing the boundary of the region

= constant defining the horizontal axis of revolution

Including the absolute value ensures the radius remains nonnegative, which aligns with the geometric meaning of a physical length. Although absolute value notation appears in the distance formula, algebraic simplification typically removes it because the relative positions of curves and axes are known from the graph.

A typical scenario involves revolving a region bounded above or below by a function. In these cases, the graph's orientation clarifies how to determine the sign of the distance.

Identifying the Radius for Vertical Lines

A vertical line has the form . Rotating around this axis requires measuring horizontal distances.

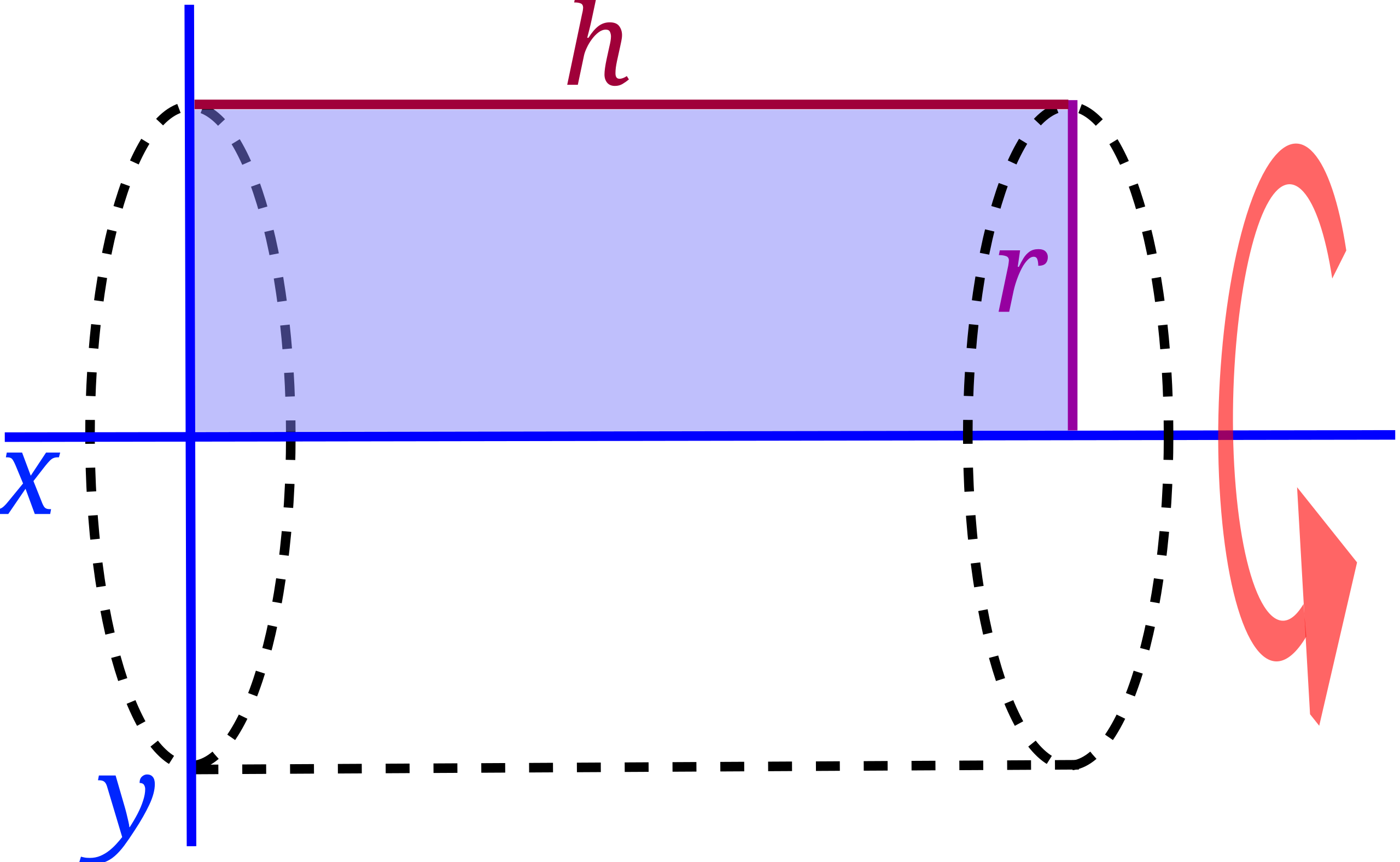

This diagram depicts a rectangle in the plane being rotated about a vertical line to form a right circular cylinder. The radius of the cylinder is the horizontal distance from the rectangle to the axis of revolution, illustrating how solids of revolution arise from revolving regions about vertical lines. The specific example focuses on a rectangle, which is simpler than a general function graph, but the underlying distance-to-axis idea is the same as in the notes. Source.

Functions may need to be rewritten as expressions for in terms of if the region is better described using a horizontal orientation for the discs.

The radius is established by computing how far a curve lies from the line . Issues arise when the region is bounded by more than one function, requiring careful consideration of which function forms the relevant side of the region relative to the axis of revolution.

= function expressing in terms of

= constant defining the vertical axis of revolution

This formulation ensures proper alignment with the geometric notion of radius as a perpendicular distance. When the disc method is used, rotating around a vertical line may require integrating with respect to if that produces a simpler single integral.

A clear sketch or mental model of the region often helps clarify the orientation and the necessary form of the radius.

Adapting the Disc Method to Shifted Axes

The disc method still applies when revolving around a horizontal or vertical line, but the formula for the radius changes to reflect the displacement of the axis. Since volume is computed by accumulating circular discs, the structure of the integral remains the same. Students must translate geometric distances into algebraic expressions that correctly capture the radius at each slice.

Identifying the interval of integration remains essential. The bounds are determined by the region’s projection onto the axis of integration, whether - or -oriented. Choosing the orientation that produces a single integral with consistent radii is often most efficient.

Key Considerations When Working with Shifted Axes

Determine whether the axis of revolution is horizontal or vertical, as this dictates whether distances are measured vertically or horizontally.

Express the radius in terms of distance from the curve to the shifted line, ensuring correct orientation and nonnegative values.

Choose the direction of integration based on whether the radius is naturally a function of or .

Confirm the region’s bounds by analyzing intersections or provided interval limits.

Maintain consistency in measuring distances across the entire interval to avoid incorrectly switching radius expressions.

Understanding these elements ensures that solids created by revolving regions around shifted lines are modeled precisely, using correct geometric distances and appropriately structured integrals.

FAQ

Determine whether the curve lies above or below the line on the interval of interest. The radius is always the positive vertical distance between the curve and the line.

If the curve crosses the line of revolution within the interval, split the region at the intersection point and define separate expressions to ensure the radius remains non-negative.

A horizontal line of revolution generally leads to radii expressed using vertical distances, best handled when the integrand is a function of x. A vertical line of revolution relies on horizontal distances, often more manageable using functions of y.

Rewriting prevents the need for multiple integrals and keeps the radius expression consistent across the chosen interval.

Typical mistakes include:

• Forgetting that the radius is a horizontal distance, not a vertical one.

• Using c − x instead of the positive distance |x − c|, which may reverse sign.

• Failing to check whether the region lies entirely to the left or right of the line.

A quick sketch usually eliminates these errors.

If the region touches the line of revolution, the cross sections form discs.

If the region does not touch the line, a gap appears between the region and the axis, creating washers instead.

The choice depends on the geometry of the rotated region, not the fact that the axis is shifted.

Sometimes. Introducing a temporary substitution such as u = x − c or u = y − k can simplify expressions for the radius by eliminating constant offsets.

This technique does not change the geometry of the solid but can make the integrand cleaner and reduce algebraic errors during integration.

Practice Questions

A region in the plane is bounded above by the curve y = 4 and below by the curve y = x. The region is revolved about the horizontal line y = 6.

Find an expression for the radius of a representative disc in terms of x.

(1–3 marks)

Mark Scheme

• Identifies radius as the vertical distance from y = 6 to the curve y = x. (1 mark)

• Correct radius: 6 − x. (1 mark)

Maximum: 2 marks.

The region enclosed by the curve y = 2x, the line x = 0, and the line x = 3 is revolved about the vertical line x = –1.

(a) Write an expression for the radius of a typical disc in terms of y.

(b) Express x as a function of y.

(c) Set up, but do not evaluate, a definite integral that represents the volume of the resulting solid.

(4–6 marks)

Mark Scheme

(a)

• Recognises radius is the horizontal distance from x = –1 to the boundary curve. (1 mark)

• Writes radius in terms of y: radius = x − (–1). (1 mark)

(b)

• Solves y = 2x for x: x = y/2. (1 mark)

(c)

• Identifies correct limits in terms of y (from y = 0 to y = 6). (1 mark)

• Sets up volume integral using discs: V = integral from 0 to 6 of pi[(radius)^2] dy. (1 mark)

• Substitutes radius = y/2 + 1 into the integrand. (1 mark)

Maximum: 6 marks.