AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students compare how changing the line of revolution affects the radius function, the corresponding definite integral, and the resulting volume of the solid of revolution.’

Changing the line around which a region is revolved alters the geometry of each disc, so understanding how shifted axes modify radii and integrals is essential for volume computation.

Comparing Lines of Revolution in the Disc Method

When using the disc method to find the volume of a solid of revolution, the shape is generated by revolving a region around a specified axis.

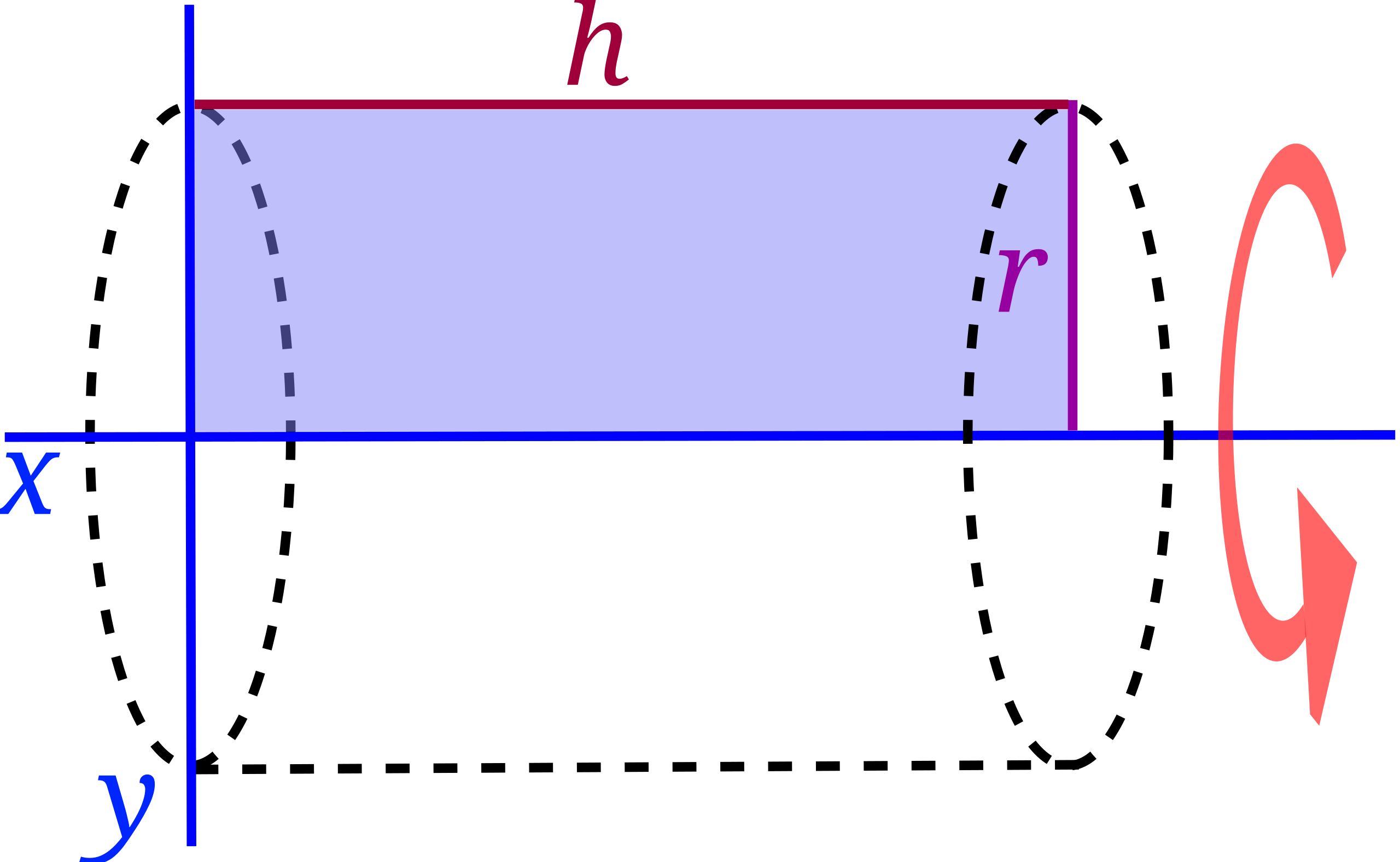

Solid of revolution formed by rotating a rectangle around a line to create a cylinder. The diagram highlights the axis of revolution and the circular cross sections that correspond to discs in the volume integral. The presence of multilingual labels is extra context and not required by the syllabus, but it does not affect the mathematical idea shown. Source.

The choice of this axis determines the distance from each point on the region to the axis of revolution, which in turn affects the radius function, the structure of the definite integral, and ultimately the volume of the solid. This subsubtopic focuses on how comparing different horizontal or vertical lines of revolution reveals the sensitivity of the volume to changes in radius.

When the axis is shifted away from a coordinate axis, students must adjust the radius expression accordingly. Because radius enters the integral as a squared quantity, even small variations in the axis location can produce large differences in volume, underscoring the importance of selecting the correct radius form for every disc.

Understanding the Radius Function Under Different Axes

How the Radius Changes

The radius function is the distance from the curve being revolved to the chosen axis of revolution. This distance changes depending on whether the axis is:

the x-axis,

the y-axis,

a horizontal line such as , or

a vertical line such as .

Radius Function: The distance from a point on the generating curve to the axis of revolution, used as the radius of each circular disc in the volume integral.

A shift in the axis modifies this distance by adding or subtracting constants, depending on the orientation. This shift transforms how the region expands or contracts when revolved.

Students compare lines of revolution by analyzing how each choice affects the shape and scale of the resulting solid. They interpret these changes by examining how the radius varies along the interval and how this variation influences the total accumulated volume.

Revisiting the Disc Method Structure

Why the Integral Changes

The disc method accumulates the volumes of infinitely thin circular slices whose areas depend directly on the square of the radius. Therefore, any modification to the radius function changes the integrand substantially. A shifted axis requires careful attention to the direction in which distance is computed.

= volume of the solid

= distance from the curve to the axis of revolution (units vary)

After adjusting the radius, students rewrite the integral so that it reflects the new dependence on or , depending on the problem’s orientation. They then compare how these integrals differ across axes.

A single region can produce several distinct solids when revolved around different lines.

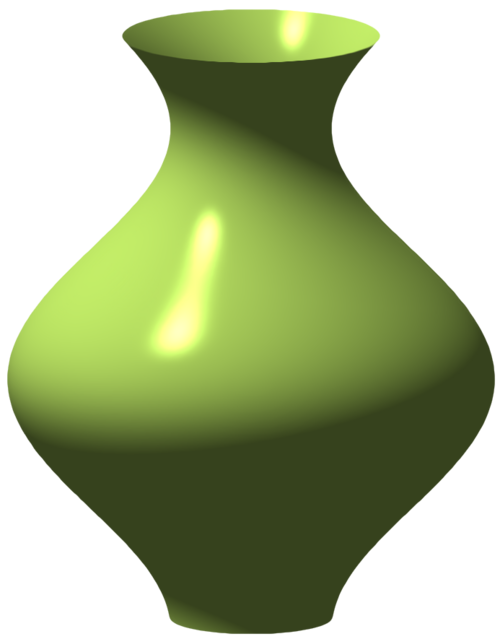

Illustration of a surface of revolution obtained by rotating a curve around an axis. The image emphasizes the continuous rotational symmetry of the resulting surface, helping students connect a generating curve to the 3D shape created by revolution. The detailed shading exceeds syllabus requirements but supports geometric intuition about how a solid’s shape depends on the chosen axis. Source.

By comparing these solids, students gain insight into spatial relationships and the role of relative distance.

Horizontal vs. Vertical Lines of Revolution

Shifts Parallel to the Axes

When revolving around horizontal lines, students measure vertical distance between the generating function and the axis. When revolving around vertical lines, they measure horizontal distance.

Important distinctions include:

A horizontal shift (e.g., revolving around ) affects the output values of the function, altering vertical radius measurements.

A vertical shift (e.g., revolving around ) affects the input values, requiring radii written in terms of horizontal distances.

Students compare lines of revolution by noting how the radius formula changes structure:

sometimes becoming an absolute difference,

sometimes requiring re-expression of a function in terms of or ,

sometimes switching the variable of integration for simplicity.

These comparisons highlight the mathematical flexibility needed to visualize and compute solids effectively.

How Changing the Axis Alters the Solid

Conceptual Effects on Volume

Changing the line of revolution transforms the solid in several key ways. Students should recognize the following comparative features:

Radius magnitude: A farther axis increases all radii, enlarging the solid.

Rate of radius change: The radius may grow or shrink more quickly depending on the axis location.

Integrand behavior: Because the radius is squared, small differences in distance can create significantly different volume outputs.

Symmetry: Revolving around certain lines may produce symmetric solids, while other lines create off-center or more complex shapes.

As students compare these effects, they build intuition about how geometric transformations impact accumulated volume.

Process for Comparing Different Lines of Revolution

Steps to Analyze and Contrast

Students can systematically compare axes of revolution by following these steps:

Identify the orientation of the axis (horizontal or vertical).

Determine the correct distance expression from the function to the axis.

Express the radius function using appropriate variables.

Set up the disc integral by squaring the radius and multiplying by .

Compare resulting integrals to observe how the change in axis affects the structure and magnitude of the volume.

Interpret how geometric differences influence the overall solid.

This process strengthens understanding of the relationship between geometry and integration, helping students form accurate disc method integrals regardless of the axis chosen.

FAQ

Two solids may have the same volume if the radius functions differ in form but produce the same squared expression after simplification.

For example, shifting the axis in one direction may enlarge radii while a different shift decreases the interval over which they are integrated, balancing the accumulated volume.

You can check this by:

• Comparing the simplified integrands directly.

• Checking whether a substitution aligns one integral with another.

• Confirming both regions and radii generate equivalent accumulated areas.

When the axis is vertical, radii must be horizontal distances, which depend on x-values. If a function is given as y in terms of x, this is already suitable.

But when revolving around a horizontal line, radii depend on y-values.

If the function is not easily inverted, you may need to write x in terms of y so that distances are measured correctly along the vertical direction.

Common pitfalls include:

• Forgetting to take the absolute distance between the curve and the axis.

• Using the function instead of the coordinate of the axis, leading to reversed or negative radii.

• Overlooking that the radius changes sign if the curve lies on the opposite side of the axis, even though distance must remain positive.

A reliable strategy is to write radius as “top minus axis” or “axis minus function”, depending on orientation.

A vertical axis often suggests integrating with respect to y, because disc slices become horizontal and radii are more naturally expressed from left to right.

A horizontal axis often favours integrating with respect to x for similar reasons.

Choosing the simpler variable often reduces:

• The need for inversion.

• Piecewise cases where the region changes shape.

• Algebraic complexity in the radius expression.

Yes, in some cases shifting the axis may make the disc method more suitable than the washer method, or vice versa.

For example:

• If shifting the axis removes a hole in the solid, washers reduce to discs.

• If shifting creates a gap between the region and the new axis, discs must become washers to account for inner and outer radii.

recognising this early saves time and prevents setting up an incorrect integral.

Practice Questions

A region in the first quadrant is bounded above by the curve y = 4 − x and below by the x-axis on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 4. This region is revolved about the line y = −1.

Find the expression for the radius of a typical disc used to compute the volume of the resulting solid of revolution.

(1–3 marks)

Mark Scheme

• 1 mark: Correct identification of radius as distance between the curve and the line y = −1.

• 1 mark: Correct expression: radius = (4 − x) − (−1) or radius = 5 − x.

Maximum 2 marks.

Let R be the region bounded by y = x, y = 0, and x = 2.

(a) Write a definite integral using the disc method for the volume of the solid formed when R is revolved about the y-axis.

(b) Write a definite integral for the volume of the solid formed when the same region R is revolved about the vertical line x = 3.

(c) Explain how the change in the line of revolution affects the radius function and the overall structure of the integral.

(4–6 marks)

Mark Scheme

(a)

• 1 mark: Recognises radius is horizontal distance from curve to y-axis.

• 1 mark: Correct integral: V = ∫ from 0 to 2 of π(x)² dx.

Maximum 2 marks.

(b)

• 1 mark: Identifies radius as the distance between x and 3.

• 1 mark: Correct integral: V = ∫ from 0 to 2 of π(3 − x)² dx.

Maximum 2 marks.

(c)

• 1 mark: States that shifting the axis changes the radius function by adding or subtracting a constant.

• 1 mark: Explains that because the radius is squared, the structure and magnitude of the integral (and therefore the volume) change accordingly.

Maximum 2 marks.

Overall maximum for Question 2: 6 marks.